I’ve decided to publish here my essay on three films by Oda Kaori that was originally meant to be published in an international film magazine (things have stalled, unfortunately). I took the decision because in the meantime Oda’s career (the piece was written almost five years ago) has evolved significantly, with more exhibitions, art installations, political and social stances, and films (Gama, and the Underground project).

It goes without saying that now I would write the piece quite differently, mainly in style but also regarding the content. Posting here this short essay does not preclude that in the future I might return to write on the subject; on the contrary, it gives me the chance and the peace of mind to turn the page and freshly reassess the filmography of one of the most fascinating artists working in Japan today.

The essay is available in PDF format here

April 2020

Reassessing the human: three experimental documentaries by Oda Kaori

“The landscape thinks itself in me and I am its consciousness.”[1]

A worker sits down and takes a break. In the deep belly of a mine and enveloped in a pitch black surrounding, he bites a red apple. His helmet lamp provides the only few blades of light in a scene of almost Vermeer-like beauty. In the preceding scenes the noise from the machinery at work in the mine is so unbearable that the words are oftentimes superfluous or just a waste of energy. The life in the mine is only silence or cacophony: there is no middle ground. It is an alien landscape, both visual and sonic, where the human is just one element among several. The beauty of the moment derives from the interplay between darkness and light, from the silence after the wall of noise that precedes it, and from the empathy towards the man conveyed by the camera.

The scene is one of most significant and impressive passages in Aragane, a feature documentary shot, edited, sound-designed and directed by Oda Kaori in 2015. Oda made her debut in 2010 with the short Thus a Noise Speaks, a personal documentary that unflinchingly explored her coming out as gay and the subsequent reactions from her family, especially her mother. The experience of Thus a Noise Speaks, one where the camera is also used, in Oda’s own words, “as a weapon for revenge against my mother,” was a fundamental experience for the young Japanese director, who was 23 years old at the time: Not only because it was a way of expressing her true self, but also because it was a chance to grasp the incredible power that filmmaking can have, and to realize how harmful a camera pointed at someone can be.

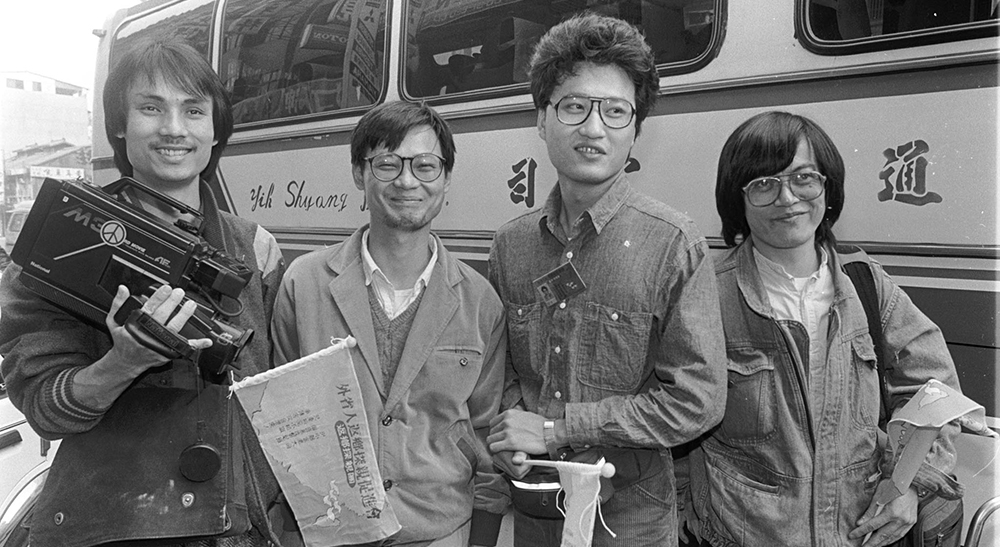

Born in Japan, but partly educated in the U.S.[2] and with three formative years spent in Bosnia, Oda’s artistic arc began from a position of hybridity from the very beginning and afterward wandered around the globe in search of places and stories to explore. The sense of displacement experienced and expressed in her debut short, and her background as a so-called “halfie,”[3] opened the gates for a cinema conceived as a nomadic wandering, and an artistic path that in crossing borders, cultures, genres, and styles, explores what it means to be a subject in flux and always open, as the best ethnographers always are, to what the world has to offer[4]. Moving from one geographical area to the next, from Japan to Bosnia, back to Japan and then to Mexico—but a Mexico filtered through Mayan mythology—Oda’s filmography expresses the idea of a nomadic cinema not interested in broad and essentialist discourses about cultures, but more focused on specific places and the collective experiences and memories linked to such places.

