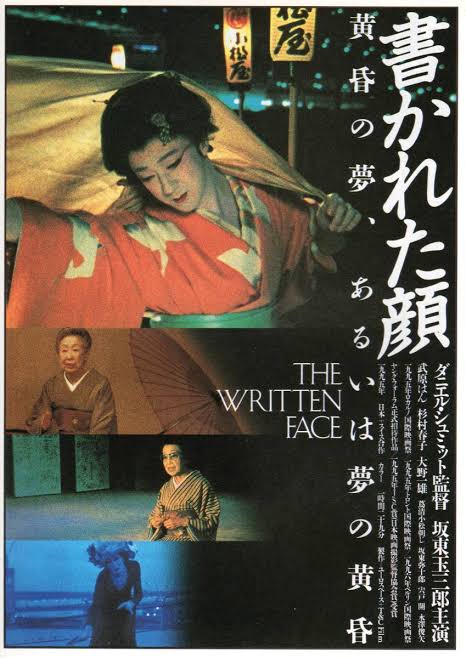

Presented in its 4K restored version last summer at the Locarno Festival, 書かれた顔 The Written Face (1995) offers a fascinating and at times experimental portrait of Bandō Tamasaburō, kabuki actor known in Japan especially for being one of the most talented onnagata ever, a man who plays the role of a woman in traditional Japanese theatre. Bandō has also directed a couple of movies, and appeared as an actor in a number of films, among which I would like to highlight at least 夜叉ヶ池 Demon Pond (1979), an excellent movie by Shinoda Masahiro, with an outstanding performance by Bandō in the double role of a girl and a mythical princess.

The Written Face is a Japanese-Swiss coproduction directed by Swiss filmmaker Daniel Schmid, who assembled together Bandō’s on-stage performances, which make up the bulk of the film, with interviews of artists he was inspired by, such as actress Sugimura Haruko, the face of many works by Ozu and Naruse, dancer Takehara Han, the elderly geisha Tsutakiyokomatsu Asaji, and Ohno Kazuo, the great butoh dancer, subject of another movie directed by Schmid and also released in the same year, Kazuo Ohno (1995). The movie is also punctuated by short interviews with Bandō himself, and wrapped up with a film within a film, Twilight Geisha Story, a short movie without spoken words starring the actor himself in the role of a geisha at the end of her career.

The Written Face opens with Bandō on stage, his performance, however, is filmed from the side and not frontally as seen by the audience. These scenes are alternated with brief passages in which the actor strolls through the streets, or explores the stage and the areas surrounding it, as if he were watching the performance he himself is acting in. Once the show is over, after the roaring applause of the off-camera audience, the film shows Bandō removing his make-up, the white patina covering the face, the wig, the heavy dress, and profusely thanking the musicians. At this point we cut to the actor in plain clothes chatting with a child, probably his young son, who is playing with a portable video game. While the scene itself is very brief and not too significant in itself, when considered in the context of the movie, so far made mainly of acting on stage, ritual gestures and traditional music, it represents a counterpoint that zooms us out of the stage performances, and anchors the film to the time it was filmed, the 1990s. While most of the movie, as written above, is made by the beautifully choreographed performances of Bandō, everything else that surrounds them— interviews, words, and “pillow shots”— functions as an indirect explanation of his artistic approach, and partly as a deconstruction of what is happening on stage. One of the crucial points of the movie is when we first hear Bandō’s voice reflecting on his art and approach. He is sitting in a hotel facing what is probably Osaka Castle at sunset, and explaining to the interviewer what he is trying to express when he takes the stage as onnagata: “I do not represent a woman, but I suggest the essence of women. That is the nature of the onnagata, isn’t?”.

In order to do so, Bandō has often seeked inspiration, throughout his career, from the art of the four aforementioned figures, each of them representing a different and unique type of femininity. A clip from Naruse Mikio’s 晩菊 Late Chrysanthemums (1954) suggests the particular type of femininity, strong and direct, Sugimura often represented in her long and glorious film career. At the other end of the spectrum, the dancing body of Ohno, 88 years old at the time, immersed in the blue of dawn, and surrounded by water, captures and expresses something more ethereal and dreamlike. Ingrained in the nihon-buyō‘s tradition are the dance movements that Takehara performs for the film, delicate, elegant, and almost imperceptible, while the voice of Tsutakiyokomatsu, trembling but still full of life, is a sign of a fierce vitality, she was 101 years old at the time of the shooting.

After the short Twilight Geisha Story, a segment about twenty minutes long, which perhaps represents the weakest part of the work, in the last ten minutes, the movie returns to a kabuki play with Bandō protagonist. The performance is Sagi Musume (1762), also the opening performance of the documentary, one of the most famous and celebrated kabuki play in Japan. It is the story of a girl, abandoned by her lover, who is transformed into a heron and dies on a snowy night. Bandō’s performance is here breathtaking in its beauty.