When last August I attended the Image Forum Festival in Tokyo, one of my regrets was not having the time to be at a special focus dedicated to photographer and filmmaker Yamazaki Hiroshi. As I wrote in my report, one of the good points of the festival is that it is touring, although with a downsized program, in other parts of the country. When I saw the schedule of the screenings in Nagoya in September, I seized the opportunity and spend an afternoon immersing myself in the experimental films of Yamazaki.

Born in Nagano Prefecture in 1946 Yamazaki Hiroshi became a freelancer photographer after dropping out from Nihon University where he studied at the Department of Arts. Parallel with his career in photography, for which he is known in Japan and at an international level, some of his works are displayed at MoMa, Yamazaki developed a passion for the moving image and in 1972 started to shoot short movies in 8mm and 16mm. His experimental short films are a natural continuation of his work in photography, albeit there’s an obvious difference in tone between the two. Moving freely back and forth from still photography to moving images, Yamazaki’s central preoccupation throughout his career has remained the same: the role light and time play in creating images through the mechanical apparatus. His photos are thus not about depicting human beings, situations or even landscapes, they’re more on the verge of creating and conveying something new, something that is dormant in the everyday reality and must be brought to the surface to be seen. Almost like an artist playing with the relativity theory, by distorting time Yamazaki is modifying the shape of light and thus the reality he presents in his works. Often, and rightly so, defined as conceptual photographer, his works are more akin to the paintings of Klee, Pollock or other artists who were shifting the limits between natural representation and abstract art, that to the works made by his contemporary colleagues.

Yamazaki got his first big recognition in 1983 for a series of time-exposed photographs of the sun over the sea, one of the themes that he has been pursuing and investigating throughout his entire career, and a theme very present in all the works screened at the event.

Eighteen works were screened, some in their original format (8mm, 16mm), some others digitally, and they were divided into two sections. The last film screened, The Seas of Yamazki Hiroshi, was an homage to Yamazaki as an artist, friend and peer by photographer Hagiwara Sakumi. Planned and organised by the festival as a special screening to honour and remember an important Japanese photographer and filmmaker, it was for me a special occasion to experience, in one sitting, the attempts and experiments of an artist I didn’t know in a new medium. Here the works screened:

FIX YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 5min. / 1972 / Japan

FIXED-NIGHT YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 6min. / 1972 / Japan

FIXED STAR YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 7min. / 1973 / Japan

A STORY YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 6min. / 1973 / Japan

60 YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 1 min. / 1973 / Japan

NOON YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 3min. / 1976 / Japan

Observation YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 10min. / 1975 / Japan

epilogue YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 1 min. / 1976 / Japan

MOTION YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 10min. / 1980 / Japan

GEOGRAPHY YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 7min. / 1981 / Japan

[kei] 1991 YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / video / 13min. / 1991 / Japan

VISION TAKE 1 YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 8mm / 3min. / 1973 / Japan

VISION TAKE 3 YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 3min. / 1978 / Japan

HELIOGRAPHY YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 6min. / 1979 / Japan

WALKING WORKS YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 5min. / 1983 / Japan

3・・・ YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 5min. / 1984 / Japan

WINDS YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / 16mm / 6min. / 1985 / Japan

Sakura YAMAZAKI Hiroshi / video / 19min. / 1989 / Japan

The Seas of YAMAZAKI Hiroshi HAGIWARA Sakumi / digital / 20min. / 2018 / Japan.

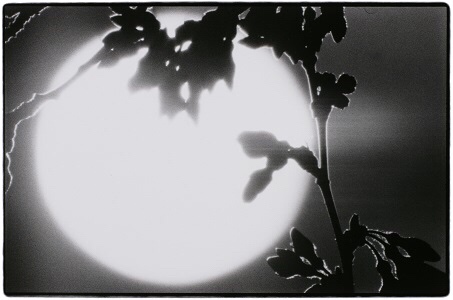

Among these works, three stood out for me. Observation (1975) is a ten-minute film, shot in 16mm, in which he created the illusion of twenty-eight suns arching over the sky in his neighborhood, and Sakura/Flowers in Space, shot on video in 1989, is a reflection on film of the ideas he captured in a series of photos towards the end of his career. Cherry blossoms are here depicted against the Sun, thus losing all the color and beauty they are usually associated with, and mutating instead into black shapeless figure of almost phantasmatic solitude.

But the absolute highlight was Heliography, a continuation but also a variation of what Yamazaki had being doing for more than 10 years with his photos, resulting in one of his most well known series, Heliography, released in 1974. In this series of photos of stunning visual impact Yamazaki subtracts all the unnecessary elements that usually are linked to a beautiful costal landscape, focusing primarily on the sun and the sea, captured here through very long exposures.

Seeing Heliography was for me almost a transcendental experience, and for a variety of different reasons. First of all because it came after an hour of seeing his short experiments in 8mm and 16mm, most of them interesting from a photographic point of view and in tracing a path in his oeuvre, but almost forgettable as stand alone works. Heliography arrived also as a natural progression of his experiments on film, but at the same time as a deviation and something completely new as well. It is visually and conceptually one of the most compelling films I have seen this year, six minutes of pure bliss. Like in La Région centrale, the oblique images of the Sun over the sea and the eye of the camera fixed and fixated on the star with everything else moving around, unanchor the viewers from the Earth, liberating and disengaging the vision from the human eye and re-centering it around the drifting Sun in what becomes in the end an astral landscape.

To add one more layer to the experience, I really believe that had I watched all the works at home on a TV, non matter how big, Heliography would not have retained the same majestic power, I know I’m stating the obvious here for most cinephiles, but certain type of experimental cinema should be absolutely seen in theater.

You must be logged in to post a comment.