A week ago, I had the pleasure of attending the opening weekend of this year’s Kobe Discovery Film Festival (October 15-16, 21-23), as always held at and organized by the Kobe Planet Film Archive. Now in its sixth edition, the event started in 2009 as Kobe Documentary Film Festival, and later changed its name and guiding philosophy (2017), when it broadened its scope to include programs about home movies, film preservation, film restoration, and the (re)discovery of less known movies from the past. I will write, time permitting, about some of the other films I saw at a different time (second dispatch is here), but today I’d like to focus on what, for me, was the highlight of the festival, a short program dedicated to two documentaries made by NDU (Nihon Documentary Union).

2022 has been a sad year for NDU’s former members, but a fruitful one in establishing its legacy in the history of Japanese cinema and beyond. Inoue Osamu, one of the key members of the group, passed away last June, and this year marks also the tenth anniversary of the passing of Nunokawa Tetsurō, one of the main figures of the collective. On the positive side of things, 2022 was the year NDU received its first official international exposure, when last spring the Japan Society in New York organized a special (online) screening of two of their best works, 沖縄エロス外伝 モトシンカカランヌー Motoshinkakarannu (1971) and アジアはひとつ Asia is One (1973). I’ve written about NDU and Nunokawa in more than one occasion (check the links below), and for a more in-depth and better written piece, check Alexander Zahlten’s The archipelagic thought of Asia is One (1973).

The two films shown in Kobe, Tokyo ’69 – One Day Blue Crayons… (1969) and Public Order Project: Martial Law at Noon (1981) – have only recently been (re)discovered or identified as works by the collective and have rarely been screened before (the latter has actually never been shown publicly). Neither is more than half an hour long, but I believe they represent two essential pieces of the fascinating mosaic that was NDU, not least because they encapsulate a certain era of social dissent, and consequently documentary making, in Japan between the late 1960s and early 1980s. After the screenings, Nakamura Yoko, a film scholar specialising in NDU, spoke briefly about the films in the context of NDU and Nunokawa’s career, which was very helpful in understanding the two films, especially Public Order Project: Martial Law at Noon.

東京’69 – 青いクレヨンのいつかは . . . Tokyo ’69 – One Day Blue Crayons . . . (1969) Shot on 16mm between 1967-68, this documentary is a propaganda film funded by the Tokyo headquarters of the Japanese Socialist Party to support Governor Minobe Ryōkichi, who was elected in 1967. While on the surface a piece of political advertising, Tokyo ’69 – one day blue crayons . . . reflects on and depicts various problems facing the capital and its citizens in the late 1960s, a time when urban sprawl was increasingly and dramatically changing. Expropriation and exploitation seem to be two of the main threads running through the film: we learn that 95% of Tokyo’s land was in the hands of 5% of the population, as redistributed after the war. The film also shows how truck drivers carry and deliver goods they don’t use or own, or how workers who come to the city from other areas live in precarious conditions. For example, we see a man from Hokkaido working almost 14 hours a day while living and sleeping in an extremely small rented room.

It is also interesting to note the focus on the lack of crèches for working women to leave their children in, a problem that still seems to be unresolved, and the criticism of the new stadium built for the 1964 Olympics, a structure that, as NDU points out, was of no use to the people of Tokyo after the games. An uncanny resemblance to what is happening now after the 2021 Games. The title of the documentary seems to refer to the final scene, in which we see a young boy drawing pictures with crayons in a sketchbook. At one point he is asked a series of questions, including “What colour is the sky?”, and his annoyed answer is always “shiran” (I don’t know). The hope is that one day the sky will be blue.

According to the festival leaflet, this film has never appeared in Nunokawa’s statements, but it is credited as an NDU production at the very end, in the bottom right-hand corner of the screen, a fact confirmed by Inoue before his death. The film was made at the same time as 鬼ッ子 闘う青年労働者の記録 Onikko-A Record of the Struggle of Youth Labourers (1969), also funded by the Socialist Party, a work that shares not only the general tone but also some famous shots. The freight train carrying petrol for American planes to Vietnam passing through Shinjuku station, and a tank parade in the middle of the city.

