Third part (you can read the first part here and second here)

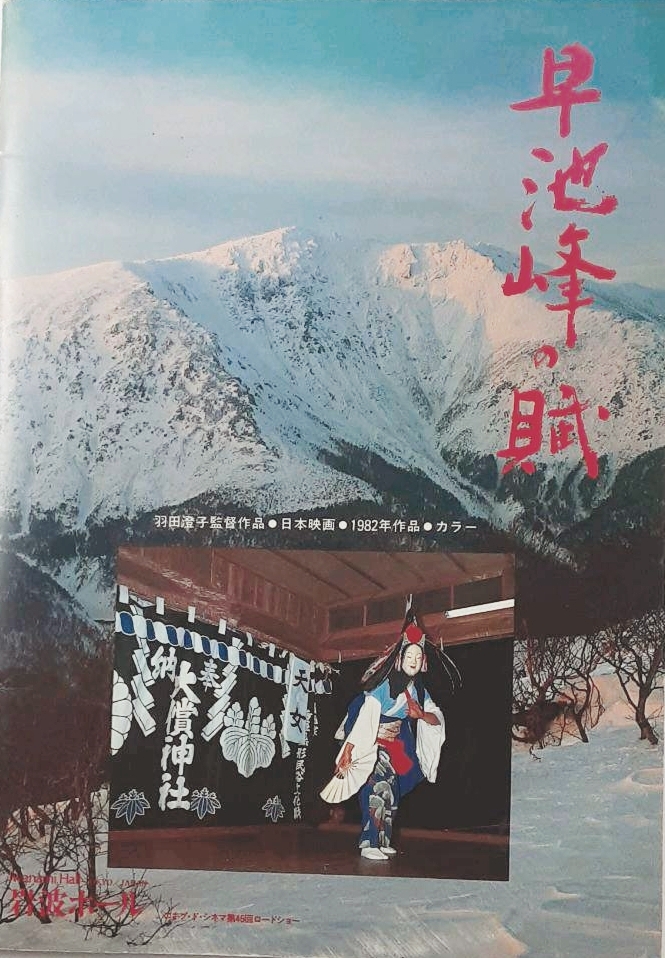

A slightly different post today, since it’s not about Haneda Sumiko’s own writings, but more about one of Haneda’s documentary, and one of the most significant in her career, Ode to Mt. Hayachine 早池峰の賦 (a.k.a. The Poem of Hayachine Valley). The movie was released in 1982 at the Iwanami Hall, distributed by Equipe de Cinema, where it stayed from May 29th to June 25th (and later from August 7th to 13th). A booklet about Haneda and the movie was published and sold at the theater, in it there are various writings by Haneda, Tsuchimoto Noriaki, people of the village in Iwate, and Paulo Rocha, among others. The Portuguese director, with whom Haneda collaborated as a screenwriter for a segment of his A Ilha dos Amores (released at the Iwanami Hall in December 1983), wrote an interesting piece on Ode to Mt. Hayachine; you can read my translation below (NOTE: This is by no means a professional translation, but I hope the readers can get the gist of it):

Paulo Rocha on Ode to Mt. Hayachine

In an Italian film similar to this one, L’albero degli zoccoli / The Tree of Wooden Clogs, director Ermanno Olmi told us, with rare insight, about the heart and the inner world of Italian peasants. Haneda goes here even further, for her, it is not only the heart of the people who speaks in her movie, but it is as the whole of nature, trees and stones, were speaking to us. Although we are in 1982, immersed in our contemporary problems, at the same time, we live with simplicity in an uncomplicated world that has just been created right now. There is a difference between Olmi and Haneda, and it may be a difference that exists between a country with a Catholic tradition and a country with a Shinto tradition, but still there is a miracle that is common to the two. This miracle is that in their clear mind everything is sublimated and yet, a direct and spontaneous force, an inspiration and a beauty in the detachment of modern daily life is gradually invading our hearts. For Haneda, the mountain gods, the plastic products in the small shops in the village, the people who dance the kagura, and the tourists are just as passionate and fantastic. Everything is just as important to her non-sentimental gaze. That is, past and future, nature and machinery, mountains and towns. What is art for, what is fiction for, what position does the profilmic material occupy in a movie, what position does fiction occupy in art? What about the artist? What happens to the artists filmed? Rarely in the history of cinema have such essential questions been asked in such a direct, simple, generous, and intelligent way. I am a filmmaker, and until now I believed that I would be closer to the truth if I approached it through fiction, but now, after seeing Haneda’s Ode to Mt. Hayachine, I realize that the idea is an arrogant one, we must take advantage of this opportunity, we must learn to see reality correctly in order to know the truth. Ode to Mt. Hayachine gave us the best example of this. In Europe, documentary films are being re-evaluated as part of a movement for a new type of cinema. If Ode to Mt. Hayachine were to be introduced in Europe, they would no doubt be surprised and respectful to find that the path they were looking for already existed in Japan. Centuries from now, when people in the future will want to know what we were like, they will be able to watch Ode to Mt. Hayachine, and the movie will tell them about us, the audience of the film today, and about little-known people who were lost among the mountains, in an unknown valley.