This post has been updated on Friday July 29th

An official statement on the homepage of the theater, posted on January 11th, announced that Iwanami Hall, a pioneer space for independent cinema in Tokyo, will cease its activity at the end of July 2022. The decision was apparently caused by the decrease in attendance due to the ongoing pandemic. It’s was shocking news that reverberated not only in Japan, a sad day for cinema culture in the archipelago, and definitely an event that signals an end of an era. There are different angles from which this news can be approached and discussed, for instance, putting it in the broader context of the changing shape of cinema, or analyzing the closure in connection to the current film exhibition and distribution landscape in Japan and beyond. What I would like to do here today though, is to seize this unfortunate chance to celebrate Iwanami Hall and everything that the space and the people involved with it have meant for cinema culture in Japan in the last half century, focusing in particular on the Japanese films and documentaries screened.

Considered by many experts the trailblazer of what would become the Japanese mini-theater boom of the 80s—that is, the proliferation of small independent venues where movies made out of the big studio system were screened—the idea of a space dedicated to the performing arts and cinema was born at the end of the 1960s, when Iwanami Yujirō, then president of Iwanami Shoten, one of Japan’s largest publishing companies that later spun also into the documentary world with the glorious Iwanami Production, decided to have a separate building made for the visual arts, the Iwanami Jimbochō Building. It is inside of this new construction that Iwanami Hall was established and found its place in February 1968, at first as a multifunctional center dedicated to various arts, and in 1974, with the formation of Equipe de Cinema, a group curating and distributing films, as a proper cinema theater capable of accommodating about 200 customers.

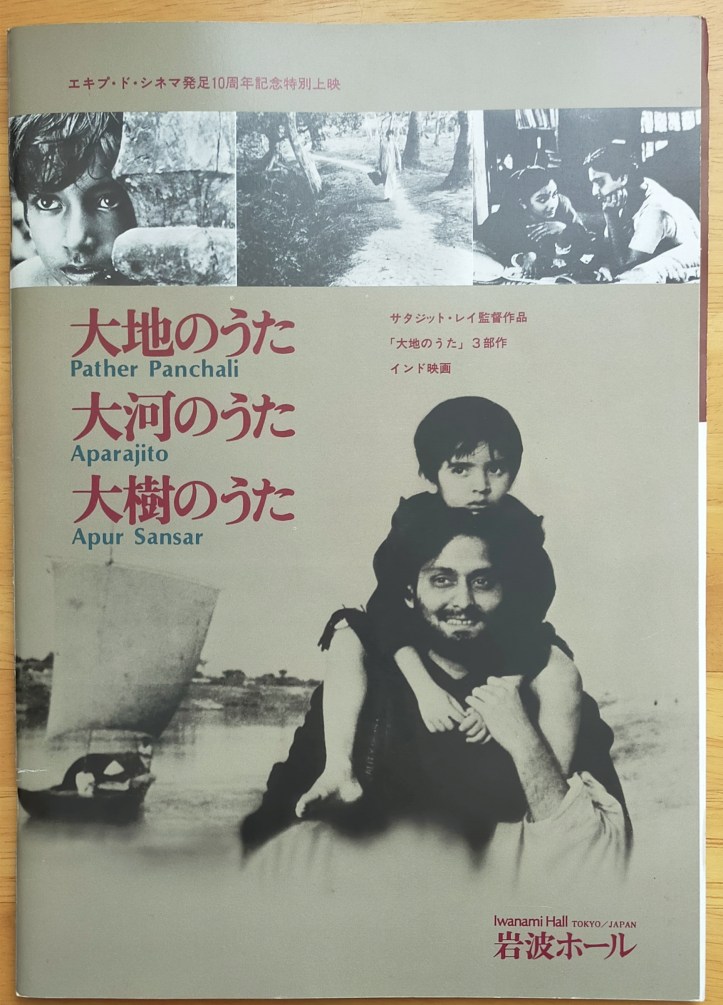

A pivotal figure for the activities that would be carried out in the following decades in the theater through the group was Takano Etsuko, who had previously worked in distribution for Toho, and who would serve as the director of the theater until her death in 2013. The philosophy that has guided the cinema since its beginnings is a special focus on films from areas less covered by traditional Japanese distribution, such as Latin America, Asia and Africa. In this sense, the first movie screened at the cinema, in February 1974, Satyajit Ray’s The World of Apu, felt like a mission statement.

Four were the guiding principles behind the activities of Iwanami Hall and Equipe de Cinema:

- Introducing masterpieces from non-Western countries such as Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and also focusing on feature films directed by women.

