This is my final piece on this year’s Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival. It comes very late, apologies, it’s been a busy time.

Previous reports:

YIDFF 2025: preview

report 1: SPI (Sayun Simung)

report 2: Awards

report 3: From the River to the Sea, and the Mountains: Filmmakers in Solidarity with Palestine – A Gathering

report 4: Appalachian Lenses, Hakishka

report 5: The Future of Dialogue: Yoshida Dormitory, Kyoto University

Heta village and the surrounding area, together with the people who lived there, are at the center of one of Ogawa Productions’ masterpieces—and the final work the collective shot before relocating to Yamagata—Narita: Heta Village (1973). About two decades ago, when the few remaining inhabitants were relocated, the area became a ghost of its past, a past that is threatened to be erased in the coming years with the further planned expansion of Narita Airport. This will cause the partial submersion of the zone, wiping out hundreds of years of culture, traditions, collective and personal memories, and not least, resistance.

After moving to Yamagata in the mid-1970s and after the death of Ogawa Shinsuke in 1992, the collective left behind a massive quantity of unused audiovisual material and notes—Ogawa also left a huge debt, though that is another story.

The Hokusō Regional Materials and Cultural Assets Preservation Network is a volunteer organization established in 2024 to document and preserve the buildings, communities, memories and landscapes that will be lost as a result of the large-scale expansion work currently underway at Narita Airport. One of the areas greatly affected by this expansion is Shibayama Town, where Heta Village was filmed. As part of its activities, in September 2024 the network co-organized Heta Project, a workshop for filmmakers and artists to engage with the material left by Ogawa Pro and create audiovisual works that reflect on the landscape of the area and the memories connected to it.

The results of this workshop were screened at one of the satellite events held in Yamagata on October 13, Sanrizuka: Disappearing Landscapes—The Heta Project Screening. Six short films were presented, and most of the filmmakers were also at the venue to discuss their work.

What I found particularly fascinating was the heterogeneity of the participants—not only in age and nationality, but also in their levels of knowledge about Ogawa Productions, and the history of the area. Some, like Markus Nornes, have been writing and speaking about the documentaries and the resistance of its people for decades; for others, this project served as an entry point to discover the films and to become familiar with the issues affecting the region. The following films were screened:

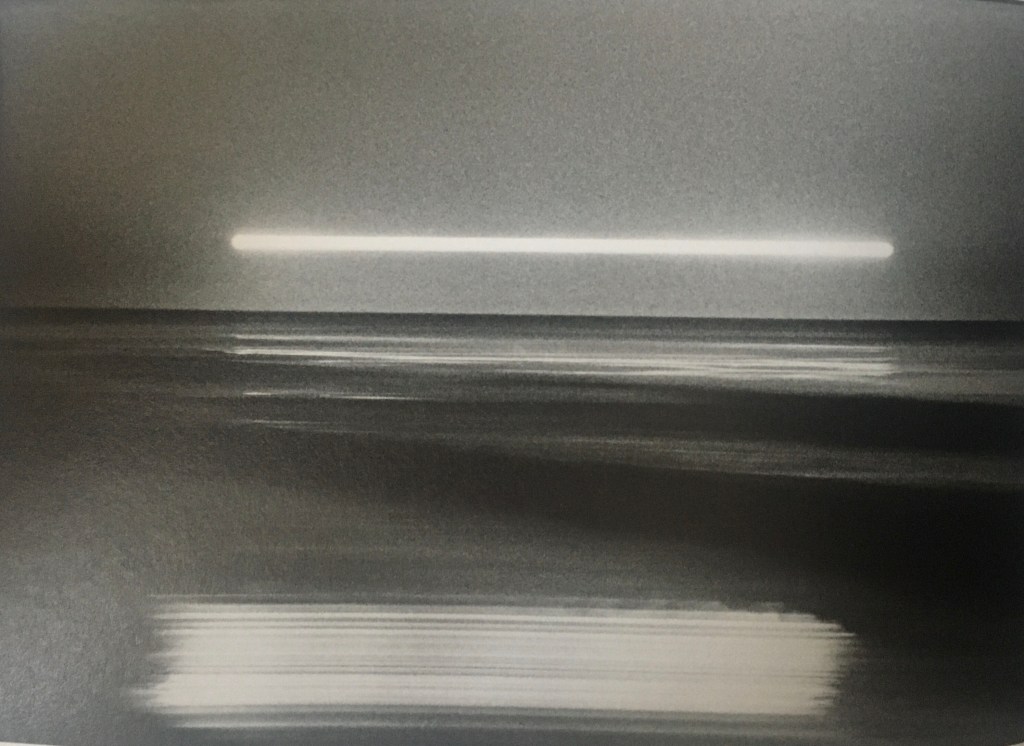

三里塚ー辺田部落の時間 Sanrizuka—Village Time in Heta Village (Markus Nornes, 2024), 13′.

抵抗のむら The Village of Resistance (Stella Lansill, 2024), 5′.

此処に轟くThis ROAR Here…(Tanabe Yuma, 2024), 9′.

辺田部落へ To Heta Village (Watanuki Takaya, 2024), 10′.

三里塚 シャドー Sanrizuka Shadows (Wang Yijean, 2024), 6′.

辺田部落 瞑想 (祈)Heta Buraku Meditation (Prayer) (Aldo Schwartz, 2024) 12′.

The fact that Ogawa Production’s footage is freely available for artistic and historical purposes is an extraordinary achievement, and it could mark a turning point in the production of archival and compilation films in Japan. As I have already noted in a preliminary study on the subject, this form of cinema is strikingly absent from the Japanese audiovisual landscape—not only within the documentary sphere, but also in the experimental field.

One can only hope that this incredibly rich archive—there is, for instance, a great deal of vibrant color footage of natural elements and animal life, and the very fact that the collective chose not to use it says much about what they were striving for—will finally enter into circulation.

Beyond opening new artistic possibilities for filmmakers—Satō Makoto’s Memories of Agano (2004) is a shining example that pointed in this direction already two decades ago, and if I am not mistaken some of his peers are now moving along similar lines—the archive may also function as a living repository of Sanrizuka: its memories, its struggles, its history.

You must be logged in to post a comment.