Kobayashi Shigeru is an important figure in Japanese documentary cinema, he was mentored by Yanagisawa Hisao—with whom he worked as an assistant director in his last two films, そっちゃないこっちゃ コミュニティ・ケアーへの道(1982) and 風とゆききし(1989)—but is probably best known for his long-standing collaboration with Satō Makoto. Kobayashi was behind the camera and an integral part of the creative process on both Living on the River Agano (Aga ni ikiru, 1992) and Memories of Agano (Aga no kioku, 2004), and in more recent years he has also been a key force in preserving and reviving the legacy of the latter film, as well as Satō’s work more broadly. Their collaboration extended also in the opposite direction with Satō editing Kobayashi’s And Life Goes On (Watashi no kisetsu, 2004). Unfortunately, of the films directed by Kobayashi I have so far seen only Dryads in a Snow Valley (Kaze no hamon, 2015), a beautiful documentary set in a mountain area between Niigata and Nagano Prefecture, which also functions as a kind of homage to Satō’s cinema.

Kobayashi was born in Niigata Prefecture and, from a young age, became involved in groups supporting the victims of Minamata disease. One of the close friends he made during this period began, some thirty years later, to experience violent flashbacks related to the sexual abuse she had suffered as a child. Around the same time, Kobayashi met a female photographer—also a survivor—who was using her photographs to support others who had endured similar experiences. These encounters prompted Kobayashi to confront his own past, suffering and growing up in an abusive family. It was at this point that he decided to make a documentary film, with the aim of helping audiences understand the reality of sexual abuse from the survivors’ point of view.

In Their Traces (Tamashii no kiseki) was presented last year in Yamagata and later on at the Tokyo International Film Festival. I missed the film during my stay in Yamagata, so I was very eager to catch up with it, and I’m glad I finally did.

The film opens with a phone call in which Kobayashi’s elderly friend tells him, matter-of-factly, that she tried to hang herself the previous night, unable to bear the recurring memories of the repeated abuse she suffered as an elementary school student.

The rawness of the subject matter, combined with the gentleness and respect with which the film is constructed, is one of the elements that makes In Their Traces such a remarkable and powerful viewing experience. A crucial decision in achieving this balance was Kobayashi’s choice to include himself as one of the film’s subjects. By foregrounding the violence he experienced—without lingering on it or allowing it to dominate the narrative—Kobayashi establishes a bond of trust with the viewer, while also underscoring the trust he built with the women who appear in the film.

It is this transparency and proximity to the other subjects that allows Kobayashi to build, on screen, resonances and parallels between the three women and their traumatic experiences. This transparency—and the trust it engenders—becomes even more powerful when the documentary, through the words of his friend (“you shouldn’t make the documentary” I’m paraphrasing), turns back on itself, questioning the very premise of the project.

The formal strategy of positioning the camera (operated by Oda Kaori), Kobayashi as director, and Kobayashi as participant as three active agents within the film’s reality enables to create a dialogic structure through which the women’s testimonies emerge in a touching and heart-wrenching manner, without ever feeling exploitative or overly dramatic. On the contrary, it is precisely the matter-of-fact quality of some of the exchanges we hear—regarding suicidal thoughts and experiences of sexual violence—that most deeply affects the viewer, making the film a profoundly empathetic experience.

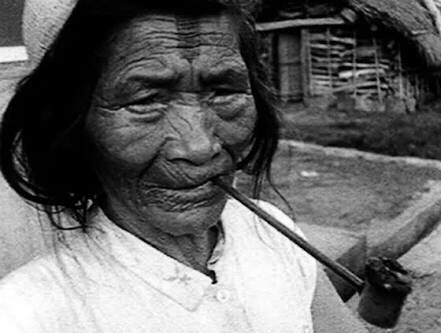

This effect is further achieved by interspersing the highly affecting scenes of conversation with striking black-and-white photographs taken by one of the women, as well as with shots of the countryside and the sea. The ocean, with its vast expanse stretching toward the horizon, has a special meaning, especially for one of the women, who describes it as offering a sense of openness and thus hope.

A fascinating point raised by the film is that in many cases the abusive fathers or male figures were themselves survivors of war or people whose lives were severely affected by war. Kobayashi has commented when talking about the documentary that his own family was reimpatriated from the former Manchuria, bearing the weight of war with them.

In conclusion, while the film loses some of its power, in my view, in the final thirty minutes—essentially from the point at which a workshop discussion about the making of the film is introduced—I found the first hour or so to be among the finest documentary filmmaking I have encountered in recent years.

You must be logged in to post a comment.