Death Education (Yuxuan Ethan Wu, 2025) is a well-shot and edited short film about how a group of young people in China think about death. The reflection is, of course, universal and is based on a program created by a high school teacher in which a class of students buries unidentified ashes in a public cemetery on Tomb Sweeping Day.

As explained at the end of the short: “Every March, Teacher Qian Jianbo holds a death education class for his students, opening up the conversation about death for the first time”.

Though the film is overly stylized in places – the slow motion of the petals scattered on a tomb was unnecessary – it succeeds in creating a somber and meditative mood that envelops the viewer. This is especially evident when images of human ashes, cremation facilities, and graves are combined with soothing music and the voices of the students reading their diary entries.

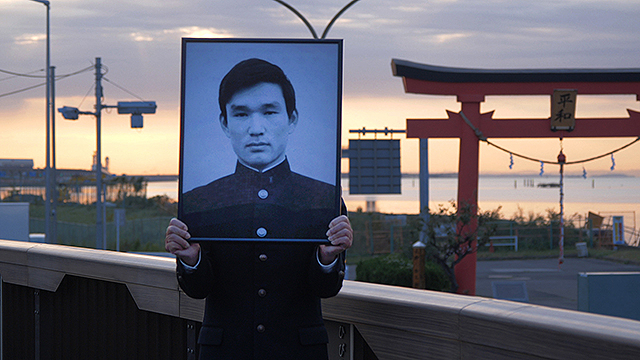

Keiko Kishi: Eternally Rebellious (Pascal-Alex Vincent, 2023) is an intriguing portrait of a Japanese cinema icon. Through interviews with the actress and film scholars, as well as home movies and clips from her most famous films directed by Ozu, Ichikawa, and Kobayashi, this French production paints a fascinating, albeit partial and incomplete, portrait of Kishi.

While the film is not particularly notable for its formal elements, I found it nonetheless interesting for several reasons. For instance, it recounts Kishi’s decision to move to France and marry director Yves Ciampi in 1957 after he filmed her as a protagonist in Typhoon Over Nagasaki. I was also surprised to learn about her involvement with the Ninjin Club, an actors’ agency founded by Kishi, Kuga Yoshiko, and Arima Ineko in 1954, that later became a production company. For two decades, the Ninjin Club produced some of the best and most boundary-pushing films of the time, including the Masaki Kobayashi Human Condition trilogy (1959–1961), Shinoda Masahiro’s Pale Flower (1964), Kinuyo Tanaka’s Love Under the Crucifix (1962), and Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964). Kwaidan is now considered a masterpiece, but it was a box-office bomb at the time, causing the company to file for bankruptcy. To pay off the debt, Kishi appeared on many TV programs in both France and Japan in the 1970s. Later in life, she shifted her career completely and started working as a photojournalist, often visiting war zones around the world.

Landscape Hunter (2021) is an experimental documentary commissioned by Chiayi Art Museum, Taiwan, and directed by Liao Hsiu-hui and the Your Bros. Filmmaking Group, a collective responsible for another fascinating experiment in nonfiction, Dorm (2021).

The film centers on Fang Ching-mian (also known as Uncle Hsin-kao), an indigenous man of the Bunun people who was a passionate amateur mountain photographer. Seventy years ago, he climbed and took photos of Mount Jade (Yu Shan), the highest mountain in Taiwan, more than a thousand times. Landscape Hunter is structured like a mosaic composed of several overlapping facets: a nonlinear, oblique, and opaque work that interweaves Uncle Hsin-kao’s shots of Yu Shan’s locations; interviews with mountaineers discussing the significance of his endeavors for the discipline; Black-and-white alpine scenery; Bunun words; and reflections on representing and capturing reality, as well as an interrogation of the absence of indigenous peoples in the history of photography.

This absence reminded me of a presentation at the last Niigata International Animation Film Festival in March. A group from the Taichung International Animation Festival concluded their showcase of animated works produced in Taiwan with a question: What is missing from Taiwan’s animation landscape? The answer is the voices of indigenous peoples.

While this is also true in the documentary field, the technological revolution brought about by video cameras and DV camcorders gave rise to a wave of indigenous-made works in the last decade of the 20th century. This was the focus of a fascinating program titled Indigenous with a Capital ‘I’ which was presented at the Taiwan International Documentary Festival in 2020. An interrogation of the relation between Photography and indigenous peoples in Taiwan is also at the center of the impressive MATA-The island’s Gaze by Cheng Li-Ming.

The self-reflexive and somewhat obscure qualities of Landscape Hunter can be traced back to the collective’s working methods and the professional backgrounds of its members. Some are video artists, some are architects, some are art history researchers, and some are theater critics. Field research, creative workshops, unforeseen circumstances, and flexible scripts are fundamental to their works and they describe their approach as “filmmaking as a method for reinterpreting reality, endowing it with an aesthetic form, and transforming it into a medium of thinking.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.