This is the fourth and final dispatch from this year’s Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions. You can read the first three here, here, and here.

Founded in 2009, this year’s edition of the Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions is dedicated to exploring the possibilities and problems posed by the changing nature of moving images in our time. Titled Docs: Images and Records, the event, currently taking place at the Tokyo Photography Art Museum, features a variety of works (films, installations, photography, performances and talks) that reflect on the meaning of representation through the visual medium and, in particular, question the meaning of the word ‘documentary’, a term that has become increasingly ossified (both on the big and small screen) and synonymous with the word ‘factual’. Or, as stated on the web page of the festival:

A document is a record of fact-based information, traditionally in the form of words but more recently also as images such as photographs and moving images. The word “documentary,” meanwhile, has come to be used not only as an adjective meaning “factual” or “consisting of documents,” but also as a noun referring to a film expressing facts.

The Lumière brothers’ Exiting the Factory (1895), which is a record of people leaving a factory, is widely recognized as the starting point of the history of motion pictures. People at the time were astonished to see scenes from their everyday lives being recorded and replayed before their eyes as if the events were actually happening right there. Today, 130 years after the invention of moving images, it is entirely unexceptional for people to record and share their daily lives through photographs and videos. Meanwhile, the definition of a photograph has been expanded to include digital images and that of moving images now encompasses digital video; in digital form, these media can be manipulated more freely than before, resulting in a more complex and ambiguous relationship between facts and the images that represent them. Held on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, the Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions 2025 will focus on the transformation of these media. By examining a wide range of works through the lens of images and words, the festival will pursue a reconsideration of documents and documentary.

One of the four works commissioned by the festival this year is Spring, On the Shores of Aga (春、阿賀の岸辺にて, 2025) by Komori Haruka, a filmmaker I was familiar with through two of her previous works, Under the Wave, On the Ground (波のした、土のうえ, 2014) and Double Layered Town / Making a Song to Replace Our Positions 二重のまち/交代地のうたを編む (2019), both co-written with Seo Natsumi. While I couldn’t really connect with the latter, the former is a fascinating look at a specific and distinctive time and place in the aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami of 11 March 2011, a glimpse into people’s lives during the period of slow reconstruction when mainstream media attention is fading. What is captured on screen is the slow rebuilding of an area flattened by the ocean, but also the rebuilding of the lives of the survivors and their coping with the sense of guilt towards the dead, expressed here through a landscape cinema approach and the voices and memories of the people.

Another tragedy, and the people affected by it, is the subject of Spring, On the Shores of Aga, a tragedy of a very different kind that has almost silently struck the area along the Agano River in Niigata Prefecture over the decades. Niigata Minamata Disease occurred around 1964, during a period of rapid economic growth in the archipelago, when the Showa Electrical Company’s chemical plant in Kanose released large quantities of methylmercury into the Agano River, poisoning the food chain and contaminating the fish eaten by the people living in the villages in the region.

The lives of those affected by the disease were famously captured and depicted in Satō Makoto’s debut, Living on the River Agano (阿賀に生きる, 1992) and in part in the subsequent Memories of Agano (阿賀の記憶, 2005). I have written extensively about Satō and his documentaries, so this new film by Komori is particularly fascinating to me, not only because it focuses on Hatano Hideto, the head of the Niigata Minamata Disease Support Group in Yasuda, and his struggles and commitment to helping the victims for almost five decades, but also because it is partly a reflection on how Living on the River Agano has now become part of the fabric and memories of the area.

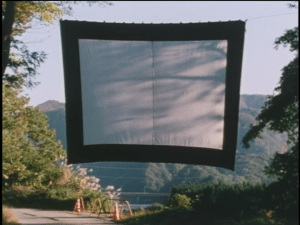

In fact, Hatano was one of the driving forces behind Satō’s debut, and over the years has been very vocal about keeping the focus on the victims of the disease and their struggles alive, even after they have passed away. Hatano still screens Living on the River Agano every year on 4 May, when he holds a memorial service called “On the Shores of Aga” to commemorate the victims of the disease and those who have worked to alleviate their plight over the years. This event is part of the activities that, as we learn from the film, he has been leading for decades, a kind of cultural movement called Meido no miyage (a final wish, something someone wants to do before dying).

Komori became interested in the Agano River and Hatano’s activities after seeing Living on the River Agano more than a decade ago, and in 2022 she decided to move to the area to film the man. While the central subject of the documentary is undoubtedly Hatano and his efforts and struggles to commemorate and memorialise the events that have shaped the Agano basin over the past sixty years, I felt that the core of the film was the sense of community forged between the very few victims still alive, their relatives and descendants, the people who have fought for their recognition, and those victims – the majority, including those depicted in Satō’s films – who are no longer of this world. This is what struck me most: how the relationship between people directly or indirectly affected by the disease does not end when someone dies, but continues to be part of an ecosystem of mourning and remembrance, made possible also by the role played by Satō’s documentaries.

The film was screened in the museum’s theatre on the day I visited, but it is currently being shown as an installation until 23 March.

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.