On March 20, 1995—the day sarin nerve gas was released in several cars of the Tokyo subway—Japan experienced what is often regarded, together with the Great Hanshin earthquake two months earlier, a watershed moment in the recent history of the archipelago. Much has already been written and said about the attack carried out by members of the Aum Shinrikyō cult, which killed 13 people and injured hundreds, about the motivations behind it, and about the figure of Asahara Shōkō, the group’s leader, who was eventually executed in July 2018. Within documentary cinema, it is worth recalling at least Mori Tatsuya’s A (1998) and A2 (2001), two key works exploring the sect’s inner workings after Asahara’s arrest and its relationship with the mass media.

Far less attention, however, has been paid to Asahara’s family and to how the tragedy that unfolded three decades ago also affected his closest relatives. Most of them, understandably, changed their names and had their identities protected—especially the children, who were still minors at the time. The sole exception is Matsumoto Rika, Asahara’s third daughter (his real name being Matsumoto Chizuo), who was twelve years old at the time of the attack and had been designated as her father’s spiritual successor. A few years ago, she chose to reclaim her real name, come forward publicly, and stop hiding.

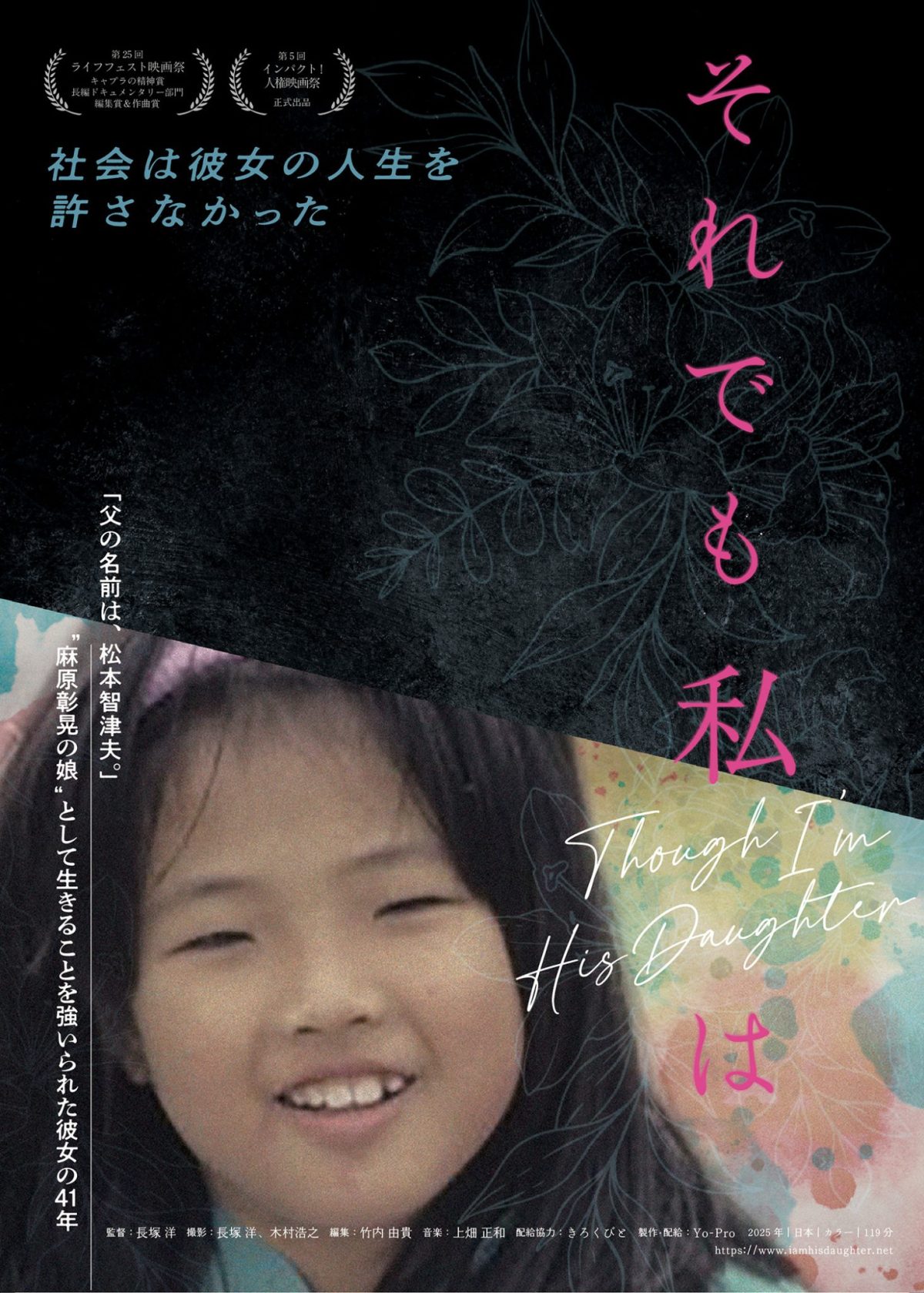

Though I’m His Daughter, a documentary directed by Nagatsuka Yō and released in Japan last year, investigates the reasons behind this decision and follows Rika’s life over a period of roughly six years, from 2018 to 2024. Although the film was screened in a limited number of cinemas across the archipelago last year, it appears to have maintained a relatively low profile, as addressing Aum Shinrikyō and its members remains a delicate and problematic subject—both for the Japanese state and for public opinion, which often, and rightly, calls for respect toward the victims of the attack.

Significantly, the film opens with a meeting between Rika and the brother of one of the victims of a manslaughter case that occurred in Aichi prefecture in 1979 (the so called Handa Hoken Kinsatsujin Jiken)—an encounter initiated by the latter—which immediately sets the film’s thematic tone. One of the documentary’s central concerns is precisely the way in which the relatives of victims and those of perpetrators come to share—to different degrees, naturally—a common fate: that of carrying an almost unbearable burden for the rest of their lives.

Yet the theme that perhaps emerges most forcefully from the film is the complex and deeply ambivalent relationship between father and daughter. While unequivocally condemning her father’s actions, Rika is shown to retain many positive personal memories of him. She cannot make sense of how the violence carried out by the group could coexist with one of its central tenets—the prohibition against killing, even insects. Moreover, following his arrest, she was never able to speak with him or ask about the true motivations behind his actions—both because officials did not permit such a meeting and because Asahara is said to have descended into a state of mental confusion after his arrest, to the point that he was reportedly no longer able to speak coherent Japanese. The film also shows briefly Tatsuya Mori, director of the aforementioned A and A2, attending a meeting held prior to Asahara’s execution in support of granting him proper medical treatment, so that it might be determined whether he was truly the one who ordered the killings—and why—two of the most significant unresolved questions hanging over both the film and Japanese society.

