Both for their importance in the history of Japanese documentary, and for their intrinsic artistic value, the two films below would deserve a longer and deeper analysis, but time is always scarce here… perhaps in the future…

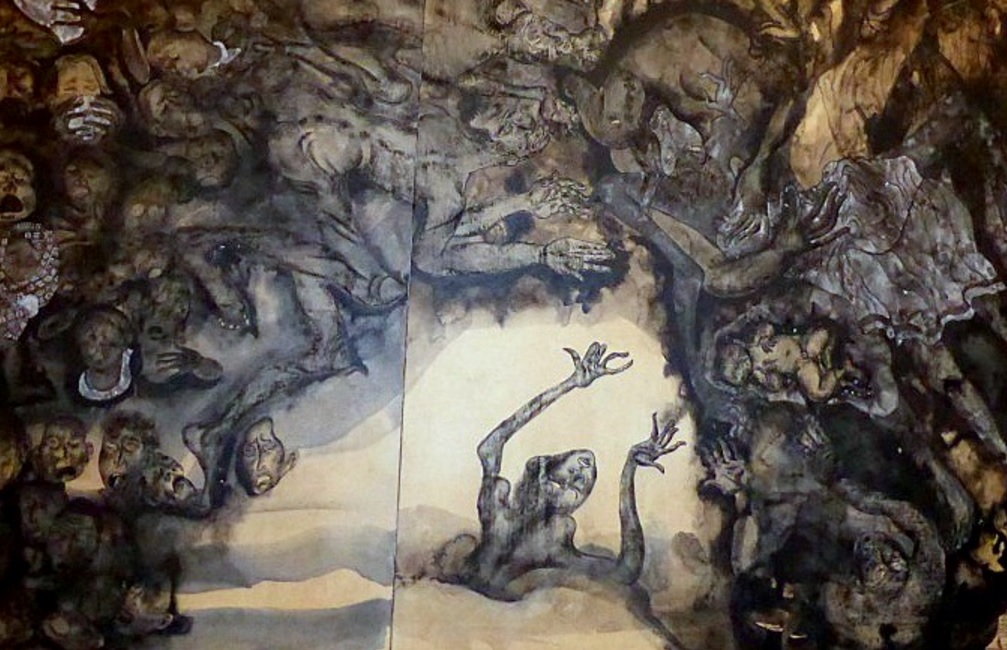

For some reason, in my exploration of the documentaries made during his long career by Tsuchimoto Noriaki about the Minamata disease and its victims, The Minamata Mural (1981) completely escaped me, at least until now. The film asks the delicate question of how it is possible to represent and depict the suffering and the struggles of Minamata’s victims, and more broadly, how artists can express, through their medium of choice, the sorrow caused by other tragedies as well, such as the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or the suffering inflicted to minority groups in Japan.

Tsuchimoto and his crew follow Maruki Iri and Akamatsu Toshiko, a couple of artists working on a series of panels dedicated to the people of Minamata, showing us the couple at work on the mural, and during their visits in Kyūshū, when they meet some of the people affected by the disease. By showing how these encounters, especially with two young girls, influenced and changed the perspective of the two artists, Tsuchimoto is also, subtly but obviously, reflecting on his own (at the time) decade-long endeavour in capturing and siding with the people in Minamata.

The segment around the middle of the film, when activist and writer Ishimure Michiko reads her poems over the close-ups of the huge mural, is a spine-chilling and heart-wrenching masterpiece of a sequence. For me, one of the most impressive qualities of the scene, besides the poetic words by Ishimure, is how powerfully the camera is able to convey the intensity of the paintings.

Another striking aspect of the documentary is how Tsuchimoto and his cameramen are able to capture and convey on film the beauty of the young people affected by the disease. Shiranui Sea (1975), probably the peak of Tsuchimoto’s career, has a balance and a grace in depicting the people of Minamata, particularly the young ones, that can be found here as well.

One of the two cameramen in The Minamata Mural is Segawa Jun’ichi, a director of photography who, among other films, worked in the seminal Snow Trail—directed by Taniguchi Senkichi in 1947, from a script by Kurosawa Akira, and starring Mifune Toshirō in its first role—and with Haneda Sumiko in Ode to Mt. Hayachine— he was mainly in charge of filming the mountains—a documentary filmed around the same period as the one here discussed. It would be interesting to know if Segawa shot the paintings, was involved in filming the people and scenery in Minamata, or was involved in both (I’m inclined to think it’s the former).

