This short article could be considered an addendum to the piece I wrote several months ago about found footage films, compilation documentary and recycled cinema in Japan.

When Collaborative Cataloging Japan, the online platform dedicated to experimental and avant-garde cinema in the archipelago, made available Doi Haruka’s He Was Here, and You Are Here (なかのあなた いまのあなた 1985) a couple of years ago, it was for me a revelation.

The short film is an impressive and poetic debut centered on the idea of externalising one’s own memories, wishes, and fantasies as images projected onto walls, plates, or even the filmmaker’s own body. He Was Here, and You Are Here crystallizes the inventiveness of a particular approach to personal cinema in Japan during the 1990s, while at the same time standing as an exception—a singular and highly idiosyncratic experiment within the realm of Japanese “self-documentary” of that period.

For the whole month of December 2025, another work by Doi, My Father, burned (父が、燃えた 1994), is available to stream on the platform.

While He Was Here, and You Are Here marked Doi’s debut, My Father, burned represents her final foray into filmmaking, a career that lasted less than a decade. In the following years, Doi has been active in the field of Japanese music under the pseudonym HALUKA.

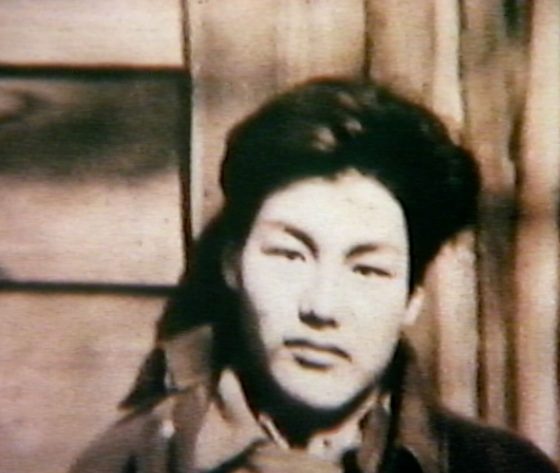

The short film originated in Doi’s discovery of old photographs of her father, along with home movies he had shot himself. As Collaborative Cataloging Japan notes, My Father, burned—described by the filmmaker as an “anti–home movie” —is a rare example of personal film that

illustrates Doi’s complicated relationship with her deceased father. A distanced fascination replaces the nostalgic or sentimental aspects one might expect in a film of this kind. Yet the sense of the power of the found image to shock and disarm remains — the familiar face that stares out from the rediscovered album; the laughter of a past self, seen through the eyes of one deceased. Through this cinematic reflection, Doi questions the image she had of her father prior to this posthumous mediation, even seeing similarities between his violent tendencies and her own rebellious nature.

The film is not only a reflection on Doi’s difficult relationship with her father after his passing, and on how memories shape who we are and who we become, but also a more subtle contemplation of the latent potential inherent in the reactivation of audiovisual footage—here, personal material.

Home movies shot by her father when she was little, together with old photographs of him, resurrect the “shadow” of his physical body, helping to construct a different image of the man and an alternative personal reality once inhabited by the filmmaker. Doi’s efforts here, albeit on a smaller and more personal scale, mirror those at work in the best examples of archival or found footage cinema, which “draw on archival material to breathe new life into it and construct new constellations of meaning—capable of questioning the present through a reconfiguration of the past.” (Cau, 2023)

My Father, burned represents thus a prime—if rare—example of the convergence of personal and archival cinema in Japan during the 1990s. This is particularly evident not only from what has been described above, but also from the film’s formal structure, in which the filmmaker’s thoughts are articulated as a form of commentary or narration accompanying the old photographs and home movies presented on screen.

It is also fascinating that the filmmaker briefly reflects, toward the end of the work, on the ethics of filming a dying person—when her father was ill in the hospital. Although this comment is not further developed, it remains a very relevant topic today and sheds light on Doi’s talent and her acute awareness of everything that surrounds the act of filming and filmmaking itself.

References:

Maurizio Cau, Rifigurare il passato. Il cinema d’archivio di Sergei Loznitsa in “Cinema e Storia 2023. Found footage: il cinema, i media, l’archivio” edited by Alberto Brodesco and Maurizio Cau, Rubettino edizioni, 2023.