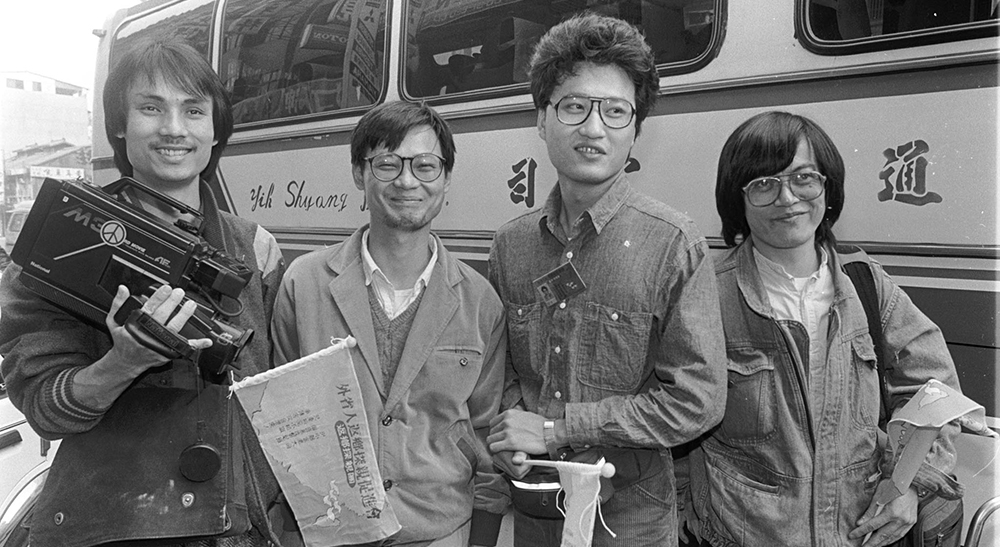

In 1979, after the Formosa Incident, Taiwanese politician Hsu Hsin-liang was forced to leave the country for his opposition to the ruling party, the Kuomintang (KMT), he would spend the following ten years in exile in the US. In 1986, after the first opposition party in Taiwan, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), was created, and while the campaign for the upcoming election was getting to the heart, Hsu tried to return to Taiwan, flying back to his country via Japan. On November 30th 1986, thousands of supporters gathered at Taoyuan Airport to welcome back the politician. Not only was Hsu not allowed to repatriate, but the central government sent a large number of police and military personnel to the airport, attacking his supporters with water cannons and tear gas. The three national and pro-government television stations used the images of the clashes to craft a narrative in which the supporters were depicted as a violent mob attacking the police. A completely different narrative emerged from a series of videos that were shot on the ground, in the midst of the clashes, by a group of DPP supporters and activists. Images that clearly showed how it was the police that provoked and attacked the people, and not vice versa. These videos were edited together to create The Taoyuan Airport Incident (1986), the first documentary made by the Green Team, a group active between 1986 and 1990 in Taiwan. The collective was originally formed by “Mazi” Wang Zhizhang, Li Sanchong and Fu Dao, and later added members such as Lin Xinyi, Zheng Wentang, and Lin Hongjun. In these four years, the collective made more than 300 works, all of them shot using video camcorders. In their works the group documented the various movements and protests that swept and destabilized the social and political fabric of the Island, in the years soon before and after the lifting of the Martial Law (July 15th 1987).

In 1998, the Green Team handed over their videos to the National Tainan University of the Arts, and 2006 saw the creation of the Taiwan Green Group Image Record Sustainability Association (literal translation). This was done in order to digitize and preserve the original video tapes (more than 3000 hours), and to set up an archive and a searchable website. Moreover, in more recent years, the works of the Green Team have been presented internationally, circulating at different film festivals around the globe. The starting point could be considered the retrospective organized at the Taiwan International Documentary Festival in 2016, where 21 works of the collective were screened on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of The Taoyuan Airport Incident. Screenings at festivals around the world soon followed, in 2017 at the Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival, in the Czech Republic, and two years ago in Rome during Flowers of Taiwan, an event organized to promote the cinema of the island. Furthermore, in the past years, the online platform DaFilms has made them available on streaming a couple of times in collaboration with Taiwan Docs.