In its critique of Tokyo and its exploration of the dark side of the 1960s economic miracle, the documentary reminded me very much of Tsuchimoto Noriaki’s 東京部 Tokyo Metropolis (1962), a short documentary made for television that was never broadcast because it was considered too dark and pessimistic (you can watch it, in Japanese and legally, here, here)

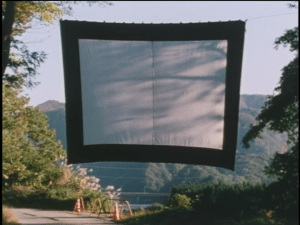

治安出動草稿 お昼の戒厳令 Public Order Project: Martial Law at Noon (1981). Shot in Super 8 by a group of NDU members in one day – though credited at the end as a Nunokawa production – the film documents the second Six Cities Joint Disaster Prevention Drill, organised in Shinjuku on 1 September 1981. When it was announced that some twelve million people were expected to take part, an astonishing and frightening number, Date Masayasu, a former Shinjuku city official turned cultural critic and writer, declared alarmingly: “We will be moved under the command of the Self-Defence Forces! “. Inspired by this comment, Nunokawa and seven other members of the collective began filming people marching and gathering in Shinjuku, protests in the streets, and military manoeuvres in Tokyo and the surrounding area on 1 September.

As is often the case with NDU’s films, especially the later ones, there is no great explanation of what is happening on screen, or the reasons for what we are seeing. As the film progresses, however, a sense, if not a meaning, slowly begins to emerge. In a country regularly hit by natural disasters such as earthquakes, typhoons and floods, emergency drills are a normal part of life, but this one felt and was very different. The connection made by Date and Nunokawa and NDU with the documentary is a subtle but deep and powerful one, at least for me. Disaster drills of this scale are deeply connected to public order and the idea of a strong and unified nation/state imposing its will from above. Self-Defence Forces landing in Shizuoka from the sea, helicopters flying constantly over the city, the sheer mass of people moving in the streets – it is worth repeating, almost 12 million people! – and the effort to coordinate six cities within the megalopolis, all this is seen and understood in the film as something dangerously close to an act of military mobilisation. The documentary is very effective in capturing and expressing this massive sense of potential fear. A past – the narration mentions, for example, the lynchings of Koreans and other minorities that continued after the great Kantō earthquake in 1923 – that could resurface at any time in the future.

Formally, the film alternates between scenes of helicopters flying over the city – the sound here is distorted and becomes almost hypnotic – and scenes of the Self-Defence Forces, sometimes in slow motion, with scenes of clashes between demonstrators and the police. It is worth noting how different the scale of the protests were from those of a decade earlier. Japanese people continued to protest and demonstrate even after the end of the so-called political season, Narita docet, but the number of people involved and the motivations changed dramatically, for reasons that cannot be explored in this piece. What stood out for me aesthetically, compared to other NDU works, was the extensive use of electronic music throughout the documentary, especially in the final part, when activists and police clash and march to the sound of electronic drums. As a mere curiosity and possible coincidence, it is interesting to note that on the same day, 1 September 1981, Kraftwerk, the German group that more than anyone else pioneered electronic music in popular culture, were also in Tokyo, ready to embark on their first Japanese tour.

The film has not been included in any of NDU’s special features to date and, as the flyer suggests, this special screening in Kobe was made possible thanks to the efforts of Mitsui Mineo, a former collaborator of Nunokawa’s and probably a former member of NDU, who worked with him on his documentaries in Palestine.

Explore more about NDU:

Alexander Zahlten: The archipelagic thought of Asia is One (1973).

