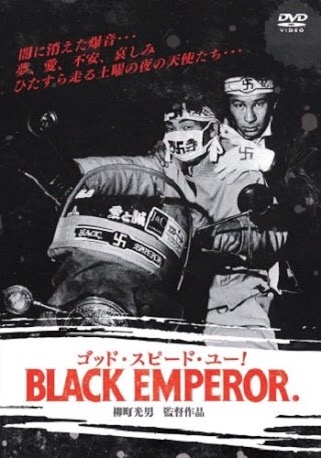

God Speed You! Black Emperor (ゴッド スピード ユー! Black Emperor) is 16mm black & white documentary by Yanagimachi Mitsuo about a group of Japanese bikers, “The Black Emperors”, part of the so-called bōsōzoku movement, the motorcycling subculture that arose during the 70s in Japan. In the following years the film became a cult movie, inspiring even a Canadian rock band that took its name from it. Now, the good news is that from September 2nd the film is again available on DVD, although only in Japan and, as far as I know, without English subtitles. If you live in Japan you can also rent the same edition, try at your local Tsutaya or Geo.

God Speed You! Black Emperor was the feature debut for Yanagimachi Mitsuo, shot after establishing his own production company, Gunro Films, 2 years before. Yanagimachi, who is known internationally also for Himatsuri (火まつり, 1985), is a director whose production during his 40 years career has been sparse to say the least, his last movie to date is Who’s Camus Anyway? (カミュなんて知らない, 2005), released exactly 10 years ago.

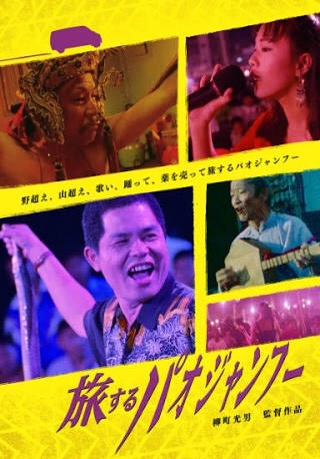

Together with God Speed You! Black Emperor the home video company Dimension (DIG) has also released other films by Yanagimachi, A 19-Year-Old’s Map (十九歳の地図, 1979), Farewell to the Land (さらば愛しき大地, 1982) and About Love, Tokyo (愛について 東京, 1992) all 3 works of fiction. A very intriguing work for me is The Wandering Peddlers (旅するパオジャンフー, 1995) his only other documentary, it premiered at the Venice Film Fest in 1995 and had never been released on home video before. I haven’t seen it, but according to Variety, Yanagimachi “and his crew went to Taiwan where they filmed, in loose cinema verité style a number of medicine peddlers, who still travel the country selling their wares and entertaining small-town audiences. Resulting pic blurs the line between documentary and fiction as Yanagimachi explores the lives of a couple of groups of peddlers, and they appear to act out their personal dramas for the camera”. The cinematographer being Tamura Masaki just adds more interest to the film.

As for the releases, as far as we know from the description, the DVDs are bare-bone editions without special features, the only extra material listed is a recent interview with Yanagimachi himself that is included in each DVD. One day it would be nice to see an edition of God Speed You! Black Emperor with English subtitles and lots of extras; putting the movie in its sociopolitical context and drawing connections with other works of the period would indeed benefit and deepen our viewing experience of it.

Links:

God Speed You! Black Emperor on DVD

A 19-Year-Old’s Map on DVD

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.