Rika learned of her father’s execution from a friend who was watching the news on television. At that moment, the director was understandably unable to film her; instead, Rika recorded herself, along with her sister Umi—whose identity is protected by the blurring of her face. The resulting footage shows her sister having an emotional breakdown while riding on a bus or in a car.

The emotional ambivalence towards his father is compounded by the discrimination Rika continues to face as she attempts to navigate Japanese society. Following the execution, Rika became the target of a wave of online harassment, with social media flooded by death threats and messages directing rage toward her. In this section of the film, screenshots of tweets and replies appear on screen, one of which starkly encapsulates the situation: “you have no right to be happy.” Finding employment, opening a bank account, or sustaining a romantic relationship all prove to be nearly insurmountable challenges. As a result, Rika experiences recurring bouts of depression and suicidal thoughts; here again, video footage—this time shot by her sister Umi—is used.

The death wish Rika harbored as a teenager after her father’s arrest—she remained in the group for four years following the attacks—painfully resurfaces. Her memories of that period are rendered on screen through harrowing sequences depicted in pencil animation.

As a way of confronting and reconnecting with their past, Umi and Rika travel to their father’s hometown, where his family once ran a tatami shop, reminiscing about a time when they still saw him as a caring figure. During the same trip, they also visit relatives who had disowned them and completely severed ties with the Matsumoto family.

It is at this point in the film that Nagatsuka decides to ask Rika what he considers the most important question: “Why did such a happy and fulfilled person come to do those horrible things?” The question remains unanswered, as no one is able to make sense of what happened in his life.

The final thirty minutes of the film focus on Rika’s efforts to break free from the depressive spiral into which she had fallen—exacerbated by the pandemic—and to forge an independent life, partly through her passion for mountaineering and bodybuilding, pursuits she approaches at a semi-professional level.

The film opens with the director’s own narration, and his voice—along with the rationale behind the making of the documentary—serves as the thread connecting the work as a whole. Nagatsuka frequently appears on screen, both during and after the pandemic, including in the inevitable Zoom split-screen sequences, a choice I found visually weak. The film is at its strongest in its first hour or so, concluding with the onset of the pandemic and the visit to Asahara’s hometown, when the editing is tighter and the images are less overtly—and cheaply—emotional. The film’s concluding shot, a drone-filmed image from the top of a mountain, exemplifies the opposite tendency and ultimately feels inappropriate.

Though I’m His Daughter may not be without faults, but it possesses the considerable merit of posing difficult and compelling questions, even for viewers who may not share its underlying premises.

One thought on “Though I’m His Daughter それでも私は (Nagatsuka Yō, 2025)”