Towards an alien phenomenology

The first (and to this day, most artistically accomplished) example of this approach arrived for Oda in 2015, when Aragane was presented at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival. A work, as previously mentioned, that she directed, photographed, edited, and sound-designed, but also a “product” of Bela Tarr’s film.factory, the short-lived film school based in Sarajevo and established by the Hungarian director in 2013, a place where Japanese director Oda studied for three years.

Aragane, meaning ore or small pieces of stone in Japanese, was shot in a Bosnian coal mine as a project for film.factory. An immersive and hypnotic sensorial experience, the movie starts, and thus sets the tone for the rest of the work, with a pounding noise and a close-up of a machine. The scene is followed by a short depiction of life on the surface, with workers preparing and completing various tasks before commencing the deep dive into the mine. Once in, we’re in a different kind of world, one where the only lights rippling and dancing in the total darkness are those of the headlights of the workers and of Oda herself, and one where the noise is so deafening and monotonous it turns into a sort of alien music.

Aragane is not a direct inquiry into the harsh conditions of the people working in the mine (although that is something that eventually and necessarily emerges) but more an attempt to convey on screen the time and space of the coal mine as experienced by the people working in it. Creating a sensory experience of the place, an experience constructed through the interplay of machines, darkness, head lamps and the miners, Oda hints at a different field of perception and at a different type of time. For most of the duration of the film, we don’t really know what’s going on and who is doing what: what is missing is a central orientation, a focal point around which the movie can organize itself in the usual sense.

“The darkness, no sunlight, no moonlight”

“timber dust floating”

“pump, electric saws”

“grey fog”

“steam evaporating from T-shirts”

“a flickering head lamp sways”

“A small universe within a universe”.

“I see because there is light”

“In this underground world people and machine carry the same weight”[5]

Once we get accustomed to the things, events and musicality of the noise presented on screen, though, everything slowly begins to make sense. What starts to surface from the images, sounds, tracking shots and slow and hypnotic camera movements, is the time and the materiality of the mine itself. When a long and dark scene towards the end of the movie, with the carts ascending to the surface of the earth, is brutally interrupted by a static image of the outside of the mine covered in snow, it is almost like a revelation. After an hour of darkness inside the bowels of the earth experiencing a different perception of time and space, the whiteness of the snow, the colors of the clothes and those of the equipment hanging are so sharp and bright that gazing upon them almost induces vertigo.

With the sensory and cacophonic descent into the alien landscape that is the life in the mine, Aragane is also an exploration of the relation between the people working inside and the place itself. This is a crucial point in understanding Oda’s works: her films are, for the most part, and especially on first viewing, an overwhelming visual and sensory experience that seem to focus more on the non-human elements of what is filmed. However, when fully absorbed, they reveal the true potential of what her cinema can do at its best: establish a cartography of non-human landscapes and, at the same time, reflect on the role and position of the human element in this “new world.” It is not by chance that the central part of the movie, the core and one of the most significant scenes in the entire documentary, is the beautiful scene that we have described at the very beginning of this essay.

“Tell me how I can touch a butterfly without breaking her wings”[6]

The preoccupation towards people is one of the central themes of Towards a Common Tenderness. Released in 2017, the movie is many things: a visual poem structured like a diary about the experience Oda had while filming her first and second works, but at the same time a reflection on the act of filming, and, as in Thus a Noise Speaks, the power the camera has when pointed at someone.

The movie starts with a beautiful murmur of voices and sounds, with Oda herself pronouncing lines from her memories and reading from Notes on Cinematography by Robert Bresson and Rosemary Menzies’ Poems for Bosnia. It then moves to a shot of her first movie (a shot of a shot) of her mother crying when Oda comes out. The movie is, in fact, structured as a long letter sent to Oda’s mother, in which the director speaks directly to her mother about her experiences with the camera and everything that happened to her after she decided to become a filmmaker. Toward a Common Tenderness uses a mixed visual style, with abstract and poetic images intertwined with shots recorded by Oda in Bosnia and Herzegovina during her period at Bela Tarr’s school, outtakes not used in Aragane, and other images from unfinished projects.