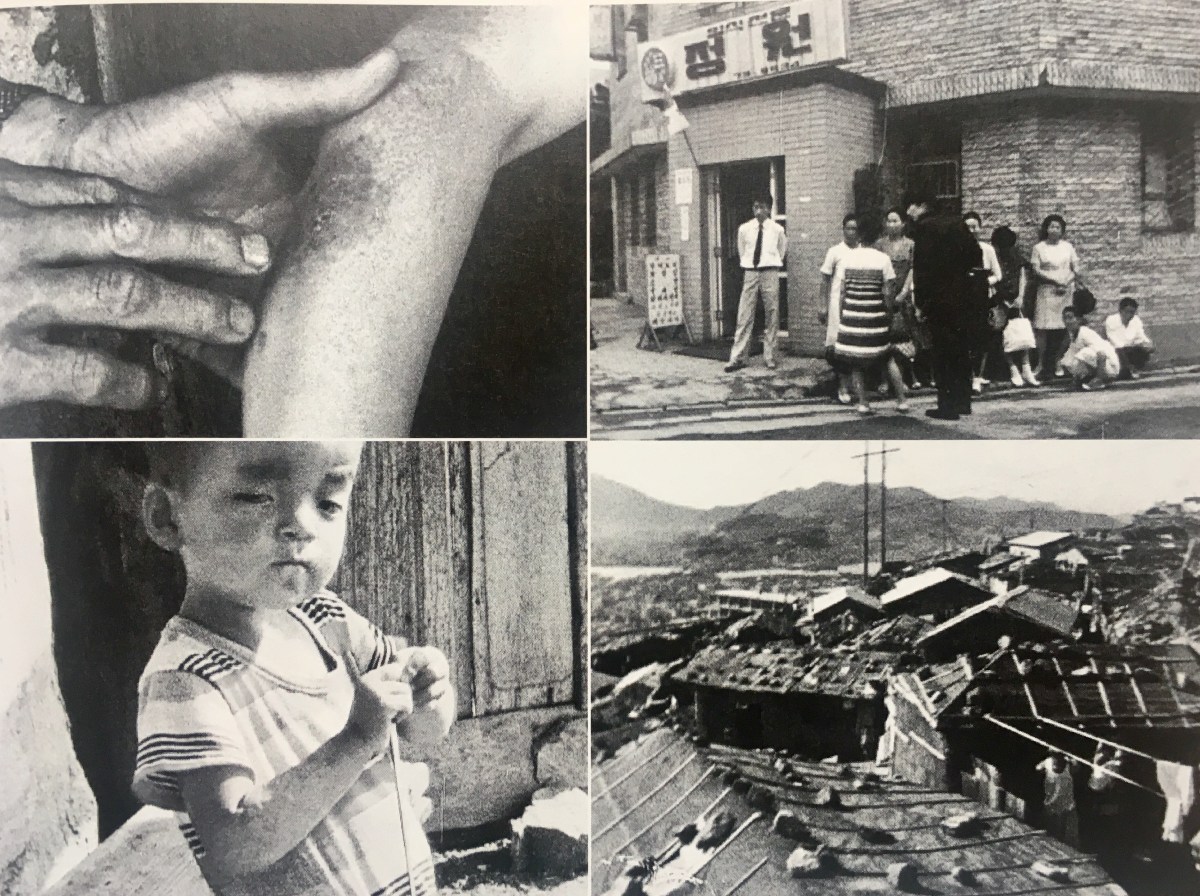

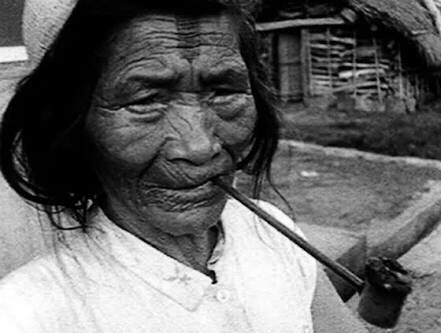

To The Japs: South Korean A-Bomb Survivors Speak out (1971)

special (online) screening of Motoshinkakarannu (1971) and Asia is One (1973) at Japan Society New York

You must be logged in to post a comment.