- Screening of non-Japanese films that usually are not picked up by major distribution companies.

- Showing important film in the history of cinema, that are not screened in Japan for some specific reasons, and films that have been cut or shown in incomplete form.

- Introducing significant Japanese films to the world

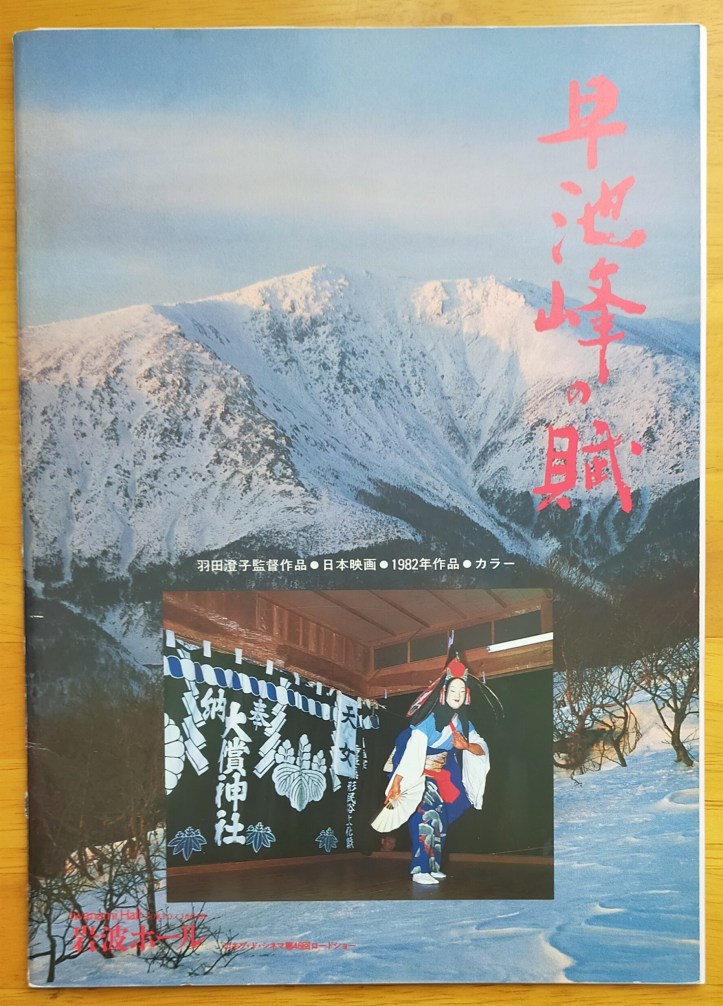

As written above, one of the goals of Equipe de Cinema and Iwanami Hall was to introduce and show art house cinema from all over the world to the Japanese viewers, and thus in the first decade of its existence the cinema focused mainly on non-Japanese films. However, there were some notable exceptions, Gassan (1979, Murano Tetsutarō) was made to celebrate the fifth anniversary of Equipe de Cinema and was screened at Iwanami Hall from October 20 to December 4, 1979. Children Drawing Rainbows (1980) by Miyagi Mariko, an actress and activist whose life would deserve an in-depth piece, a documentary about children with disabilities, was screened from July 26 to September 5, 1980, and Ode to Mt. Hayachine (Haneda Sumiko), from May 29 to June 25, 1982, and again, due to its success, August 7-13.