“This linking of memories, this setting remembrances in motion, is not a nostalgia but an immanence,”

Crisca Bierwert

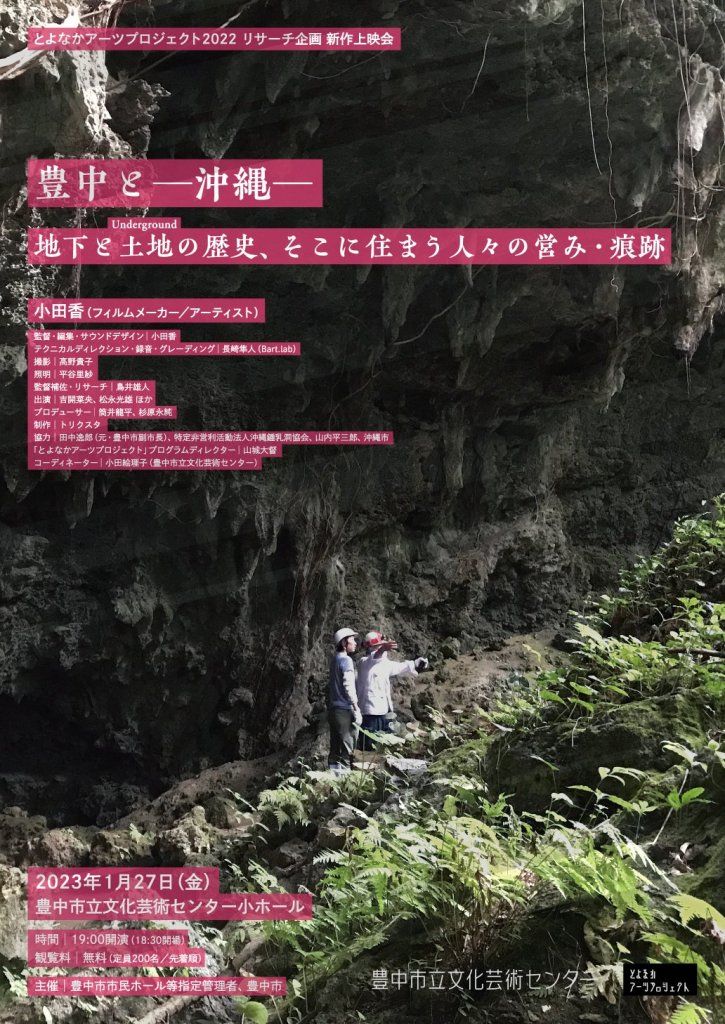

A Grasscutter’s Tale (1986) is one of the Japanese “documentary treasures” I have been meaning to watch for quite a long time. The occasion finally came last April, when it was screened at Athénée Français Cultural Center in Tokyo, part of a very interesting retrospective about resistance and political struggle on film, organised to launch the new documentary by Daishima Haruhiko, Gewalto no mori – kare wa Waseda de shinda (ゲバルトの杜 彼は早稲田で死んだ, 2024).

The film focuses on grandma Someya, born in 1899, one of the farmers who lived and worked on the land to-be-expropriated for the construction of Narita Airport. She fiercely opposed the second phase of the airport, a stance that severed her relationship with her family, and resulted in her living alone on her land. The film consists of nineteen stories narrated by grandma Someya’s own words, and mainly of images of the old lady cleaning her field.

Part of the Sanrizuka notes Fukuda Katsuhiko (1943-1998) took after he left Ogawa Production at the end of the 1970s, after the collective left for Yamagata, the film is a crucial work to better understand the history and development of documentary practices in Japan, in that it heralds a shift in the way documentary was conceived, theorised and practiced in the archipelago. The film occupies at least two spaces: militant cinema with a focus on the resistance of one person (Someya-san) against the construction of Narita Airport on the one side, and a mode of cinema that explores the different (hi)stories traversing a physical space, Sanrizuka, and how these intersect with the personal history of one individual. Moreover, seen from a different perspective, A Grasscutter’s Tale can also be considered as an example of “oral cinema”, that is, a cinema that connects and activates the untapped potential of storytelling and the spoken word in relation with the moving image. By combining images and tales that are parallel and do not touch each other, so to speak—as previously noted, the images show mainly Someya-san working on her field—the film constructs a segmented and open portrait of a life, a poetic bricolage made of stories and images that invites the viewers to wander inside of this personal/historical “landscape”.

The film has an episodic structure and is composed of chapters, some funny and some tragic, such as the story of her sons who died, her husband who worked as barber, a strange dream remembered, the time she first came to Sanrizuka, or how she once ate only matches as a child to avoid starvation. Sometimes A Grasscutter’s Tale edges towards the experimental. In the segment about the dream, the screen is completely dark except a bright light on the upper left corner, in another, the voice of the director explain (if I’m not wrong) again on a black screen, how the reenactment of an episode from the old lady’s life was scrapped from the final work at the request of her son, who was in it.

The screening I attended was in 16mm, a rare chance to better appreciate the colours and the texture of the work. The greens of the crops and of the grass are almost tactile, and the time-lapse scene of the setting Sun, here a fiery red, is akin to that in Magino Village, a very different film, but a work that nonetheless shares many common traits with A Grasscutter’s Tale.

You must be logged in to post a comment.