The central part of the documentary is when Oda was a guest at a family of Romani descent for a week. When talking about this experience, she recalls how she couldn’t finish filming the project because she could not stare at the old husband and go deeper inside him, depicting the loss and grief his family went through when one of their members passed away. Rosemary Menzies’s poem shown at the end of the movie through extreme close-ups of the printed page is exemplary of the conundrum that haunts and informs the whole movie. “Tell me how can I touch a butterfly without breaking her wings.” How can we gracefully depict the beauty of things without destroying it? How can we film reality without annihilating it or destroying the things and the people in it?

“…reveals the base of inhuman nature upon which man has installed himself”[7]

If Aragane is a movie revolving formally around darkness, slow movement, and repetition, and Towards a Common Tenderness a reflection on the riddle that is the act of filming, Cenote is a movie that combines the two approaches.

It is about water, light and their connection to the cosmos, but also about people and their collective memories. Cenotes, or ts’onot in a form of Mayan, are natural sinkholes found in the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, the only source of water for people living far away from rivers or lakes, and considered sacred places in ancient Mayan civilization.

Abstract images of the underwater world inside the cenotes intercut with people reciting, almost whispering, old Mayan poems, and other voices, in Spanish, recalling memories about life near these natural pits. Swimming in the water, the camera is enfolded in a reality that is perceived and created by the play of water and light. The first ten minutes, the more experimental part of the work, are in this sense an absolute bliss, an exhilarating and liberating artistic experience that brings us back to the womb of the earth, to the origin of life, or, as one of the quoted Mayan poems states, to the place where the sun sinks, disappears and reappears every day. Blotches and blades of colors flash on screen, drops of water dance like subatomic particles on the surface of water, and fish swim as peacefully as ancient deities. While this formal experimentation is noticeable in the path blazed by Aragane, a cinema of sensation that shifts the representation of humanity towards the periphery of reality, the non-human elements presented in Cenote expand further, reaching the spiritual and the mythical.

