Directed, shot and edited by Oda Kaori, Aragane was one of my favorite documentaries of 2015, a work that came out from film.factory, a film school based in Sarajevo and founded by renown Hungarian director Bela Tarr.

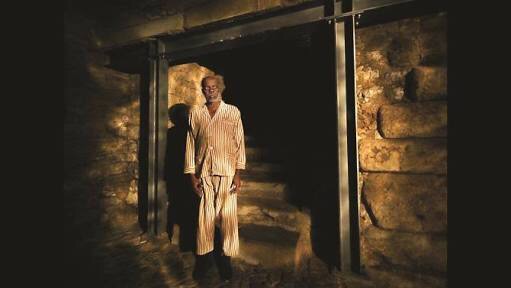

Aragane it’s an experimental documentary shot in a Bosnian coal mine, an immersive and hypnotic sensorial experience that was presented last year at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, where it got a special mention.

I wrote a review of the movie in Italian for the blog Sonatine, but I’m planning to write one in English as well and post it here, time permitting.

In October I had the pleasure of interviewing Oda for the Italian newspaper Il Manifesto, the following is the original and longer version of that interview.

Can you tell us how you got involved in cinema, that is, how you got interested in watching and making movies in the first place?

I wanted to be a professional basketball player, I played for 8 years since I was 10 years old, but unfortunately my right knee got broken. I underwent two big operations but it was not possible to keep playing seriously. Doctors said NO to me. So I was lost completely because the only thing I knew in life was basketball. I decided to go to the US to study abroad then, you know the typical thought that if you move the place, something may change in your life. There I took a film course, that was the first encounter to filmmaking, I was not cinephile at all and I am still not. (but I like some films, of course)

I made the very first film with my family in 2010 (ノイズが言うには Thus a Noise Speaks). It is a self-documentary made by my real family and myself about the coming-out as gay. The idea was to use filmmaking to communicate with my family and face the fact that they could not accept that I was gay. It was a tough experience but I learned a lot from that and started to see and use camera as a tool for communication. Communication between myself and the subject (the people/ the space).

(A still from Thus a Noise Speaks 「ノイズが言うには」)

How about film.factory? how did you happen to move to Sarajevo and be part of the group?

I got a chance to screen my first film in the student section of Nara International Film Festival in 2011, and there I met Kitagawa Shinji, the person who more than anybody else understands my filmmaking. He was the programmer/organizer of the section. The film got an audience award and we kept in touch since then. In 2012, he wrote me an email that there would be a new program in Sarajevo to support young filmmakers from all over the world. I was very much lost at that time, because it was very difficult to make my next film after a self-documentary by which I confronted the biggest conflict I had.

So I decided to apply to the program, moving to a new place and meeting new people.

Luckily, my application got accepted.

Can you tell us more about Aragane, where did the idea come from? I heard that originally it was supposed to be a fiction inspired by a Kafka story (A Visit to a Mine), is that true?

Bela (Tarr) gave us an assignment to do an adaptation work. He wanted me to do ‘Bucket Rider’ a short story from Kafka that revolves around man looking for coal. So I went to a coal mine company to do research for the project. The space and the workers were incredibly attractive, immediately I knew I wanted to shoot them as I felt and not through an adaptation work.

What was the involvement of Bela Tarr in the making of Aragane? Did he give you any suggestions, ideas or was he just supervising the project?

I brought some shots I made there and told him that I wanted to make a film. He watched them and said ‘Go and shoot’. We had one meeting when I was still shooting and I had doubts about which direction I should go with the project, should I go more for the people and their story or more with the space itself?

He told me ‘Listen to yourself, what do you want to do?’

I said ‘I am attracted to the space and the physical work of miners’

After shooting, I edited the film and showed the first rough cut to him and he gave me some comments such as ‘maybe you should eliminate this shot’ or ‘keep this one’.

More than once you’ve mentioned space and your relationship with space when making a film, I think is a very fascinating subject. When I watched Aragane I felt very strongly that it’s a work about landscapes (a dark one, the mine), the materiality of it and the machinery in it. An “alien” landscape and the beauty of it. What brought you to focus more on the space/landscape and the machinery, and is there a reason behind the use of long takes?

