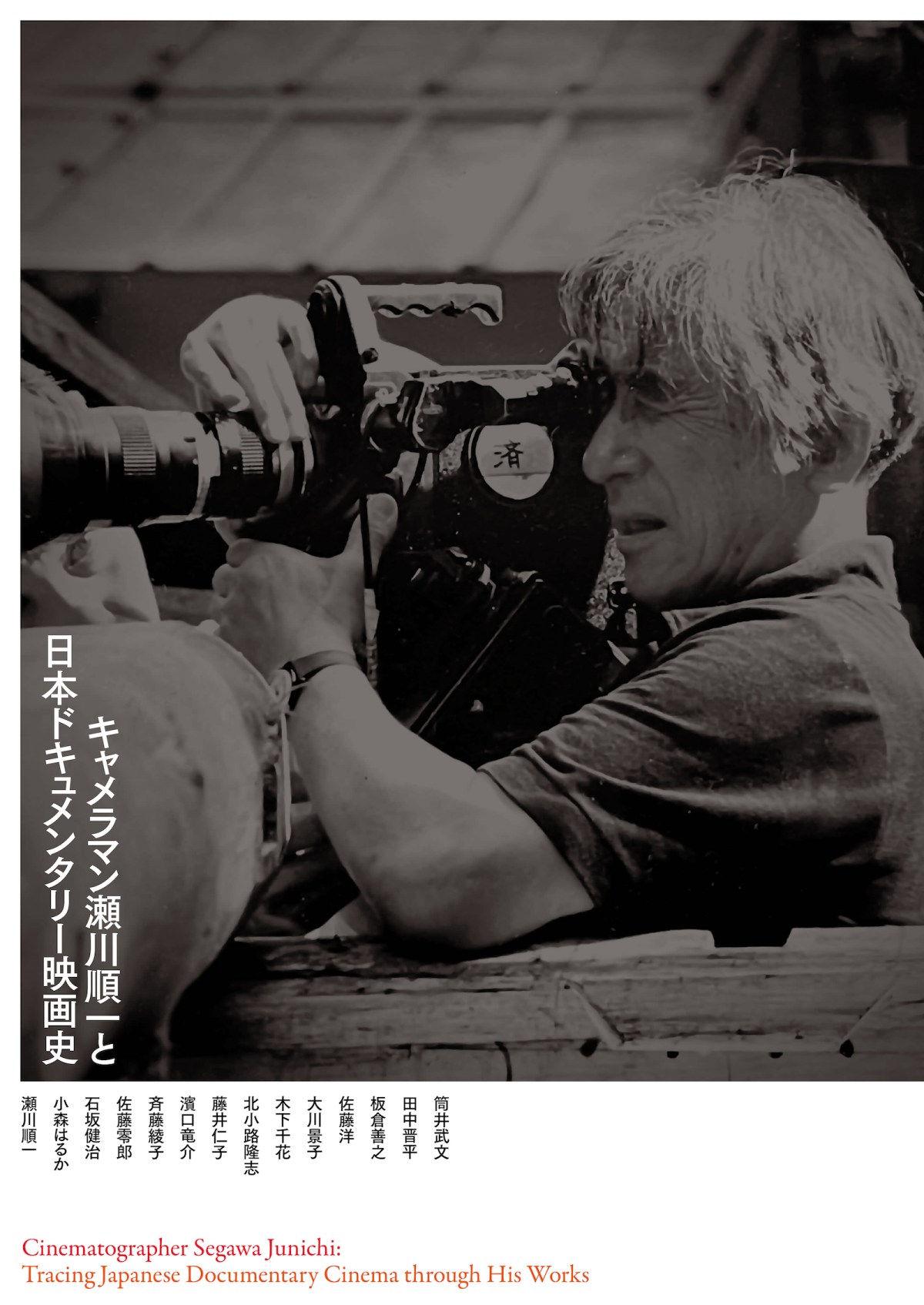

Of the many satellite events organized during last October’s Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival that I was unable to attend, one in particular caught my attention: “Cinematographer Segawa Jun’ichi: Tracing Japanese Documentary Cinema through His Works.”

This was an event organized to revisit the legacy of Segawa as a cameraman 30 years since his passing, and to kick off a retrospective that was held last December at the Athénée Français Cultural Center in Tokyo before traveling to Osaka’s Cinema Nouveau this February.

Although I had previously seen several documentaries in which Segawa worked as cinematographer, I only became fully aware of the real scope of his contribution to Japanese cinema about five years ago, while researching Haneda Sumiko’s Ode to Mt. Hayachine (1982). In Hayachine no fu (1984), her book on the film—part reflection on its genesis, part production diary—Haneda emphasizes several times the importance of having Segawa behind the camera.

