Second report from the Kobe Discovery Film Festival 2022 (you can read this first one here).

On October 15th, the festival held a couple of screenings of home movies from the Kobe area, on the occasion of Home Movie day 2022. It was a very pleasant and eye-opening experience for me, the audience had the chance to see a couple of short films (from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, if I’m not wrong), projected on screen with the person who filmed it, or a family member, in attendance. It was like opening a treasure chest, a personal one, in front of a bunch of strangers, a way to share personal memories, often forgotten, with other people. The home movie day, held since 2002 all over the world, it’s a fascinating event situated at the intersection between personal history, History with a capital “H”, and film studies. It is an exploration of the possibility of building an alternative video history from the bottom up, almost a micro history as it were, excavating personal memories to document social changes, and also an occasion to celebrate a dying format (8mm, super 8, etc.). Besides the specific places and experiences captured on the films projected—a trip to the zoo, scenes of a countryside house, a family vacation, a day at the Osaka Expo 1970—it was interesting to learn how home movies from the 60s generally retain even today a better visual quality and colours (especially the reds), compared to those shot in the following decades. As the film and film equipment got more affordable, the quality of the celluloid also dropped, causing the films to deteriorate easily with the passing of time. Insightful was also to learn, from a live commentary done by a scholar of the subject, that, because of the cost of the film, home movies made in the 50s or 60s were usually edited faster, with shorter cuts that is, while later on the cuts tended to be longer.

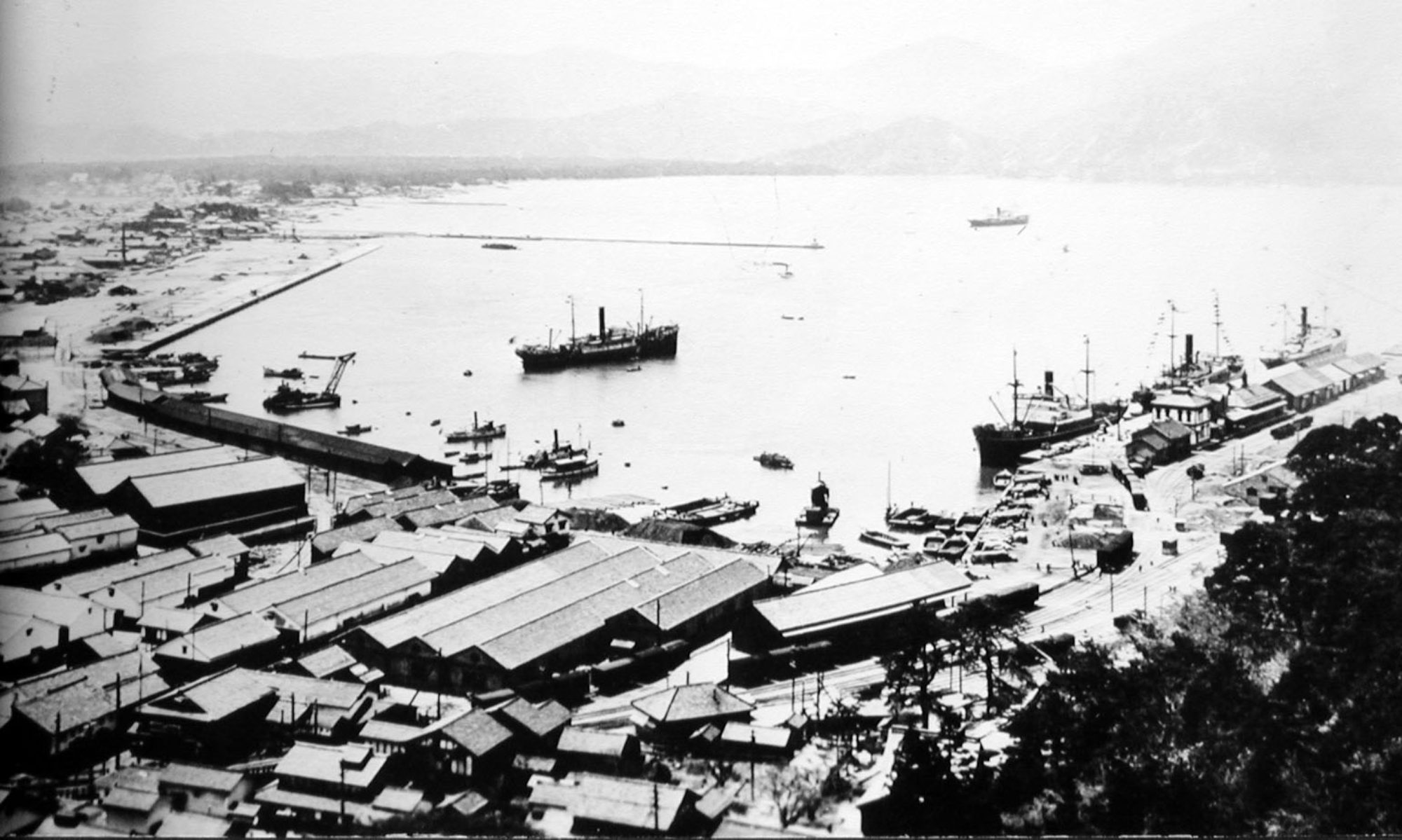

In September 1939, after the Nazi invasion of Poland, Maria Kamm and her brother Marcel Weyland were forced to leave their hometown and to start an endless journey around the globe to survive. After fifteen months in a refugee camp in Lithuania, they arrived in Tsuruga, a port city in Fukui prefecture, and from there they moved to Kobe, later to Shanghai, where the family was separated, and finally they reached, at different times, their final destination, Melbourne in Australia.

海でなくてどこに Where But Into The Sea (2021) is a film documenting their odyssey around the world, constructed by interweaving interviews, poetry, letters, and a historical investigation by scholar Kanno Kenji. The film is directed by Ōsawa Mirai, but the idea of the project came about when Kanno met Maria in Melbourne in 2016, and later decided to shape his research also into a visual work.

The documentary is a delicate portrait of two people, their family, their past, and how their personal experiences intersected the large historical events of the last century. It is also about a less known and studied fact, how the asylum process for Jewish people worked in wartime Japan and in the Japanese occupied territories.

The movie has a beautiful and poetic ending, made in collaboration with artist Miyamoto Keiko, it was a discovery for me to learn that this scene was inspired, as the director himself confirmed in the talk after the screening, by the films of Satō Makoto—specifically Memories of Agano (2005) and the movie in the movie screened on a tarp, but also Out of Place: Memories of Edward Said (2006). Ōsawa was Satō’s student when he was teaching at The Film School of Tokyo (Eiga bigakko), and he is also the director of 廻り神楽 Mawari Kagura (2018), a documentary that has been on my radar for some time.

You can read more on the official page of the project.