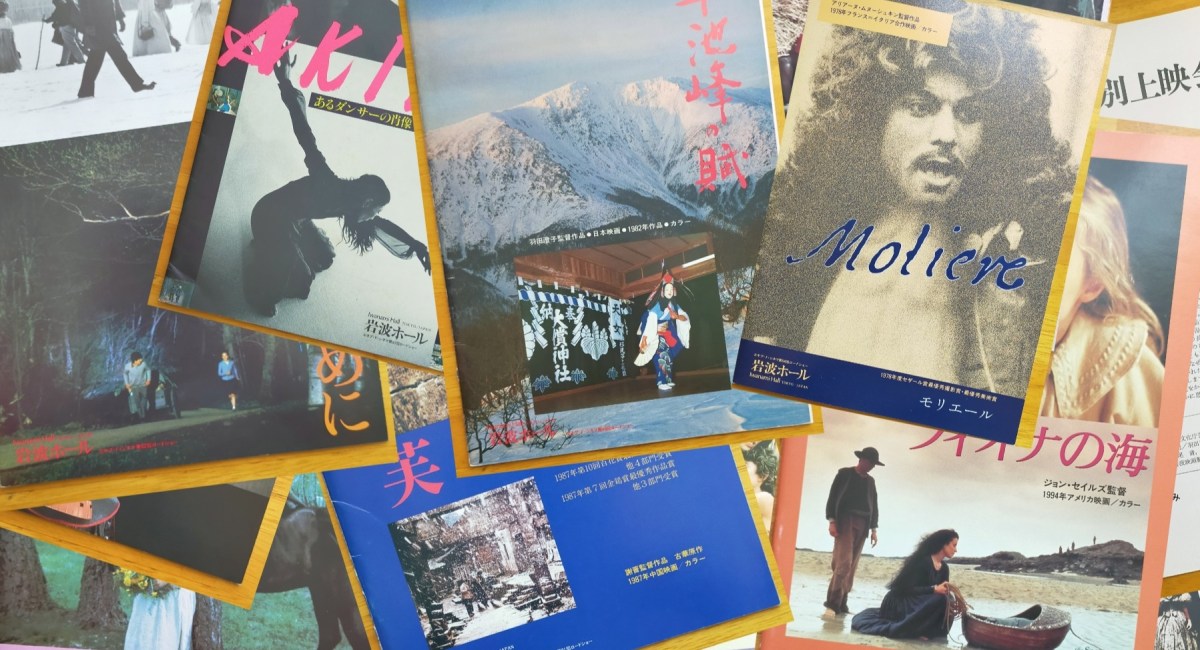

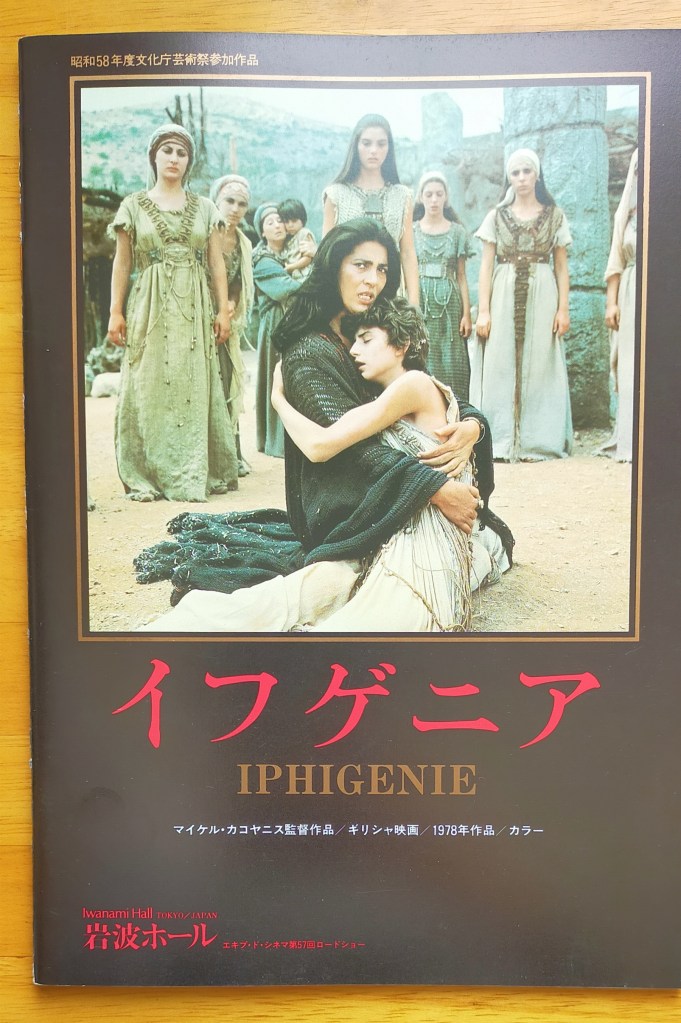

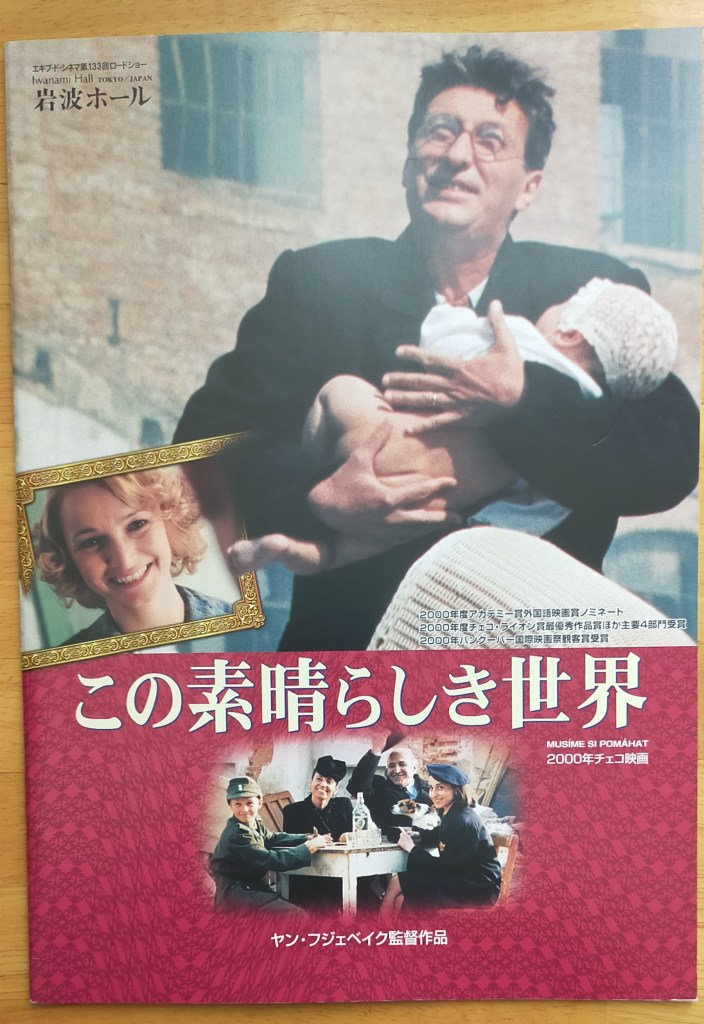