I think I was fascinated by the space because it was something totally new, complete darkness, magnificent volume of noises, but also sudden silence where there were no machines around.

The space drugged me into the film, my camera (gaze) was a communicator/mediator between what was there in front of camera and myself. I tried to understand and feel what was going on by shooting the space and its own time. Also, I didn’t approach the subject from the angle of the hard conditions of miners, unfairness and danger of their works (even though it is there in the film because it was just there). I hope people would not get me wrong by saying this. I/my camera shared some moments with them, I tried to be with them moment by moment. Focusing on social issue can be something good for miners, to say what is the problem and how ignorant we are about the issue, but I think the best I can do with my filmmaking is to try to be with the subject (space/people/time) and make them seen by being with them.

About the machinery, I think I shot them because their existence is big in that space and also because miners were proud of the machines, especially the huge ones digging into the side walls.

It may be a bit difficult to explain why the shots needed to be so long, but I tried to be honest toward the moments I captured with my camera.

I think the sound in Aragane is as important as the images, can you tell us more on how you were able to capture and magnify the sounds of the machines and, if you can, tell us about your relationship (as a filmmaker) to sounds/noise and soundscapes?

It is very interesting to me that lots of people mention about sounds and soundscapes. The sound was recorded with the internal microphone of a Canon 5D, because I didn’t have something like Zoom, also I was most of the time alone, so my hands and focus was with the Camera/Image. My light was on the helmet to make the curtain space visible, so it would have been impossible for me to take care of the sound recording. What was recorded was done “without care” and automatically.

I did the sound mix myself, changing the volume here and there, cleaning a bit of noises, and making rhymes/music by adding some noise on top of another noise. That was fun and I think made the film to gain a sensorial feeling.

I was just playing with sound in Aragane , but I want to learn more about sound. The film made me realize and feel that Film is an audiovisual art.

It’s interesting that you’ve used the words “sensorial feeling”, the first time I saw Aragane I thought straight away of the works of the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab (Leviathan, Manakamana, Iron Ministry, etc.), you told me already you haven’t watched their movies and that you’re not really a cinephile, but I was wondering if you got ispired for your approach by any movies or more in general by any other work of art.

After your email, Matteo, I watched ‘Manakamana’ ‘Iron MInistry’, and ‘People’s park’,

and I see what you see as similar.

It is very interesting because, before you mention about the Lab, I’ve thought that if I stop making films, I want to be an anthropologist. And I feel I am learning about human beings by making movies.

I might not be so good yet and I have not a clear idea about what I am doing with my camera, but it has been very clear for me that my theme is ‘where we come from, what we are, and where are we going?’ .

I know it sounds abstract and even pretentious, but I’m serious. I may not get the answers before I die, but I have at least the right to explore and challenge these themes with my life, I guess.

I am inspired by: Wang Bing, Pedro Costa, Raymond Depardon, Wiseman, Cezanne. My bible: Letters To A Young Poet by Rilke.

One last question: what are your future plans, are you working on something at film.factory and how about after film.factory?

I have a few projects now.

One is my essay film, to conclude the experience in Bosnia and filmmaking here. This is my priority right now. It’s in the production stage.

And then I plan to do a workshop of filmmaking/photography/camera in a discipline center in Sarajevo. (It is a institution for the underage kids who commit crimes, not strict as much as a prison). I want to share the possibility of using the camera as a tool of communication and expression with these kids. This kind of workshop is what I want to do as my life time project, I don’t know if I can finance such a project, but I want to try my best to make it a constant practice in my life.

Or I might move to Mexico to do a project after film.factory, one of my colleagues is from Mexico and I want to shoot something there related to sea/water/cave. It’s still in the research/developing stage. Or maybe I’ll go back to Japan, it all depends on if I can support myself and how these projects can be produced!

Feel free to add something you want to say or share.

So many people have been supporting my filmmaking. My family, Kitagawa Shinji, Bela Tarr, and my dear colleagues. Most of the time, I shoot and edit alone and this sometimes make me misunderstand that I am making films alone, but in fact, there is always someone who introduces the subject to me, tries to support me mentally, gives me some thoughts on the film, shares the film, writes about the film, and watches the film. All these people make films. All these spaces and times make films. I’m just one of the gears/energies that make films happen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.