This is an unfinished draft for an essay on Satō Makoto’s Memories of Agano 「阿賀の記憶」, a work in progress, at this stage no more than a series of random thoughts about one of my favorite movies.

last update: 26 September 2017

“…the habit of imposing a meaning to every single sign”

Trinh Minh-Ha

Satō Makoto’s documentaries seem to be (again) part of the filmic discourse in Japan, or at least on the rise in some cinematic circles, and deservedly so. Nine years have passed since his death, this year (2016) a book titled「日常と不在を見つめて ドキュメンタリー映画作家 佐藤真の哲学」(roughly rendered “Gazing at everyday and absence, the philosophy of documentarist Satō Makoto”) was published and a screening of all his documentaries, followed by discussions and talks, was held in Tokyo in March and later at the Kobe Planet Film Archive. I haven’t read the book yet, but the title summarizes and conveys perfectly the themes embodied in Satō’s last works: the dicothomy absence/presence and the presence of absence, that is to say the phantasmatic presence of cinema.

Sato’s final works, Self And Others, Memories of Agano and Out of Place: Memories of Edward Said witness and embody a shift in Satō’s approach, movies through which he was attacking and partly deconstructing the documentary form, to be fair with his works though, it’s a touch that was partly present in his films since the beginning, but in these three documentaries it becomes a very prominent characteristic. This publication seems to be timely and enlightening because is tackling Sato’s oeuvre not necessarily from a purely cinematic point of view, the book’s curator is by her own admission not a cinema expert, but it’s expanding the connections of Satō’s movies and writings towards the philosophical.

I hope the book will kindle and revive a new interest on his works, Satō is in my opinion one of the most important Japanese directors of the last 30 years, and sadly one of the most unknown in the West, I don’t really think there’s much out there in the internet or on paper about Satō, nor in English nor in other non-Japanese languages, and it’s a pity and a missed occasion because his movies, again, are more than “just” documentaries, or even better, are documentaries that have the power to question their own form and stretch in many differents areas. If you’re not familiar with his works, you can get a glimpse of Satō and his touch reading this beautiful and long interview, or you can buy them on DVD thanks to Siglo, it’s a rarity in Japan, but they come with English subtitles.

This year (2017) Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival will also hold a retrospective for the 10th anniversary of Satō’s death, commemorating and celebrating his works, his influence and his reception abroad.

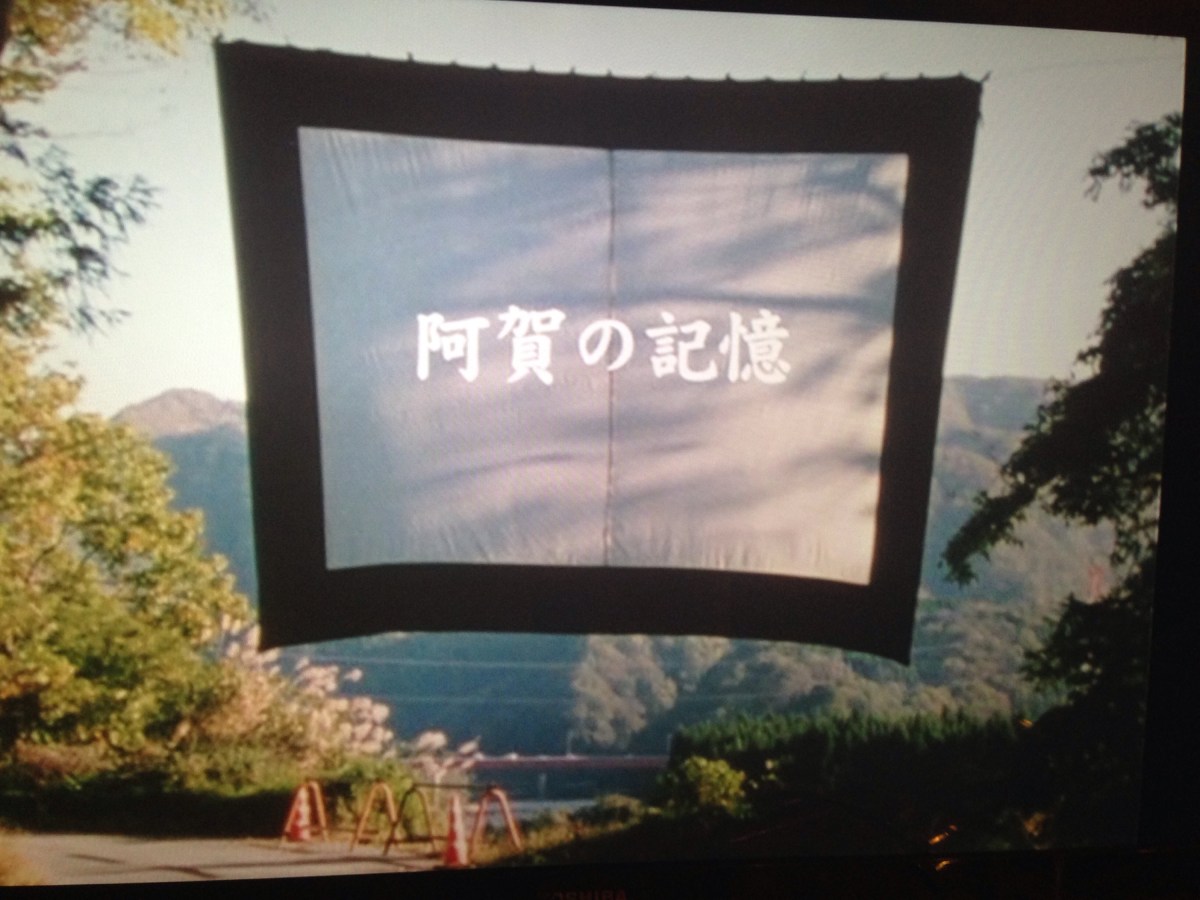

One of Satō’s documentaries that resonates with me more than others, even after many viewings, is Memories of Agano (阿賀の記憶, 2004). As the YIDFF describes it:

Ten years after the acclaimed film Living on the River Agano, the film crew returns to Niigata. Personal memories reflect upon remnants of those who passed away as the camera observes abandoned rice fields and hearths that have lost their masters.

