After Le Moulin, and partly Asia is One, my personal exploration of the period when Taiwan was under Japanese rule (1895 – 1945) continues today with Wansei Painter – Tetsuomi Tateishi (2015), a documentary directed by Kuo Liang-yin and Fujita Shuhei, and presented at the last Taiwan International Documentary Festival, where it received the Audience Award.

Here the synopsis:

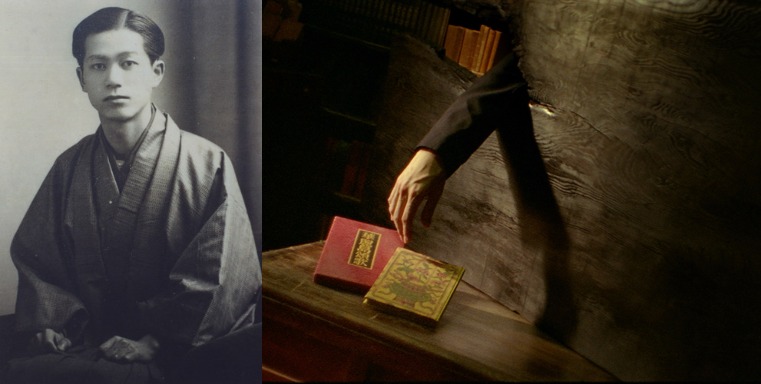

Tateshi Tetsuomi was born in Taiwan in 1905. He returned to his birthplace to find painting subjects and then he had been attracted by the landscape and local cultures of Taiwan. During his stay in Taiwan, he made oil paints, illustrations and wood engravings for the magazine Minzoku Taiwan (Taiwanese Folklore). He was regarded as a promising painter, but his achievements were to be forgotten when he was repatriated to Japan at the end of WWII and lost most of his paintings. He earned a living as an illustrator for children’s books, but finally achieved unique expressions in his last years. This film reveals his ambition and struggle, and reflects the dramatic political, cultural and social change in Taiwan.”

The word Wansei refers to the Japanese individuals born in Taiwan during the colonial occupation of the island, people who were forced to leave Taiwan, and de facto deported, in the years following the end of the Pacific War (1945). The movie, exploring the life of one of these people and a very special one, is indeed a biopic, but at the same time and on a more subtle level, it’s a depiction of what it means to belong and to live in two different cultures in times of shifting historical changes.

Tateishi was born and lived part of his life in Taiwan, a place and a culture that played a great part in his development as an artist and human being, when he returned there from Japan during the 1930s, the colors and landscape absorbed in his daily experiences would remain forever with him and would be very recognisable in his future paintings. As he writes in his memoir “I have always peferred strong colors and bold lines. Taiwan’s landscapes suited my personality perfectly”.

Things started to dramatically change in the sociopolitical environment at the beginning of the 40s, when the “divide began to emerge between Japanese and Taiwanese in areas such as painting, literature, and theater. The government was promoting Japanesation, Taiwanese culture was considered vulgar and barbaric”. In such a period, when the imperialistic and fascistic oppression promoted by Japan was at its peak and the propaganda machine was in full swing, Teteishi extensively wrote for Folklore Taiwan, a magazine (in Japanese) exploring and reviving the traditional arts and custom of the island. This (re)discovery of Taiwanese cultural heritage was so important that is still praised nowadays among Taiwanese scholars.

At the age of 39 in 1944 Tateishi was drafted and sent to the war front, and after the conflict ended his family stayed in Taiwan, part of those people called “overseas Japanese” in a land now under Chinese administration. In 1949 they were forced to leave the country and go back to Japan, where he continued to paint and eventually became a well-known illustrator for encyclopedias and scientific publications, many of his illustrations can be found in Japanese children’s books and covers of the 1960s and 70s. As for his painting, after the war his style changed considerably, becoming more surrealistic and abstract “military and post-war experiences in Taiwan cast a shadow over my heart, I searched for new styles of painting, yet I could not make up my mind on a particular style.”

From a purely cinematic point of view, the documentary is mainly composed by still photos, paintings, archival images and interviews with Tateishi’s relatives, his wife and his two sons, and Taiwanese arts scholars. The narration is heterogeneous, the main voice, the one from his granddaughter, is intertwined with short pieces read from his memoir and the voices of his wife and children. There are also few scenes of modern Taiwan and Japan, a school where he used to teach or places where he used to go, and everything is held together by a minimal and unobtrusive music, a sound design that gives the movie its almost contemplative mood.

When the story moves to Japan after the war, the documentary loses, for me, its appeal, it’s still a well crafted work, but the risk of becoming an hagiography is very strong. Fortunately balancing up this tendency are the artist’s beautiful and diverse paintings filling up the screen with their colors, shapes and mystery. Another problem I have with the movie is that the period of colonization, to my eyes at least, is depicted with some indulgence, of course the aim of the work wasn’t to deeply explore the violence of the occupation, but still, watching the documentary it seems like the period was after all a positive phase in Taiwan history, especially when opposed to the post-war Chinese administration. I am maybe reading too much into it, and again I’m not an expert on the subject, so I could be wrong and it may well be that amid all the violence and oppression, important cultural and artistic achievement were obtained, but at what price?

If raising doubts about a subject is one of the best achievements a movie can obtain, willingly or not, Wansei Painter – Tatsuomi Tateishi for what I’ve written above is certainly a compelling work and a must-watch for anyone interested in how the life of an individual interweaves and is shaped by the events of a very intricate historical period.

The next installment in my personal series about Japan/Taiwan will be, time permitting, 3 Islands by Lin Hsin-i, you can now read my review here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.