Green Team’s videos mark a pivotal moment in the history of documentary and in the evolution of alternative media in Taiwan. During the forty years of Martial Law, documentaries were still produced in the country and enjoyed some success—the Fragrant Formosa TV series, for instance—however, practically none of them, even those produced independently, depicted and commented overtly on the social, let alone the political, situation in the country.

By documenting protests and fights related to environmental issues, indigenous self determination, and women rights, Green Team’s output opened a path that many Taiwanese documentaries would follow in the next decades. Another important novelty brought in the field by the group was the use of portable and low-cost video cameras, a technology that had become affordable and mass-produced in the mid 1980s.

The intersection of this technological shift and a mutated socio-political situation, made possible a novel documentary practice and an alternative media approach that was unthinkable only a few years before. At the same time, Green Team’s activity represented also an evolution of what had been happening since the beginning of the decade, when the media control exerted by the state started to show its cracks as a consequence of the Formosa Incident in 1979. In the aftermath of the event, political magazines critical of the government began to flourish, and in the second half of the 1980s, thanks to the aforementioned technological shift, this radical dissent took the shape of independent videos. To be in the trenches criticizing the government you needed now to bring your videocamera.

One of the VHS camcorders used by the Green Team (source)

On a purely aesthetic level, this approach resulted in works of low image quality and an almost amateurish look. After all, Green Team’s videos were never meant to be shown on huge screens and in cinemas, and by the members own admission, they never tried to make cinematic works in the first place. The group was more interested in using their videos ‘to break the barrier of media control and fulfil the concept of social practice” (Chuan 2014). This “video revolution” was made possible and successful also because of the adoption of underground distribution and exhibition practices, a clear break with what was done in the past and what was going on, at the time, in the mainstream media. I will return to this point at the end of this piece.

Labor battles and environmental protests

I have watched only a small fraction of the videos made by the collective, but two of them stood out for me, both for the topics covered, labor disputes and environmental issues, and for their construction as visual expressions. While I have touched on other videos as well, I have spent more ink, so to speak, on those two.

In 1987 alone, Taiwan saw as many as 1835 protests erupting in different parts of the island. Demonstrations and acts of civil resistance sprung up in all areas of social life: from environmental to labor issues, from student movements to indigenous rights, and from feminist fights to peasants protests. Farmers resistance is at the core of The 20th May Incident (1988), a work that documents the demonstrations of thousands of peasants in the city of Taipei, protesting against the government’s indifference to their rights and requests. It was the first farmers’ demonstration after the abolition of the Martial Law. The protest turned into an urban battle when the police stopped some farmers from using the bathrooms. Led by the Yunlin Farmers’ Rights Association and supported by a group of university students, the protesters fought back and some of them were arrested. At night, peasants and students marched to the police station, demanding the release of the people imprisoned. The police instead reacted by attacking them and arresting in total more than a hundred people.

Similar to the strategy employed during the events at The Taoyuan Airport two years prior, the national TV stations kept spreading lies through their channels, labelling the protesters as members of a conspiracy group. When the Green Team released the documentary with the images of what really happened, the government, fearing to be exposed, tried to seize the VHS cassettes of the video circulating around the country.

In 1985, the KMT government greenlighted the construction of a titanium dioxide plant, by American company DuPont, near Lukang, Changhua County. In the following months, the local residents organized a series of demonstrations that eventually caused the project to be cancelled. Lukang Residents’ Anti-DuPont Movement (1987) documents this historical victory through images of street protests, peaceful (and less peaceful) demonstrations, and discussions about broader environmental and civic issues. The work opens with a brief explanation of the situation, and interviews with the opinions of the people of Lukang. The work then moves on to show the march of the citizens in front of the presidential office to give the authorities a petition to stop the construction of the plant. Next, we see professors, poets and experts speaking at a special seminar organized in the city. This is the most insightful part of the video in my opinion, the points touched are very nuanced, complex, and more relevant than ever, even today more than 35 years later. Environment should be considered as a public asset and a collective right, says one of the speakers, and if the government is not able to protect it, it should be prosecuted. Environmental rights do not just belong to the people who are now alive, the current generation, the speaker continues, but to the citizens of the future as well. A professor of law adds that environmental rights are part of the right to life, basic human rights, and constitutional rights. In the same seminar another speaker touches on the division of labor on the global scale, that is, the exploitative nature of multinationals, in this case DuPont coming to Taiwan to use the resources of the land, without giving back anything but pollution and empty promises of “progress”.

