As usual, the list below is a reflection of my taste, interests, and viewing habits during 2021, this year mainly, but not exclusively, online. I’m not sure all the titles can be considered documentaries, but this is, after all, the fascinating beauty of dealing with documentary cinema. Synopsys in italics, followed by my quick take and, when available, the trailer:

Kanarta – Alive in Dreams (Ōta Akimi). Sebastian and Pastora live in a Shuar village in the upper Amazonia of Ecuador. Sebastian is not only a respected healer, but also a medicinal botanist who experiments with unknown plants he encounters in the forest. His unique practice seeks to cultivate new knowledge, reconnecting him with his ancestors. Pastora is one of the rare female leaders in Amazonia, who struggles to negotiate with local authorities for her community. With powerful plants such as ayahuasca, they revive and energise their perceptions of the future. These plants allow them to acquire power and a faith to cope with the obstacles they now face, given that their lives have been irreversibly affected by the modern state system. There is a lot to like about this movie, and, like in the best works that cross the boundaries between documentary, visual anthropology and experimental cinema, every new viewing reveals extra layers. On the one hand Kanarta shows the problems Shuar people and their culture encounter in dealing with modern society and the way their community adapts and changes in response. On the other, it also offers a glimpse of their being part, almost as if made by the same flesh, of the Amazon forest, and their vital connection with the medicinal plants, “plants that make reality” as one of the people suggests.

However, what really kept me engaged throughout the whole movie is that the documentary is permeated by joy, there are lots of laughs and funny scenes, usually fuelled by chicha, an alcoholic beverage made of fermented potatoes. The joy is also coming from the movie and its protagonists being in a constant state of exploration, through the visions and through the wandering in the forest in search for new plants or new places where to build a house. Kanarta offers also some emotional and even dramatic scenes, it’s very touching for instance, when we see Sebastian’s son receiving his medical diploma during a small ceremony, and father and mother posing with him for the camera with pride and smiles. This contributes to build a stronger sense of attachment for the two protagonists, Sebastian and Pastora, who are willing to show and tell the director about their culture and their way of living.

The main reason why everything works though—from the more poetic scenes, to the more visceral ones, when Sebastian takes ayahuasca for instance—is because the documentary is structured in a dialogic manner, so to speak. The camera is not a passive actor in the scenes, but it’s part of, and often influences, what is going on, directly or indirectly. Furthermore, Ōta is very good at transmitting, through an immersive visual and sensorial experience, the powerful feeling of empathy that emanates from Sebastian and Pastora, and the Amazon forest itself.

.

13 (Isobe Shinya) The filmmaker left his camera in exactly the same spot for five years to shoot a picture of the sunset every thirteen seconds. In a series of merged time-lapses, we see the sun(s) moving repeatedly from the left part of the screen to the right. One of the best movies I’ve seen this year, documentary or not, I wrote about it here.

.

Inside The Red Brick Wall (Hong Kong Documentary Filmmakers) On 17 November 2019, the police laid siege to protestors at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University in a blockade lasting nearly two weeks. Beleaguered students fought teargas with makeshift whiteboard shields, hoping to escape and return home to safety. With the media barred from on-site access, an anonymous collective films from within the campus, recording the teenage protesters’ hopes and distress. From the very first shot the documentary is imbued with a sense of precariousness and anger, and by filming the violence between riot police, students, aid people, and members of the press —mainly independent press that live-streamed the battles on the internet— captures and creates, through a masterful use of editing, a very powerful sense of space and proximity with the students, a visual cartography of violence and resistance. The scenes when many of the young students break down, cry and walk out, defeated, from the campus, often criticized by their comrades, is— although it is something I have seen over and over again in the documentaries about the Japanese protests of the 1960s and 1970s—heartbreaking. What is also extremely fascinating for me, is that all the young people wearing masks and gear, for protection and for anonymity, form, more than a revolt of the individuals, a resistance of the multitude. The sense that the struggle is about something bigger than the siege itself is very palpable.

.