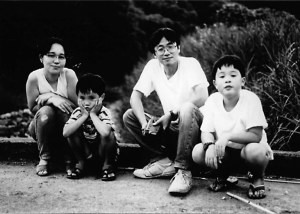

It is a relatively short but complex movie running only 55 minutes, an experiment in the form of a non-fiction film, splendidly shot on 16mm by cameraman Kobayashi Shigeru, the same cameraman who worked and lived together with Satō in Niigata for more than three years during the shooting of Living on the River Agano. The film is a poem on the passing of time and consequently on the objects that will outlive us, the persistence of things in time, including cinema itself. The original idea was in fact to make a film about the remnants of Meiji, that is “the glass photographic plates of the Niigata landscape from the late Meiji to early Taisho era (1910s) left behind by photographer Ishizuka Saburo. Using those old black and white photographs as a motif, we started out making the film with the same concept as Gocho Shigeo in Self and Others”. This quasi-obsession with objects is the thread that waves through the film’s fabric: boiling tea pots, old wooden houses, tools…

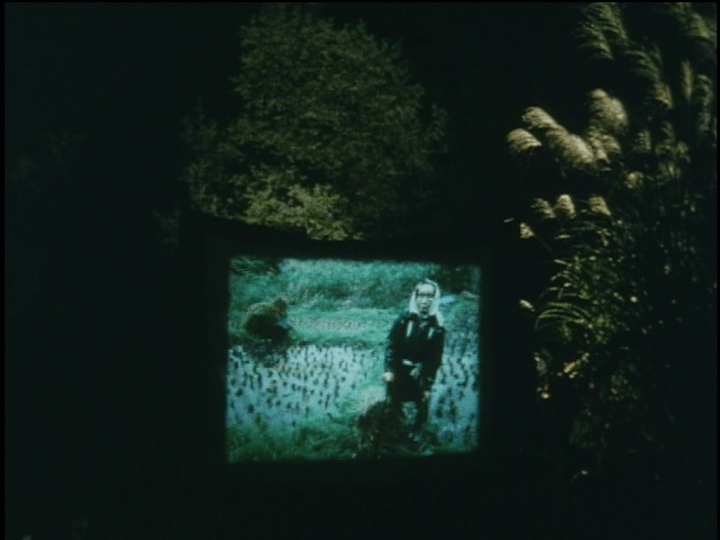

One of the most stunning scene of the movie and one that defines Memories of Agano is placed at the very beginning, when Satō and Kobayashi after returning to the area where the first movie was shot hang a big canvas tarp in the middle of a wood projecting on it the documentary they made 10 years before. The effect is profoundly disturbing and touching at the same time, images and thus memories are suddenly like tangible spectres.

On another level, Memories of Agano with its intertwining of past, present and landscapes ー the external ones with mountains, fields, rivers, and the interior landscapes of old and almost empty houses ー could also be read as an attempt to approach and partly re-elaborate the fūkeiron-cinema, the theory-of-landscape-oriented-cinema, 「footnote: “launched” almost five decades ago with A.K.A. Serial Killer (1969), The Man Who Left His Will on Film (1970), Red Army/PLFP: Declaration of World War (1971) and The First Emperor (1973)」

As for its aesthetics, one of the quality that strikes me every time I rewatch it, is the slow pace and the use of long takes that give the movie a dreamlike quality of lethargic torpor. The scene that embodies at most this aesthetic idea is an almost static shot of a teapot boiling on an old stove lasting about 10 minutes, on the background, sort of white noise, the words of an old lady spoken with a thick Niigata accent. She talks sparsly with Satō himself also about the fact she doesn’t wanna be filmed, half jokingly half seriously, a breaking of the fourth wall so to speak, a dialogue between camera and object filmed that was prominently present in Living on River Agano as well (“Are you filming me?” “Don’t shoot me!” are sentences that punctuate the course of this movie and the one made in 1992).

Memories of Agano also present itself as a documentary of opacity rather than one of transparency, the choice of not using the subtitles when people speak with their thick Niigata accent, a Japanese citizen from another area of the archipelago would probably understand 50% or 60% of what is said, a technical option that was used in Living on the River Agano – signals a major change in Satō’s approach to documentary and cinema in general. Feeding the viewer with limpid and clear messages and making a “comprehensible” movie is not what interests Satō here, but rather placing obstacles, visual riddles so to speak – the aforementioned tarp for instance, but also visually striking moments of pure experimentation – and thus presenting the opacity of the cinematic language seems to be the goals he had in mind when he conceived Memories of Agano. The images are thus escaping the organizing discourse tipical of so many Japanese documentaries, in contrast they open to new (cinematic) discoveries and keep resonating with the viewers and engage us on many different levels.

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.