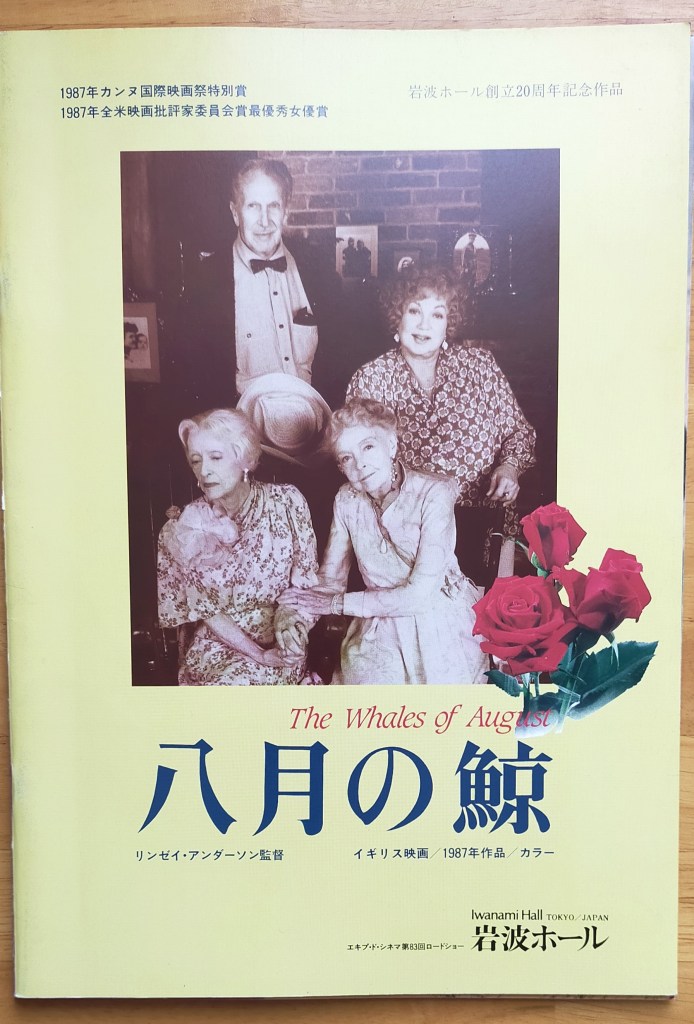

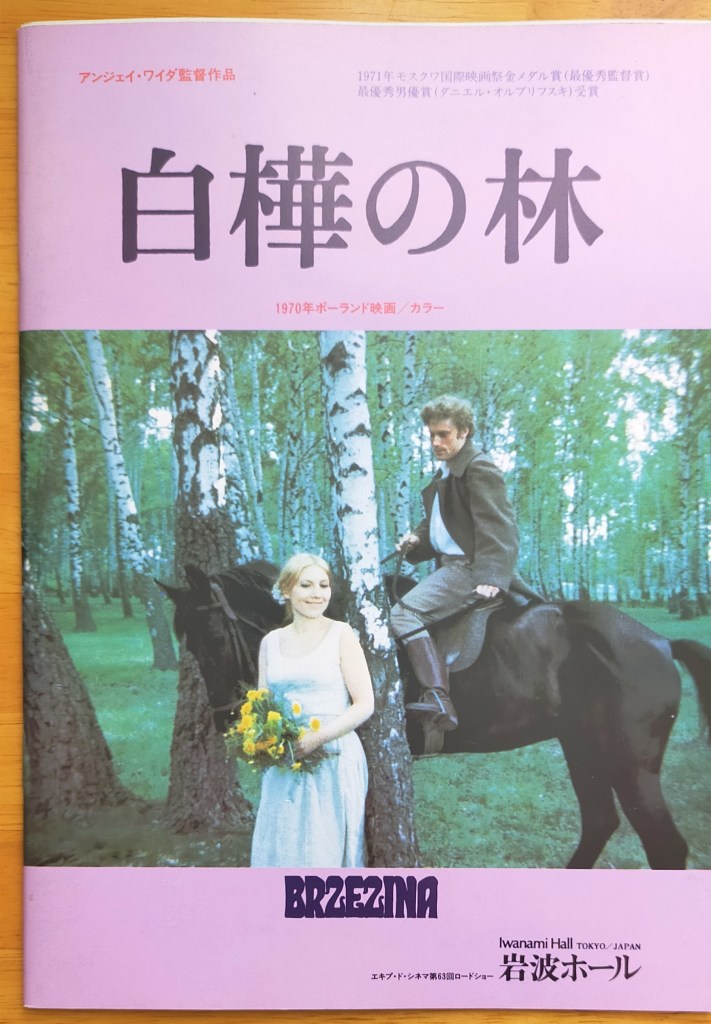

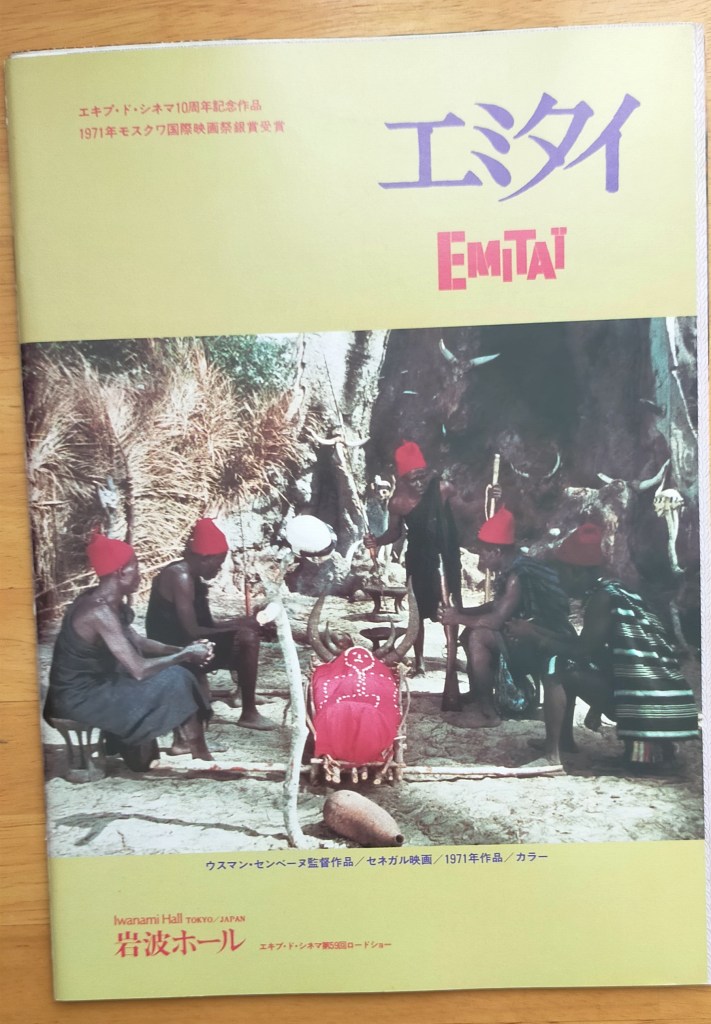

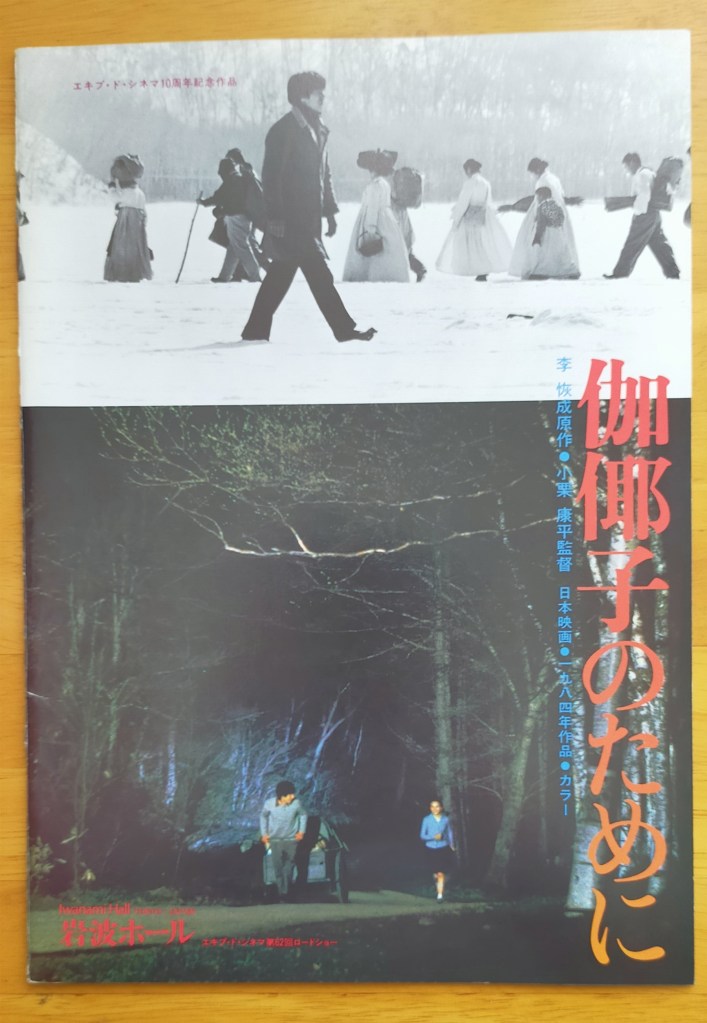