In what is arguably her masterpiece, Haneda organized the shooting into two units. One group, led by Nishio Kiyoshi, focused primarily on filming the villages of Take and Ōtsugunai, while the other, lead by Segawa, concentrated on the alpine landscapes and the scenes shot near or at the summit of Mt. Hayachine, although for major sequences, such as the summer festival, the entire crew worked together. Haneda repeatedly stresses how decisive Segawa’s prior experience filming at high altitudes—and the fact that he was himself from Iwate Prefecture, where the mountain is located—proved to be for the success of the documentary.

Once I realized how central Segawa had been to the making of Ode to Mt. Hayachine, I began to look more closely at his career and discovered his involvement in several other landmark works in the history of Japanese documentary cinema such as Kamei Fumio’s Fighting Soldiers (1939) or Yanagisawa Hisao’s Children Before the Dawn (1968).

The retrospective moves precisely in this direction, offering a cartography of the evolution of Japanese nonfiction cinema, but also fiction films, through the major works in which Segawa played a key role.

24 works were screened in Tokyo and Osaka, here the list of the films in chronological order:

戦ふ兵隊 Fighting Soldiers (Kamei Fumio, 1939)

銀嶺の果て Snow Trail (Taniguchi Senkichi, 1947)

ジャコ萬と鉄 Jakoman and Tetsu (Taniguchi Senkichi, 1949)

新しい鉄 Atarashii tetsu (Ise Chōnosuke, 1956)

法隆寺 Hōryū-ji (Hani Susumu, 1958)

新しい製鉄所 Atarashī seitetsusho (Ise Chōnosuke, 1959)

留学生チュアスイリン Chua Swee Lin, Exchange Student (Tsuchimoto Noriaki, 1965)

夜明け前の子どもたち Children Before the Dawn (Yanagisawa Hisao, 1968)

仕事=重サ×距離 三菱長崎造船所からのレポート Work = Weight x Distance Report from Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipyard (Matsukawa Yasuo, 1971)

風 The Wind (Segawa Jun’ichi, 1977)

遠い一本の道 The Far Road (Hidari Sachiko, 1977)

不安な質問 Anxious Questions (Matsukawa Yasuo, 1979)

海とお月さまたち Fishing Moon (Tsuchimoto Noriaki, 1980)

水俣の図・物語 The Minamata Mural (Tsuchimoto Noriaki, 1981)

早池峰の賦 Ode to Mt. Hayachine (Haneda Sumiko, 1982)

アントニー・ガウディー Antonio Gaudì (Teshigahara Hiroshi, 1984)

奈緒ちゃん Nao-chan (Ise Shin’ichi, 1995)

ルーペ カメラマン瀬川順一の眼 Magnifying Glass: The Eyes of Photographer Jun’ichi Segawa (Ise Shin’ichi, 1997)

回想・瀬川順一 土本典昭、2003年3月13日 (Tsutsui Takefumi, 2025)

Unfortunately, I was able to spend only one day in each city, but I managed nonetheless to see or revisit some milestones of Japanese documentary cinema.

In Tokyo, I attended a screening of Ode to Mt. Hayachine. Although I had watched it multiple times for my research, this was my first experience seeing it on 16mm and in a theatrical setting—and it was a revelation. The more lyrical sequences were, as expected, awe-inspiring, yet what stayed with me most after this viewing was Haneda and her team’s remarkable ability to weave an intricate and expansive audiovisual tapestry, in which people, history, folkloric practices, economic realities, non-human forces, and the mountain itself are all delicately embroidered into an ever-changing, open-ended whole.

My day in Osaka was more densely packed, with screenings of Jakoman and Tetsu—one of the few fiction films included in the retrospective, and perhaps the most handsome Mifune Toshirō has ever looked on screen—The Minamata Mural, one of the most powerful works Tsuchimoto Noriaki directed on the Minamata disaster (I wrote more about it here), and Hani Susumu’s Hōryū-ji, which left such a deep impression on me that I decided to write about it separately. Like Hōryū-ji, Antonio Gaudí (1975)—the fourth film I saw in Osaka—engages with art, though of a different kind from the Buddhist sculpture housed at the temple in Nara. The way Segawa Jun’ichi’s camera and Teshigahara’s Hiroshi’s direction capture Gaudí’s sinuous buildings and imagination—enhanced by the music by Takemitsu Tōru—is hypnotic. For my part, the film could easily have lasted six hours.

I’m not sure whether the retrospective will travel to other Japanese cities, I suspect it will not, but I secretly hope it might eventually make its way to the Chūbu region region, where I live.

The event was planned and organized by Tsutsui Takefumi, Tanaka Shinpei, Nakamura Daigo, and Okada Hidenori, and was accompanied by an excellent catalogue (in Japanese), featuring essays by film historians, scholars, and directors — including a contribution by Hamaguchi Ryūsuke.