Today I’m posting a translation of my piece on gentō (magic lanterns) and mine protests originally published in 2019 in Italian on Alias (Saturday supplement of Il Manifesto)

In December 1959, Mitsui, one of Japan’s largest zaibatsu, announced the imminent dismissal of 1,278 coal miners in Miike, southern Japan, as part of a restructuring of the nation’s energy policies. The response was massive. Over 1959–60, the workers first formed a new union and then launched a series of strikes and protests—among the largest the country had ever seen.

The protests and uprisings that shook Japan in the late 1960s—against the construction of the Narita Airport, in Okinawa, and in the streets merging with student movements—have been widely documented in both fiction and non-fiction films, as well as in written form. By contrast, labor and resistance movements of the previous decade remain a far less familiar chapter, both in Japan and abroad.

One important exception is perhaps Kamei Fumio’s 1955–56 trilogy on the resistance against the U.S. base at Sunagawa—protests that achieved tangible victories and, on a cinematic level, anticipated the documentary practices of Ogawa Production in later decades.

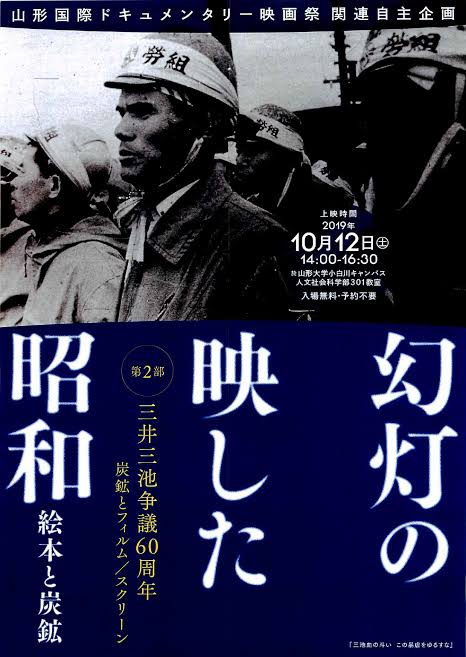

At the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival 2019, a satellite event held outside the usual venues on October 12 revisited this earlier period, with special screenings devoted to gentō and the grassroots movements that flourished in the 1950s. The spirit and strategies of resistance against capital and corporate power that emerged on the international stage in the 1960s cannot be fully understood without first recognizing the protests and class alliances forged in the preceding decade.

Gentō—literally “magic lantern”—was a technology that had enjoyed wide popularity in the late 19th century before being displaced by cinema, yet in Japan it experienced a surprising revival during the 1950s. Essentially an early form of the slideshow, gentō projections combined a sequence of still images with live narration and, often, music. This seemingly “obsolete” medium was repurposed by labor collectives, Okinawan anti-occupation activists, students, and citizens engaged in a variety of struggles, since it was cheaper and more accessible than cinema at a time when portable film formats were not yet widespread in the archipelago. These performances thus became a powerful means of circulating experiences of resistance, while also resonating with deep-rooted cultural traditions.

The three gentō screenings shown in Yamagata, introduced and performed by professors Washitani Hani and Toba Koji, evoked the atmosphere of Japanese silent cinema, when more often than not, a benshi live narration would shape the tone and meaning of the film. They also recalled kamishibai, the popular paper-theater storytelling format for children, long familiar across Japan.

Underground Rage, the first piece, dates to 1954—before the major strikes—but already captured the mounting tensions between management and miners. It recounts the “113 Days Without Heroes” of 1953, a protest against layoffs that involved workers and their families. “We are not Mitsui’s slaves!” “The company wants to kill us!”—these slogans framed a furious indictment of exploitation, aiming to forge a class consciousness that reached beyond Miike to farmers and other workers across the archipelago.

The second work, Bloody Battle in Miike: Never Forgive These Atrocities, is perhaps the most emblematic. It documents a massive demonstration in March 1960 outside Mitsui’s offices where not only did the police intervene, but the yakuza were called in to suppress the protest. Photographs show about 200 gangsters from two different syndicates surrounding workers with clubs and other weapons. One even brandishes an axe, believed to have been used in the killing of protester Kubo Kiyoshi, who was brutally murdered on March 29, 1960.

The third work, Unemployment and Rationalization: Never Put Out the Fire of Botayama (1959), examines the looming mine closures and, more broadly, the operating methods of the zaibatsu—the powerful capitalist conglomerates—and their impact on miners’ families, particularly women and children. It depicts homes reduced to shacks without electricity, chronic food shortages, and malnourished children forced to survive on a single meal a day. It is a bleak portrait that echoes across eras and geographies, whenever the capitalist machine consumes the vulnerable and consigns the “expendable” to sacrifice.

The Miike mines would return to the headlines in tragedy in 1963, when an explosion killed nearly 500 people and poisoned thousands, and again in 1997 with another fatal accident that led to their final closure. These gentō shows serve both as invaluable records—produced from within—of a vanished era, and as proof that an “outdated” technology, when adapted to a cause and a moment, can become powerfully expressive, effective, and even modern.