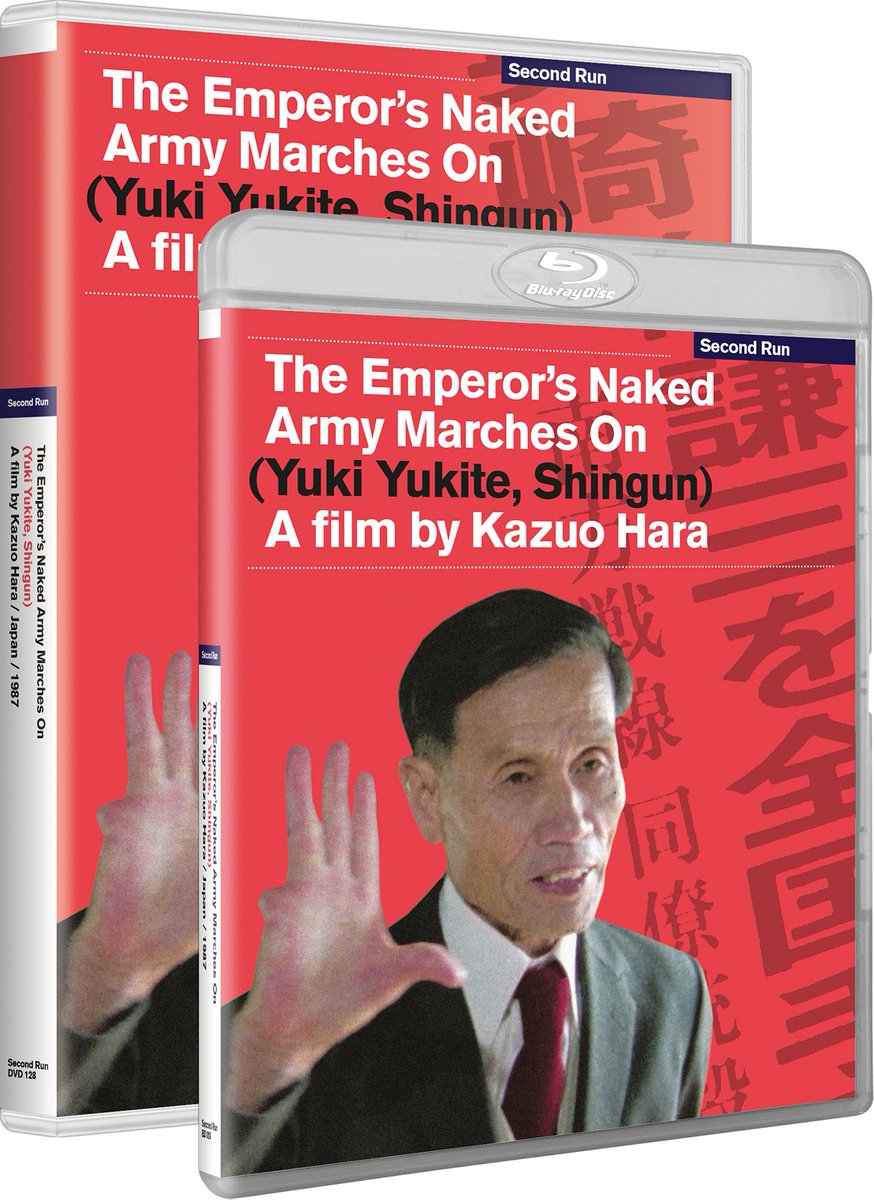

Minamata Mandala (Hara Kazuo) After years of dumping industrial wastes from the factory to the ocean, Chissō Chemical Corporation contaminated the area of a small Japanese fishing village with excessive amounts of methylmercury. This highly toxic chemical bioaccumulated in fishes of the local water, which when consumed by the local populace resulted in mercury poisoning. In 1977, Minamata disease certification criteria was set by a strange method that tried not to recognize the rights of environmental disease patients. However, an Osaka court won the case for some patients because of a newly developed theory by medical doctors’ recent experiments and proofs. For decades, these patients struggled within the Japanese judicial system for their rights to receive compensation as victims of environmental disease. Those different aspects of these patients’ lives have been filmed by director Hara for the last 15 years, inspired by the late director Tsuchimoto’s documentary MINAMATA: THE VICTIMS AND THEIR WORLD (1971). Not a minute of the documentary (it’s 373′ long) is superfluous. This is, in my view, one of Hara’s best works, and so far the pinnacle of the second part of his career as a filmmaker.

.

The Works and Days (of Tayoko Shiojiri in the Shiotani Basin) (C.W. Winter, Anders Edström) An eight-hour fiction shot for a total of twenty-seven weeks, over a period of fourteen months, in a village population forty-seven in the mountains of Kyoto Prefecture, Japan. It is a geographic description of the work and non-work of a farmer. A portrait, over five seasons, of a family, of a terrain, of a soundscape, and of duration itself. Undeniably it’s an impressive cinematic achievement and is worth engaging with it, but for me, once the “artificiality” of the movie becomes apparent, it loses part of the appeal and power. I’m not revealing more to avoid spoilers (but are there really spoilers?). Also, I’m approaching the movie from a special angle: I live in Japan, in a somehow similar place to the one depicted in the film.