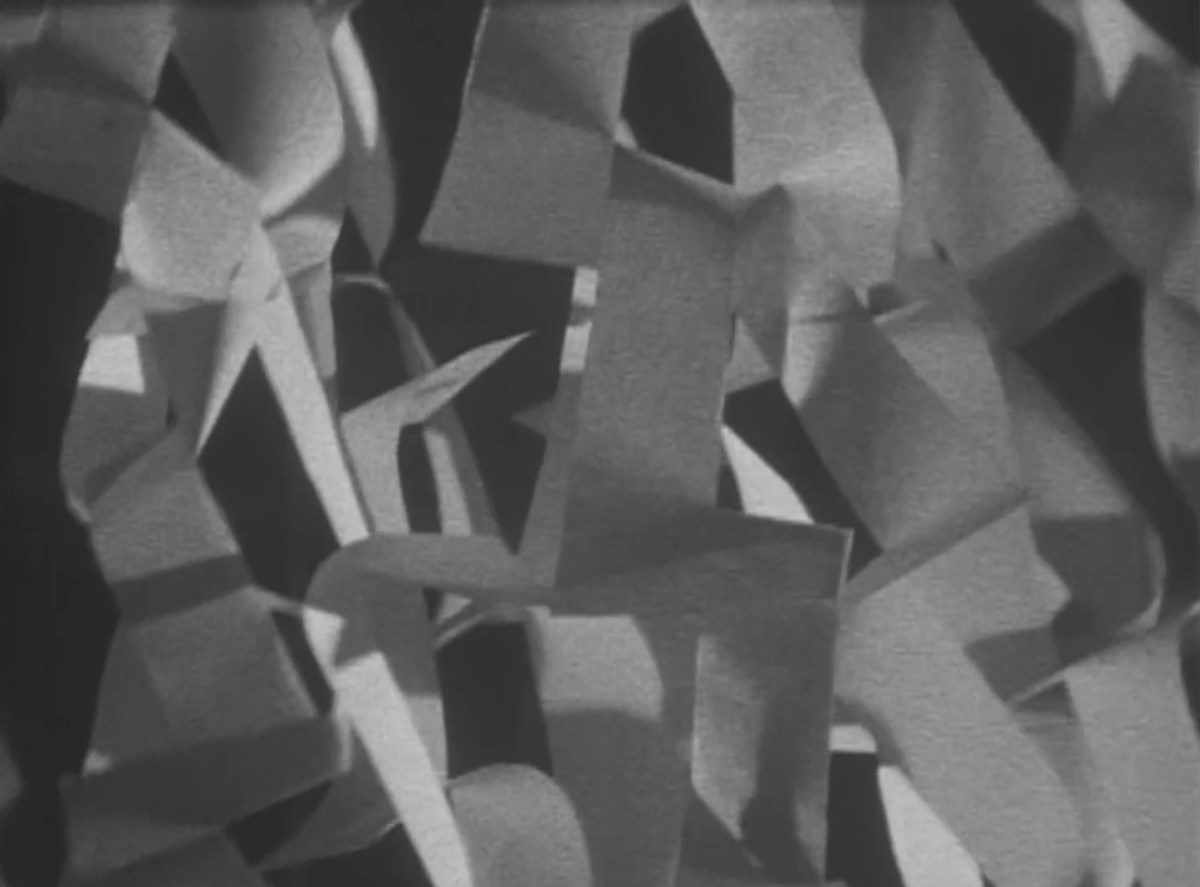

Another novelty that Cenote brings when compared to Aragane or even Towards a Common Tenderness is the presence, throughout the film, of a dialogic tension, both aesthetically and thematically, between words and noise, light and water, grainy images and digital sharpness, mythical time and geological time, and people and natural elements. Using 8mm film (Super8) and images shot underwater with an iPhone, Oda creates a difference and an aesthetic space, a poetic “ma” (間) that reflects and has a parallel in the space between the two worlds explored: the sensory experience taking place underwater, on the one hand, and the close-ups of faces and the voices of people on the other. Faces of people, but also animals, chicken, butterflies, dogs, cats, and local festivals are filmed in 8mm, while the world inside the cenotes is filmed with an iPhone. The dialog between these two types of images, the intercut between these two worlds, becomes the structural backbone around which the movie develops.

The sound and words spoken in the movie, folklore, mythical stories, memories of people who live near a cenote, and legends of children who drowned in them are all weaved together, recited and spoken in Yucatec Maya and Spanish. The stories told are important, of course, but the musicality of the words is an element that, paired with the underwater sounds and the distorted noise captured or created by the camera’s microphone, form a sonic tapestry of rare beauty. The soundscape used in Cenote, more than the one adopted in Aragane, where the human voices were relegated to very few words, hints at an idea of the cosmos in which humans are part of a larger dimension, both in time and space. The images confirm this larger scope on a geological scale: the sinkholes are a product of a celestial encounter between a shower of meteorites and the earth’s crust, but at the same time, a mythical place for ancient Mayan civilization, a portal and a threshold where, according to the Popol Vuh, this world and the afterlife touch each other. The connection between these two realms is an important part of Cenote, and, as a matter of fact, the movie also works as an exploration of collective memories and ancient mythologies, both still very present in the area and the villages around these sinkholes. The dead (via the poems), the women sacrificed in the pits, and all the legends and stories retold by the villagers, form a layer where the past, real or mythical, and the present coexist. This present-permeated-by-the-past has a phantasmic quality channeled into the movie by the images in 8mm, which always feel distant from the here and now, and by the voices in Spanish and Yucatec Maya, always out of sync and hovering above the images, as it were. The connection between the dead and the living is made more explicit in a brief and beautiful passage when the movie gazes, bathed in a frail and milky light, at funeral rituals in the area, when human bones and skulls are brushed, polished and collected with extreme care as remnants of past lives.

