A traveling retrospective dedicated to Isobe Shinya, one of the most interesting directors in the contemporary Japanese experimental film scene, was held in various cities in Japan in recent months (with more places and dates to come). At the end of June, the retrospective, 美しい時代錯誤 A Beautiful Anachronism, visited Nagoya Cinema Neu (formerly Nagoya Cinematheque), where I had the pleasure of meeting Isobe and attending a screening of five of his films made between 2009 and 2022. An excerpt of his new work, which is still in progress, was also screened.

A primary theme running through all of Isobe’s works is time—more specifically, the various temporalities and durations that the camera can capture and create. Isobe’s preferred film medium is 8 or 16 millimeters, but he almost always edits and works on his films digitally. The exceptions are Dance, shot and edited on film, and Humoresque, which was shot in digital.

His time-lapse and long exposure works capture extended periods of time and greatly accelerate the pace at which we usually experience it. This gives the viewers a sense of vertigo and a new perspective on things. It invites us to reconsider our position in the world, hinting at different times: seasonal, geological, astronomical.

The first film presented at the retrospective was Dance (2009), an assignment Isobe completed for the Film Research Institute as part of a class he was taking at the time. The six-minute short was shot in 8mm over the course of a week, with filming taking place for about five or six hours every night in a room where a girl was living. The room was dark, and the only source of light during the shooting came from the streetlights outside.

The altered and accelerated time of the work highlights the quasi-life of the objects in the room and offers an accumulation of personal memories—the young protagonist was Isobe’s girlfriend at the time and she would eventually become his wife (later seen in Humoresque).

Objects and ruins also play a central role in his next work, EDEN (2011), Isobe’s graduation project at Image Forum Film Institute. Filmed over the course of a year and a half, with monthly visits of three or four days, to the abandoned Matsuo mine complex (operating from 1914 to 1979) in Iwate Prefecture. The film captures the area’s decay and showcases how life moves forward when is freed from the anthropic element. The images and hypnotic music create the impression of a ghost village slowly being reclaimed by vegetation and slipping into (human) oblivion.

First, the camera focuses on the interiors of former miners’ and their families’ homes. Then, in time-lapse segments, the camera pans to the open spaces surrounding the village and the expanse of the sky. Isobe makes his work almost meta-cinematic by superimposing images of the mines within a room and including stop-motion shots reminiscent of Itō Takashi‘s work. These shots feature photographs of the area within frames of the ruins themselves. As with most of Isobe’s work, EDEN has a pivotal moment toward the end: a crescendo accompanied by a sudden burst of rock music when snow starts to slowly rise from the ground in reverse, with the crystals ascending to the sky.

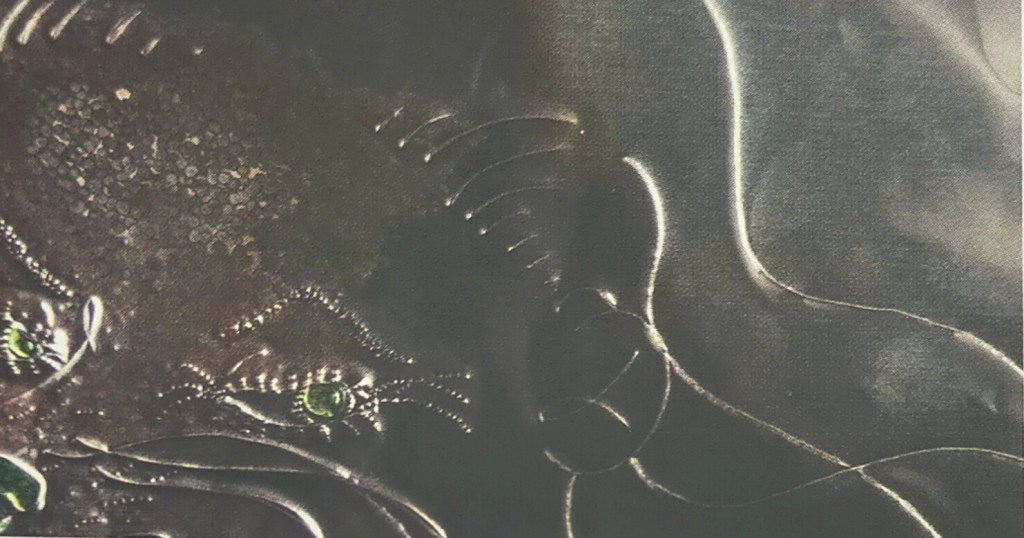

As you can see in the short clip posted below, music plays an important part in his next film too, For Rest (2017). Here Isobe shifts his focus to the decomposition of a set table in a forest. Filmed over five years with progressively longer intervals in the woods at the foot of Mount Fuji in Shizuoka Prefecture, the film documents the table’s decomposition and the gradual takeover by vegetation and insects. Isobe originally intended to film it in the Aokigahara Forest in Yamanashi; thus, the theme of death permeates the whole work. As Isobe stated, the film “contrasts the human tendency to separate and distance life and death from each other with the cycle of life in nature.”