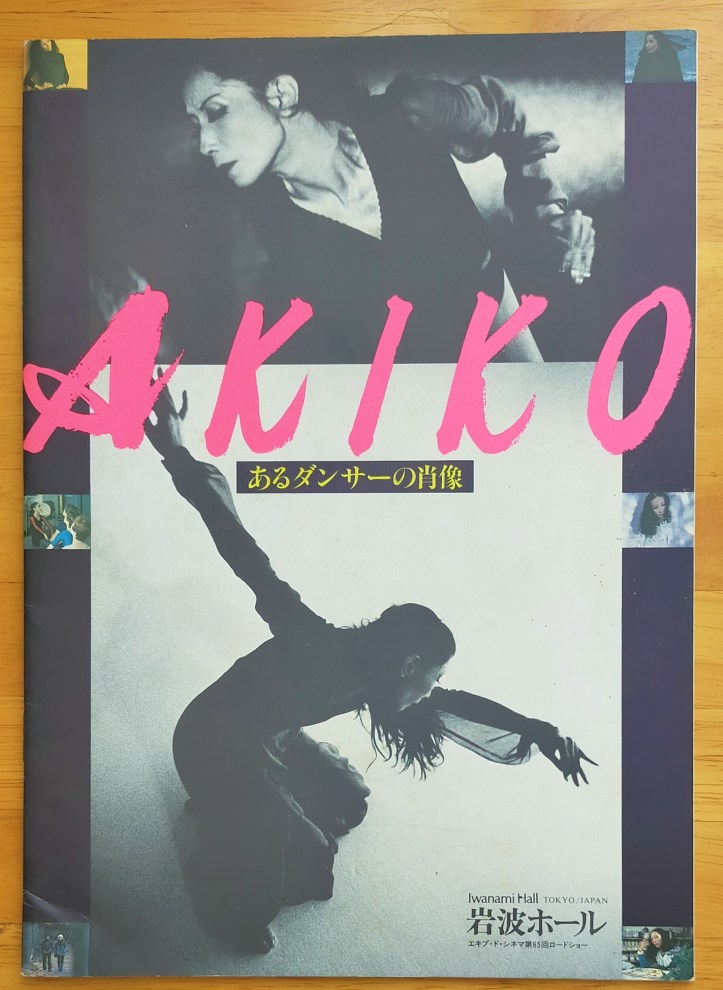

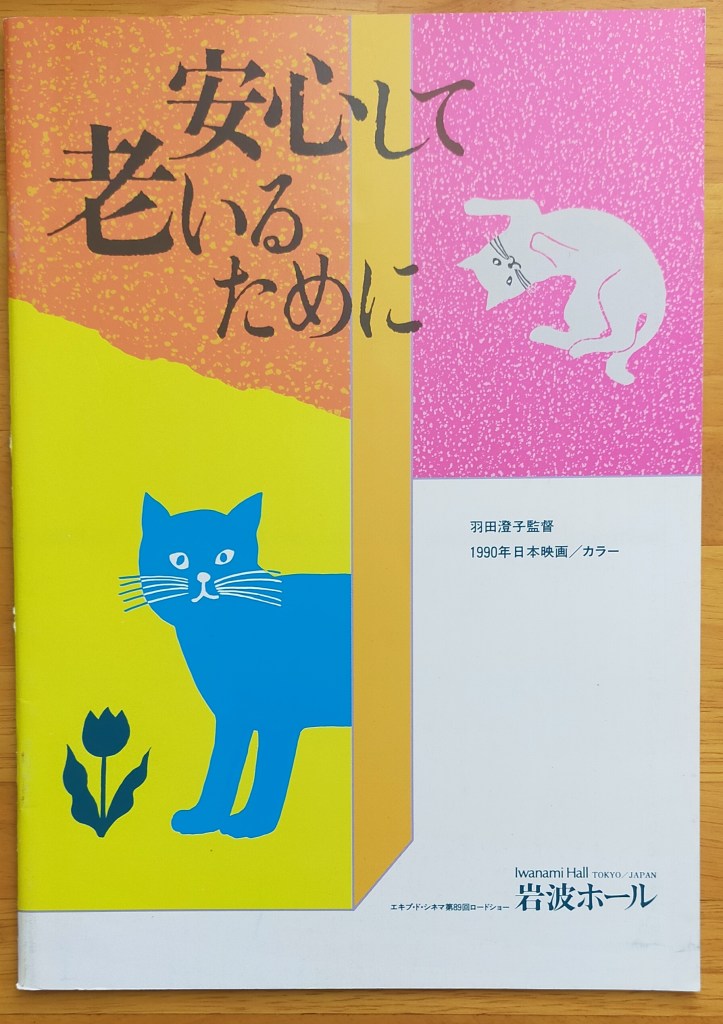

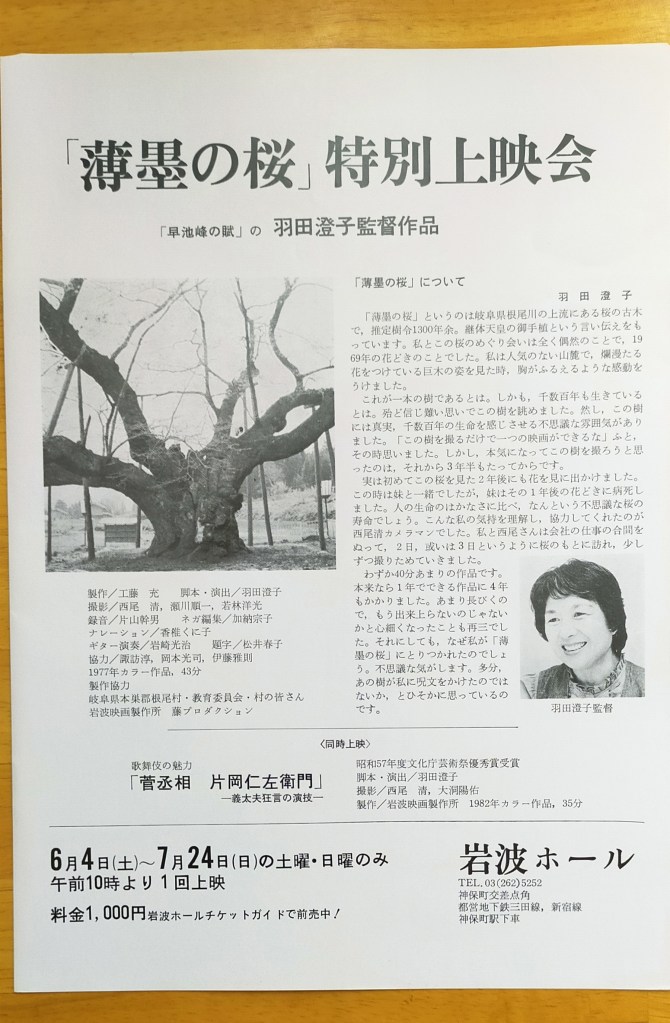

In the slideshow below you can find some of the booklets produced by Equipe de Cinema for the movies screened at Iwanami Hall in the last 50 years, not simple leaflets, but in-depth analysis of the film in question with contributions from scholars, critics and directors themselves (right click to swipe):

