ZakkaFilms, a label specialised in Japanese movies, has announced three new releases to be included in its Filmmakers’ Market, Flowers and Troops (花の兵隊, 2009), Fukushima: Memories of the Lost Landscape (相馬看花, 2012) and The Horses of Fukushima (祭の馬, 2013) all of them by Matsubayashi Yoju. According to ZakkaFilms homepage Filmmakers’ Market is “a new marketplace for documentaries that tears down the walls separating Japanese filmmakers and foreign viewers and allows filmmakers to bring their English-subtitled works in for direct sale (..) All of the DVDs are packaged by the directors and producers themselves, so some may have only Japanese on the package or in the booklet (we note as such below), but and all of them have English subtitles.”

I had the chance to see two of the three documentaries, those about Fukushima, here in Japan on the big screen. While I liked Fukushima: Memories of the Lost Landscape – it’s in fact one of my favourite movies about Japan’s 3.11 triple disaster together with Fujiwara Toshi’s No Man’s Zone (無人地帯, 2012) – I couldn’t really connect with The Horses of Fukushima.

Here the synopsis of Fukushima: Memories of the Lost Landscape taken from ZakkaFilms homepage

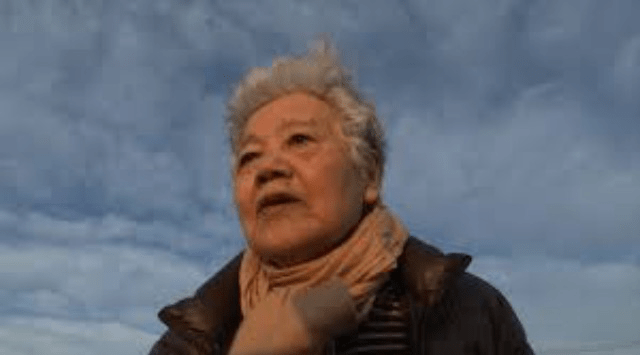

The Enei district of Minami Soma town lies within the 20 km exclusion zone around the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. In early April 2011, immediately after the devastating tsunami and nuclear meltdown forced people to evacuate the area, filmmaker Yoju Matsubayashi rushed here with relief goods. From a chance meeting with city councilor Kyoko Tanaka, he began making this film. Living together with the evacuees in school classrooms designated as temporary refuge centers, he captured an extraordinary period in the lives of the local people. Interspersed with humorous episodes and deep emotions, the film delves into memories of a local culture that has been taken away by the tragedy.

More the focusing on the place and the ruins, avoiding whenever possible a kind of disaster porn that was very present on TV and in many movies soon after the earthquake, Matsubayashi turns his camera towards the people, their memories and their stories. The more the documentary approaches its center and core, the more the shaky images and those shot from moving cars disappear, the pace of the movie itself becoming slow and more contemplative. The landscape, the lost landscape, is recreated in the film by the words and recollections of the people to whom Matsubayashi talked, or better by the conversations between them. It’s also a time-landscape, the memories of the elderly have the power to convey and embrace larger historical cycles, the conditions before the war, the poverty of the post-bellic period and the resulting process of industrialisation that forever changed the face and the balance of forces in the area, the devil pact with the nuclear industry being the most prominent one.

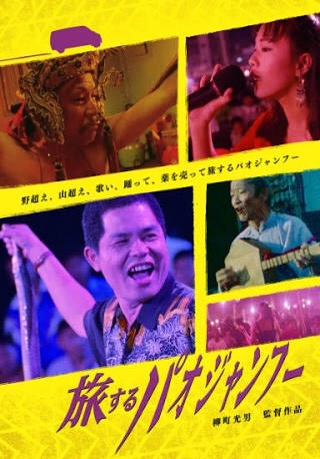

Flowers and Troops seems to be an interesting piece of work as well, a movie that explores the lives of Japanese soldiers who refused to come back to Japan from Thailand and Burma after the Pacific War, a theme that Imamura Shōhei, Matsubayashi studied with him, delved into during the 70s with several made-for-TV documentaries (they’re included in this box-set).

You can order and purchase the three DVDs by Matsubayashi directly on ZakkaFilms homepage.

You must be logged in to post a comment.