All that being said, the soundscape is astounding, and I like how the movie’s editing is often constructed following the sounds. I really should, and I wish to one day, experience it in a theater.

.

Soup and Ideology (Yang Yong-hi) Confronting half of her mother’s life—her mother who had survived the Jeju April 3 Incident—the director tries to scoop out disappearing memories. A tale of family, which carries on from Dear Pyongyang, carving out the cruelty of history, and questioning the precarious existence of the nation-state. With her latest documentary Yang Yonghi continues to explore how her own personal life is tragically connected to the post war history of Japan and Korea. The movie presents not only the painful memories of the Jeju massacre (April 3rd 1948) as remembered by the director’s mother, and the destruction a family, her three brothers were sent from Japan to North Korea at a young age, but it is also an emotional portrait of her frail and ageing mother. As the film progresses she is diagnosed with senile dementia, and little by little she loses her memories, including those of the massacre she witnessed, only 18, in the small Korean island. The movie is also partly an act of self-reflection by Yang Yonghi herself, if in the first part she is the one filming her mother, and we don’t really see her too much, in the second, when her mother condition worsens, she enters the frame more often, and becomes the co-protagonist of the film. We can clearly see her emotions, especially when she visits the island, with mother and husband, for the anniversary of the massacre. There, Yang Yonghi understands that her mother’s affiliation and attraction for North Korea, something the director had never completely forgiven her for, was also caused by the atrocities committed by the South Korean Army her mother saw with her own eyes.

It would have been a better movie for me, had not been for the five or so minutes of animation used to explain her mother story in Jeju in 1948. I found the segment out of place and it really took me out of the movie.

.

Shiver (Toyoda Toshiaki) A music movie featuring a performance of Taiko Performing Arts Ensemble ‘Kodo’ and Koshiro Hino. Filmed entirely on Sado island. Partly a filmed music performance, partly a visual experiment connecting music, landscape and spirituality, Shiver is a fascinating piece of work that fits perfectly with what Toyoda has being creating in recent years. Through the spiritual encounter between Sado landscape and the hypnotic music of the taiko drummers, Toyoda touches and expands some of the themes tackled in some of his most recent films, such as the The Blood of Rebirth, Monsters Club, and The Day of Destruction. That is, the primal nature of the world we inhabit, and how we, humans, can connect with it through music, a similar approach was also at the core of Planetist in 2020. Something primal not in a temporal sense as something that comes before, or ancestral, but more as something essential that is always present and awaits to be discovered and brought to light. Like the rock/monolith towards the end of the work, which seems to have some kind of energy inside, and whose light is filtering through the cracks only when the music plays.

.

Whiplash of the Dead (Daishima Haruhiko) Weaving together the memories of Yamazaki Hiroaki, a university student who lost his life in the First Haneda Struggle in 1967 through the words of his bereaved family and ex-classmates, this film turns the memories of those who protested against government power into questions for the future. The movie is comprised of two parts, for a total of 200 minutes, in the first 90 minutes the director focuses on the events preceding the death of Yamazaki, while in the second segment, that could easily have been another movie, the protagonists of the students protests of the late 1960s, reflect on the reasons of the implosion of the new left and its movements.

The story of the Mito family, not affiliated with any left group, but a family that helped the young people in prison, and later promoted anti-nuclear activism and whose members (father and two sons) tragically died in 1986 in a mountain incident, is so fascinating that would deserve its own documentary.

.

Discovery of the year: Alchemy (Nakai Tsuneo, 1971). The camera slowly zooms, in over a long period of time, on the light of the sun reflected in the mirror of a bicycle parked at the construction site. To this is added a slowly evolving flicker effect derived from negative-positive reversals, progressively dismantling the distance from the subject. Nakai created a masking film with a calculated pattern of black and white frames into which he inserted positive and negative images and made a print out of two separate rolls of film. The original projection speed was 16 frames per second, but the sound is separate from the open-roll tape rather than burned in, so it can also be screened at 24fps. Also, the original sound consisted of the friction noise of rubbing steel, but in 2019 a new version of the sound was created featuring the friction noise of glass. Two versions of the film exist: 24:15 mins at 24 fps and 40 mins at 16 fps. A structuralist film made in 1971 by Nakai, clearly inspired by Michael Snow’s Wavelength, but at the same time highly original, and somehow anticipating Matsumoto’s Atman.

.

Honourable mentions: Her Socialist Smile (John Gianvito), Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Questlove)

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

Before digging into this fascinating trip through the history of Japanese non-fiction film, let me add some overall thoughts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.