This is the last message from Iwanami Hall’s manager, Iwanami Ritsuko, posted on YouTube on July 28th:

The message summaries the birth and activities of Iwanami Hall during the last half century, stressing its importance in bringing and showing to Japanese audiences films from different parts of the world in a time when only big American and European productions were screened.

What is interesting for us here, is that during the so called boom of mini-theaters in Japan (from the mid 1980s onwards), Iwanami Hall, while continuing the screening of international cinema, focused its attention also on a different type of Japanese cinema, one that dealt with the problems of an aging society, people with disabilities, and one made by women directors.

This last point is a crucial one, because for more than 50 years Iwanami Hall has been functioning as an unofficial hub for woman in cinema, not only screening cinema made by female directors, but also involving women in the activities of the group and theater. The premium example of this is, as Iwanami Ritsuko says in her message, Nakano Etsuko. She really wanted to became a director, but it was almost impossible at the time, and that’s why she decided to go to France to study. Once back in Japan she tried again, writing scripts for TV, but the society of the time was still too male-centric. After working for Tōhō, Nakano found her place in Japanese cinema when she established Equipe de Cinema and became manager of Iwanami Hall.

The case of Ode to Mt. Hayachine

From the spring of 1979 and for about 16 months, Haneda Sumiko and her cameramen visited several times the villages of Dake and Ōtsugunai, in Iwate prefecture, to shoot Hayachine Kagura, a sacred dance performed in the area for centuries, and the lives of the people in the villages. After the shooting was completed, Haneda with her husband Kudō Mitsuru as a producer, made 早池峰神楽の里 Hayachine kagura no sato, a independent documentary that later was backed by Iwanami Production. The 52-minute work, made with the financial support of the villages, did not satisfied Haneda though, who thought that the subject and the people of the area needed a longer treatment. Up to that time Haneda had made only relatively short documentaries, and 薄墨の桜 The Cherry Tree with Gray Blossoms, her first independent documentary (1977), a work that kicked off her career as an independent documentarian, was only 42′ long.

However, this time she felt the need for a different length in order to put in images what she experienced in Iwate. Gathering all the footage shot, Haneda ended up making 早池峰の神楽 Hayachine no kagura, a documentary 195′ long, a work she assembled just for the people of the villages and for herself, as a document to preserve the ancient art of kagura and a way of living that was quickly disappearing.

In 1981 she screened the movie in one of the villages, just a private screening held at a community hall. It was a success, and the people of the towns saw it several times. Haneda was particularly enthusiastic to hear that the women of the villages were finally able to properly see the festival and the kagura dance, since during the main festival they were usually so busy cooking, preparing and organizing everything, that they didn’t usually have time to see the kagura or enjoy the festival. Once she was back in Tokyo, Haneda showed the movie to Kawakita Kashiko and Takano Etsuko, at the time the leaders of Equipe de Cinema. They were so impressed by Hayachine no kagura, that they offered Haneda the possibility of having it screened at Iwanami Hall. She reluctantly accepted, but the film was still too long, and so it was decided to shorten it of 10 minutes. The final result was titled 早池峰の賦 Ode to Mt. Hayachine (185′), and was screened at Iwanami Hall starting from the Golden Week of 1982 (May). The documentary was screened for several weeks and was praised by viewers and critics alike.

The movie and the screenings held at Iwanami Hall were a turning point in Haneda’s career, who, from that point on, decided to quit Iwanami Production and pursue, together with her husband, a path in independent documentary cinema. The documentaries she made in the last part of her career were almost all screened at the theater.

Had not been for Takano, Kawakita, Equipe du Cinema, and the chance offered her by the screening at Iwanami Hall, the documentary would probably have never been shown to the public and stayed in a box, forgotten, and Haneda’s career would have taken a different direction.

This is just one specific example, among many, illustrating the importance Iwanami Hall played for cinema culture in Japan.

One thought on “Iwanami Hall 1968 – 2022, a celebration”