These words provide a perfect philosophical background and set the table for what is coming on screen in the second part of the video, when we see the protests and clashes between the police and the citizens, as the distrust of the people towards the institutions has increased. It is particularly impactful to see how these demonstrations are somehow reminiscent of local folklore festivals (plus the rage). A big drum is rhythmically struck and accompanies the protest on the streets, it is often heard and seen at the center of the action, and even used as a battering ram, as it were, to break the security cordon made by riot police. Ending the video with images of a religious festival, held to express the gratitude for the success of the protests to the goddess Mazu, is thus a natural continuation of what we saw before, and a conclusion that emphasizes a reinforced sense of identity and belonging for the people of the area.

In the work, we see an organization of university students being involved in supporting the protests and in helping to do environmental research in the area. One of the major traits emerging from the works made by the Green Team, at least the ones I was able to watch, is the almost constant presence and involvement of students from various universities, but especially from the capital, in most of the demonstrations and acts of resistance that shook Taiwan at the time. This is the case with Labour’s Battle Song (Laid-off Shinkong Textile Workers’ Protest) as well, a work shot by the collective in 1988.

The film opens with a brief overview of the events that happened in Shilin district, Taipei, in 1988, when the closure of the Shinkong Textile factory left hundreds of workers unemployed and without a place to live. Some workers decided to self-organize in groups and to occupy factory spaces to express their anger towards both the company and the government. From the very first sequence it is clear how this protest is not only aimed against the closure of the plant, but also against the exploitative nature of the job. Women seem to be the ones who were more affected by the demanding labor conditions in the factory: they had to work for long hours to provide an income for their families, but at the cost of neglecting their personal lives. The documentary also sheds light on the inherent dangers of the job done in the plant and on the conditions inside the factory. This is exemplified by a very young lady without a hand, shown and interviewed during a demonstration, and who painfully recalls the incident that left her disabled.

One of the major driving forces behind the movement is a group of aboriginal students from Taitung and Hualien. As the female narrator beautifully put it, their traditional war dances and songs—performed joyfully on the street, together with factory workers and as a form of protest—bring not only a sense of needed solidarity to the workers, but have the power to “challenge the discreteness of the middle class”. Singing and dancing become fundamental elements of the workers’ identity, class identity, both during the demonstrations and in their recreational time in the occupied spaces. A particularly creative move involves turning the repetitive movements of the assembly line in the factory into a choreographed dance to perform on the streets.

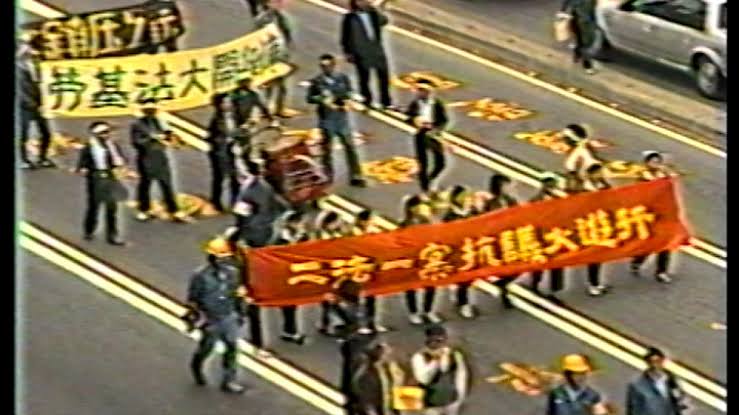

On November 12, 1988, the plant workers took part in a historical event, a demonstration joined by others labor groups from across Taiwan to protest the government’s proposed amendments to the Labor Standards Act and Labor Union Act. This event marked a pivotal moment in Taiwan’s independent labor movement, with Shinkong’s workers playing a crucial role in the fight. The class divide is a common thread permeating the whole work and that powerfully emerges when we see the workers camping on the cold streets in front of the company’s head office. It is winter and they are preparing food to share with their comrades, while life in the rest of the city goes on as usual, indifferent to their struggle.