Conclusion

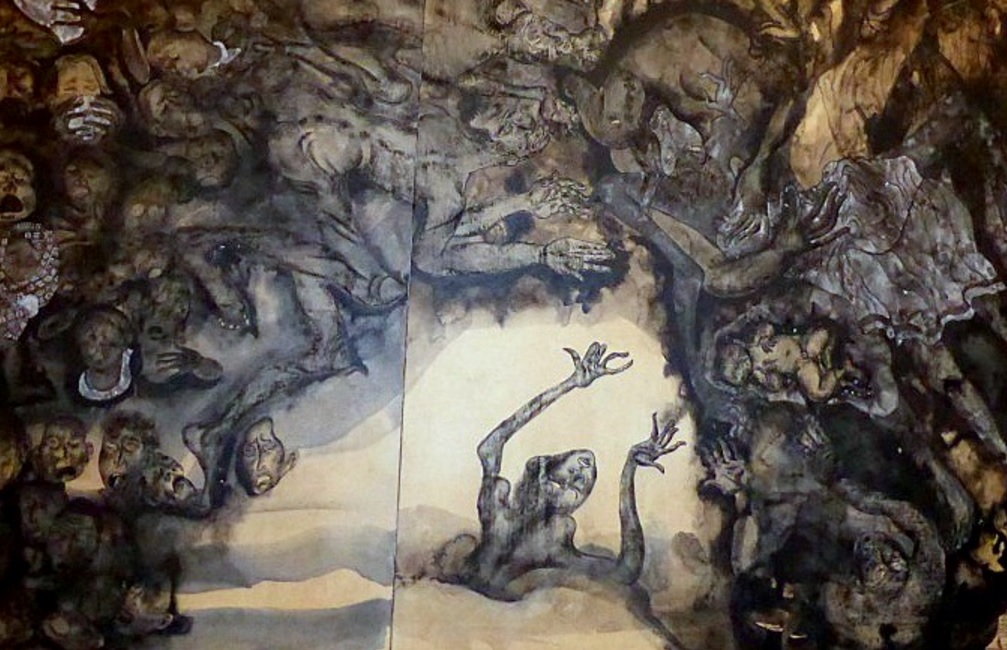

Like some of the works made at the Sensory Ethnography Lab[8], and to the cinema of Bela Tarr and Wang Bing, Oda’s filmmaking has, in the past years, built a unique trajectory in the film world: a brand of experimental documentary born at the intersection between visual anthropology and a cinema that prioritizes a pre-reflective engagement with the world. The result is an oeuvre that traces and establishes new connections between people, things, memories and the landscape they inhabit and from which they emerge. The human element is thus repositioned and reframed according to a different vision of reality, compared to one that often dominates the field of documentary, especially in contemporary Japan. This artistic approach is also traceable in her works as a painter: for instance, in a series of CD covers of Aragane’s soundtrack she painted by hand. Each cover is a thick impasto depiction of a scene from the movie, or a memory from her filming inside the mine. Another example is a series of portraits of women Oda made inspired by the story of the women who were thrown into the cenotes as ritual sacrifices. In these paintings, the faces of these women seem to resurface from the water like deities, made by the recollection of what Oda experienced while filming and swimming in these sinkholes.

Visual and sonic experimentation which engages with the world and creates a cinema that, while reassessing the human element and abandoning a human-centered perspective on reality, continues at the same time to show a deep care, affection and interest toward people. This is the biggest accomplishment of Oda’s artistic trajectory so far.

[1] Paul Cézanne, quoted in Cezanne’s Doubt, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, 1945. Later in Sense and Non-Sense, trans. by Hubert and Patricia Dreyfus (Evanston: Northwestern, 1964).

[2] She studied film at Hollins University in Virginia.

[3] “People whose national or cultural identity is mixed by virtue of migration, overseas education, or parentage” Lila Abu-Lughod, Writing Against Culture, in Fox, Richard G. Hg, Recapturing Anthropology: Working in the Present. Santa Fe, S. 137–162.

[4] More than fifty years before, a similar approach to documentary was proposed by Matsumoto Toshio: “Matsumoto’s avant-garde documentary theory focused instead on the revelation of the existential force of an object or the actual people filmed through the process of subjective film-making” Hata Ayumi, ‘Filling our empty hands’: Ogawa Productions and the politics of subjectivity in H. Fujiki, A. Phillips ed. The Japanese Cinema Book, Bloomsbury 2020.

[5] From Toward a Common Tenderness

[6] Poem by Rosemary Menzies’ quoted in Toward a Common Tenderness

[7] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ibid.

[8] At the time of Aragane’s release, Oda had not seen any works made by, or in connection with, SEL.

You must be logged in to post a comment.