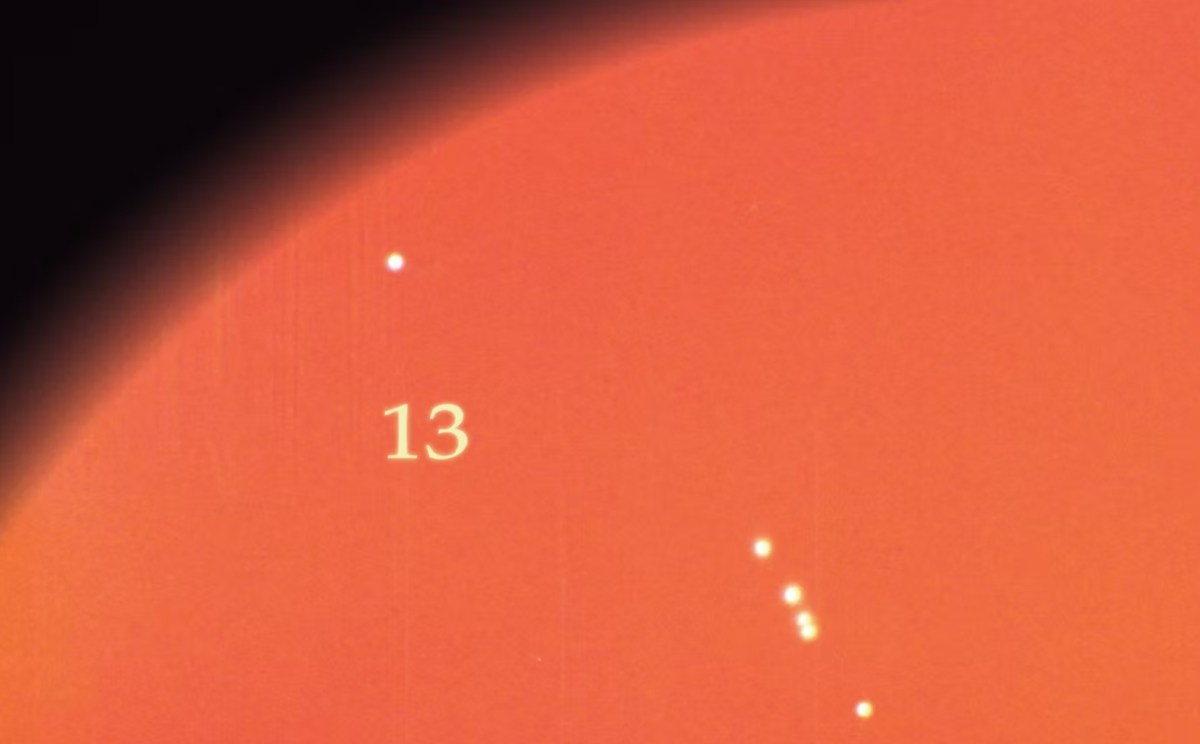

Even more distant from our everyday lives in scope is the cosmic time depicted in Isobe’s 2020 masterpiece, 13. This short film is composed of images of the sun captured at 13-second intervals from the same position over five years.

The result is a cosmic journey through time and space, but structurally confined from a fixed point of view, depicting the sun’s passage across the sky where light, time, and space beautifully converge to create an abstract calligraphy on a red and purple canvas.

I previously wrote about 13 here.

The final piece in the retrospective, Humoresque (2022), was also filmed over about five years. It is Isobe’s first work shot entirely digitally, marking a departure from his previous works. It is different also in that the subject is in this case his family: his wife and young son. What impressed me most about Humoresque was the subtle play and experimentation with sound. All of the sounds were added in post-production (I think); this is the first time Isobe has worked with sound distortion rather than time distortion. The result is a playful, powerful, and subtly experimental home movie of sorts.

Isobe is currently shooting his next film. The provisional title is April, so it was introduced, although he said it might change. An excerpt was screened at the retrospective, and from the few minutes shown, it appears to be composed of images of rivers, water, and other natural elements overlapping. It looks really promising.

You must be logged in to post a comment.