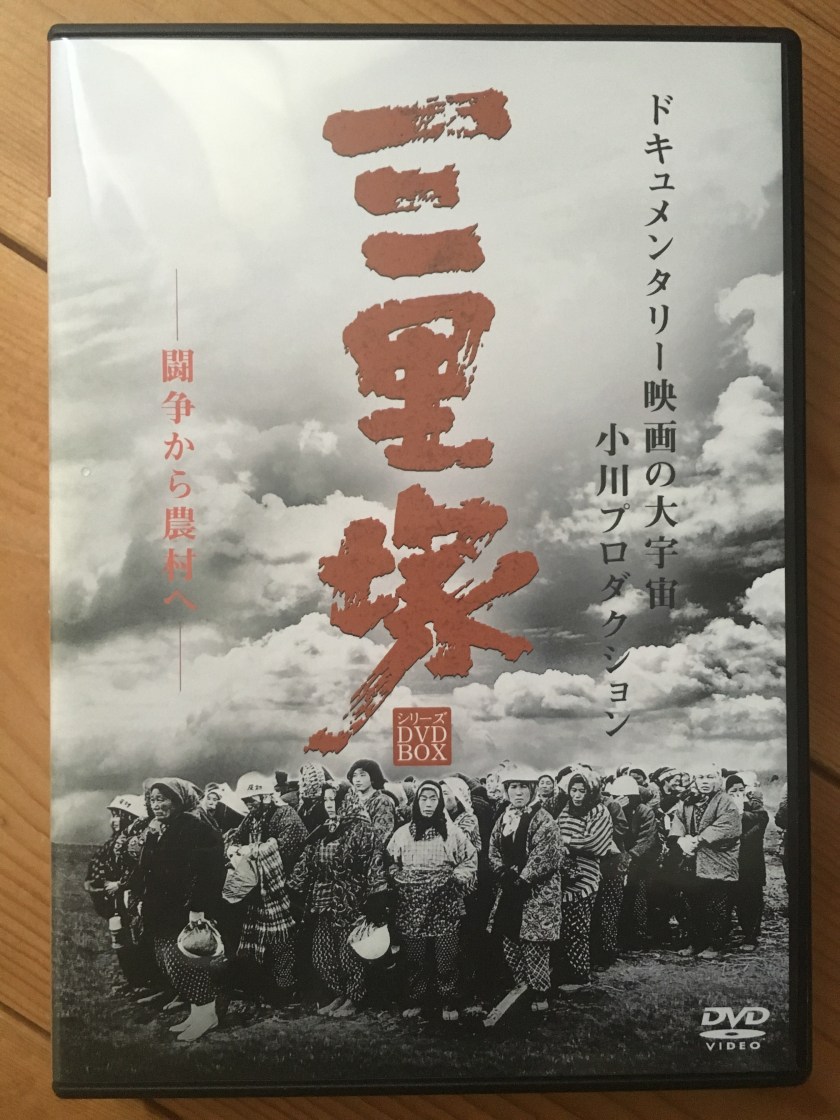

Known outside Japan as the Narita series, the works made by Ogawa Shinsuke and his collective from 1968 to 1973 (with a return to the area in 1977) filming the battle and resistance of farmers, students, activists against the building of Narita airport, are usually called in Japan the Sanrizuka series, from the name of the area where the main struggle and land expropriation took place (an ongiing battle that is not over, by the way). As written briefly in a previous post, the Japanese label DIG is putting out on DVD all the documentaries of Ogawa Production, the first 3 films were released in June, and today (July 2nd) DIG is also releasing a DVD box set of the Sanrizuka/Narita series. Here’s the list of the works included in the box set:

- Summer in Narita『日本解放戦線 三里塚の夏』(1968)

- Winter in Narita 『日本解放戦線 三里塚』(1970)

- Three Day War in Narita『三里塚 第三次強制測量阻止斗争』(1970)

- Narita: Peasants of the Second Fortress『三里塚 第二砦の人々』(1971)

- Narita: The Building of Iwayama Tower 『三里塚 岩山に鉄塔が出来た』(1972)

- Narita: Heta Village 『三里塚 辺田部落』(1973)

- Narita: The Sky of May 『三里塚 五月の空 里のかよい路』(1977)

- as an extra work, available only in the box set: Fimmaking and the Way to the Village (1973, Fukuda Katsuhiko)『映画作りとむらへの道』(1973)

The box set comes with a booklet where each movie is introduced and a final note by renown documentarist Hara Kazuo. I haven’t had the chance to watch them yet, so I can’t say anything about the transfer*.

All the DVDs don’t have English subtitles, but that fact that finally these important documentaries are available on home-video basically for the first time, the only Summer in Narita was released with a book a couple of years ago, is something to rejoice. My hope is that some label outside Japan (maybe Zakka Films or even Icarus Films, why not?) will one day in the near future put together an international edition.

* July 4th addendum: I’ve watched some minutes of Heta Village, The Building of Iwayama Tower and Narita: Peasants of the Second Fortress just to get an idea of the transfer’s quality. As I expected the DVDs mirror the quality of the original prints – I’ve seen them all on the big screen, but many times on quite battered DVD samples, so my memory might trick me here. Be that as it may, the movies are not in a good state, lots of scratches, flecks and dirt, in a perfect world they would have had a restoration first and they would have been transferred on DVD only later. But we don’t live in a perfect world and the huge debt left by the group is still hindering any “normal” process of preserving and presenting the works in a pristine state. That being said, this release is an important step anyway, because it will help to introduce Owaga Pro and its documentaries to a wider and younger audience, and just for this reason it’s a project that should be praised.

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.