As time passed, challenges started to surface. The company cut off water and electricity in the plant and dormitory, leading workers to question their strategy and methods of dissent. By December 23, after more than two months, many workers reluctantly started to give up the struggle as SWAT teams were deployed at the protest site. The video cut to scenes of empty factories and rooms where workers used to live, the sense of defeat brings with it also a feeling of personal loss, a period of 75 days of resistance and labor fights is ending, but with it are also fading the memories of lives lived together for years. As a counterpoint to this mood, the film concludes on a positive note, with a montage of black-and-white photos, primarily featuring female workers, set to a labor song. While this specific fight has ended, the broader message remains clear: “Oppose exploitation. Fight for equality. Keep Fighting. Tomorrow will be better!”

Underground distribution and exhibition practices

The Green Team was not the only group of video-activists operating in Taiwan at the end of the 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s, but was the one that lasted longer, and whose works had a lasting impact on future generations of Taiwanese documentarians. The importance of the group and its activities is deeply intertwined with the manner their works were produced and distributed. The group released their works through video dealers—more than sixty at the height of their activities—selling their VHS cassettes at video rental shops and at night markets, but also through branches of the DPP, and by organizing screening tours in the countryside. Free copies were also made and dispatched for political movement purposes, for The Taoyuan Airport Incident, for instance, about 2000 cassettes were produced and distributed around the country. When the videos were about the peasants’ protests, such as The 20th May Incident, the collective formed a group in charge of screening them in rural villages to spread the knowledge, spark discussions, and as a vehicle for social and political participation. The production method behind these works is also very important, at first the funding came from donations (but not from political parties), and later mainly from the sales of their videocassettes. After shooting the footage, the members of the group edited all the material and made the cassettes, when possible on the same day, and on the following day the videos were already dispatched, by car, to the selling points. This was the case for the first years of their activities at least, and since they could not stay up to speed with the official media, later on, the collective tried to set its own underground TV station, an event documented in Green TV’s Inaugural Film (1989).

The reasons for the end of Green Team’s activities are multiple. On the one hand, the technological advance that made their success possible in the first place, brought about also a cheaper reproducibility. Piracy, that is to say, copying video cassettes illegally, became a problem, and selling videos through the channels described above became, thus, unsustainable. This happened also because other groups of video activists operating at the time in Taiwan were selling their videos at a cheaper price. On the other hand, the end of the Martial Law contributed to creating a freedom of speech that allowed the traditional media, TV and newspapers, to cover social and political issues considered taboo before, making the Green Team’s videos less exceptional. In truth, the issues affecting people living at the margins of society remained still very much ignored by mainstream media, and became a topic to explore for filmmakers and groups in the next two decades.

In this new cultural landscape and mediascape, the Green Team, their videos, and their distribution and exhibition practices partly lost their raison d’être. In the second half of the 1990s, cinemas and TV became the main release platforms for documentaries, and while maintaining their independence, documentaries started to be financed by the “system”, television channels or public institutions. The average documentary filmmaker changed as well, more directors came now from film studies and were naturally more interested in making documentaries as cinematic art—the 1980s saw also the ascent of the so-called Taiwan New Wave, capped by Hou Hsiao-Hsien winning the Golden Lion for City of Sadness at the Venice Film Festival in September 1989. Not to mention the advent of the digital revolution—smaller, cheaper and more portable cameras—an event that would radically change, in the following decades, the field of documentary, allowing filmmakers to shift their focus towards more personal and individual themes.

References and further readings:

Chen Pin-Chuan “A Critical History of Taiwanese Independent Documentary” 2014.

https://greenteam.tnnua.edu.tw/index.php

Lee Daw-Ming “A Brief History of Documentary Film in Taiwan” 2013.

Lin, Sylvi Li-chun and Sang Tze-Lan Deborah, edit. “Documenting Taiwan on Film Issues and Methods in New Documentaries” Routledge 2012.

You must be logged in to post a comment.