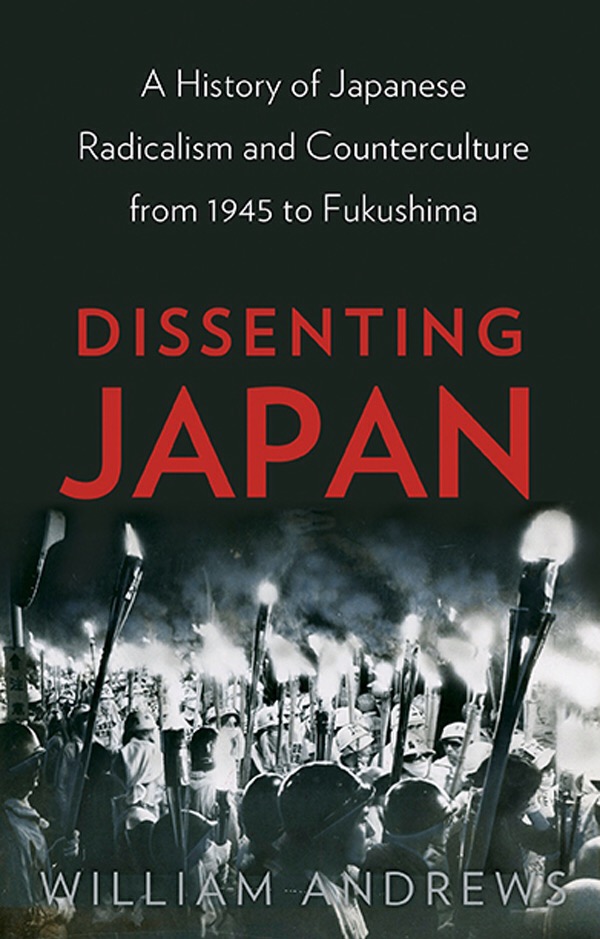

Just a quick post to draw your attention on a significant book that the London-based Hurst will publish next September. The volume is titled Dissenting Japan – A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture and is written by the Tokyo-based writer and translator William Andrews, who by the way runs an excellent blog on the same topic here.

Here’s the description from the publisher’s homepage:

Following the March 2011 Tsunami and Fukushima nuclear crisis, the media remarked with surprise on how thousands of demonstrators had flocked to the streets of Tokyo. But mass protest movements are nothing new in Japan. The post-war period experienced years of unrest and violence on both sides of the political spectrum: from demos to riots, strikes, campus occupations, factional infighting, assassinations and even international terrorism.

This is the first comprehensive history in English of political radicalism and counterculture in Japan, as well as of the artistic developments during this turbulent time. It chronicles the major events and movements from 1945 to the new flowering of protests and civil dissent in the wake of Fukushima. Introducing readers to often ignored aspects of Japanese society, it explores the fascinating ideologies and personalities on the Right and the Left, including the student movement, militant groups and communes. While some elements parallel developments in Europe and America, much of Japan’s radical recent past (and present) is unique and offers valuable lessons for understanding the context to the new waves of anti-government protests the nation is currently witnessing.

Who’s is familiar with documentary cinema (and cinema in general) knows very well that radicalism, dissenting, resistance and counterculture are a very important part of the vocabulary that defines the post war Japanese non-fiction landscape, and the fiction as well, especially during the 60s and 70s. Ogawa Production and Sanrizuka, Tsuchimoto Noriaki and Minamata, NDU and Okinawa and the borders, but also Kamei Fumio and his Sunagawa Trilogy, maybe the first Japanese works to fully embody this “philosophy” of resistance and struggle on film (excluding the Prokino before the war of course).

For all these reasons, Dissenting Japan will probably be (I haven’t read it yet) a very important read not only for historians but also for film scholars interested in Japanese cinema and in documentary in general. I’ll certainly write more about it when the book is out.