This is a translation and a partial rewriting of a piece I wrote for Alias (Saturday supplement of the Italian newspaper Il Manifesto) in 2021.

In 2003, Māori director and theorist Barry Barclay proposed the idea of a “Fourth Cinema.” Building on and expanding the concept of “Third Cinema” as theorized by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in the late 1960s, Fourth Cinema designates a practice centered on the Indigenous gaze and Indigenous viewers. Rooted in Barclay’s background in documentary, the concept was initially conceived as an audiovisual practice in non-fiction—works created by Indigenous authors, within Indigenous communities, and for Indigenous audiences.

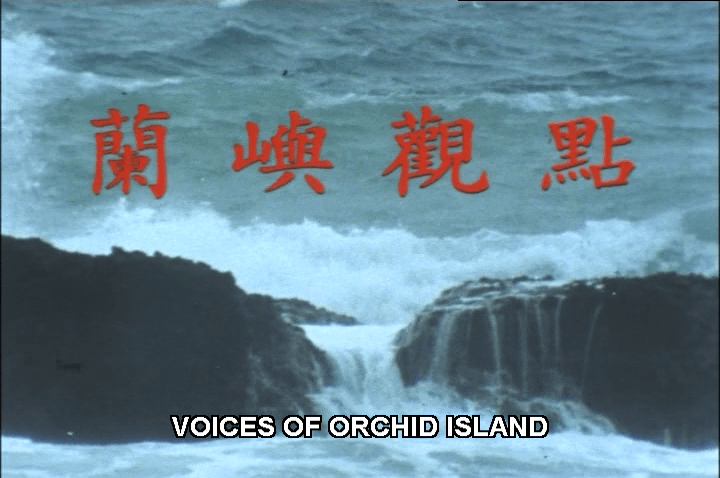

Paying homage to Barclay’s reflections, the twelfth edition of the Taiwan International Documentary Festival devoted a section of its official program to works by Indigenous filmmakers from the island, produced in the final years of the twentieth century (1994-2000). This was a period when long-standing questions of indigenous identity, resistance, and decolonisation converged with—and were amplified by—the revolutionary arrival of small, portable digital video cameras.

This technological shift, coupled with a transformed socio-political landscape, opened new avenues of self-expression for ethnic groups who, until then, had been confined to the roles of mere actors or spectators in their own representation.

It is worth noting that this followed the profound transformations of the last two decades of the 20th century—a period of seismic historical change for Taiwan, beginning with the lifting of martial law in 1987 and the subsequent democratisation of the country. On a cinematic level, this era also witnessed the rise of the Taiwanese New Wave and, on a smaller scale, the emergence of a grassroots documentary movement exemplified by the Green Team.

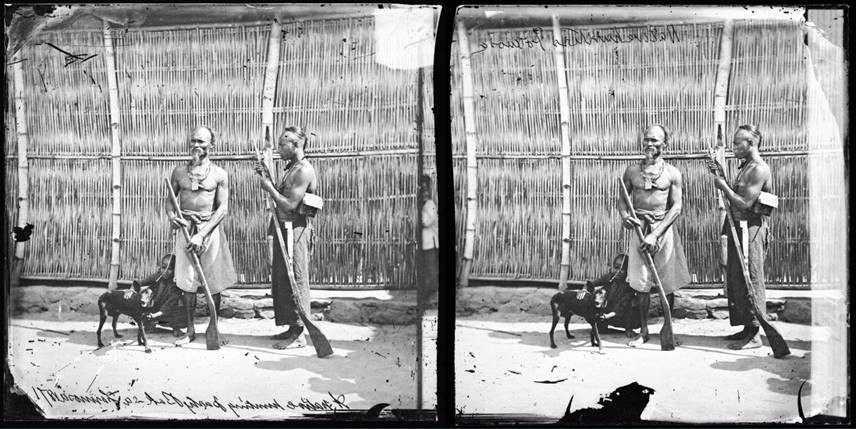

The history of Taiwan is one of centuries-long colonial domination. Its arts, customs, traditions, land, language, and landscape all bear traces of the successive layers of a history that, accumulating over time, have shaped the island as we know it today. The various Indigenous peoples who inhabited Taiwan for millennia first faced invasions by the Dutch and the Spanish, followed by the arrival of Han Chinese settlers from the mainland, and later domination under the Qing dynasty and the Japanese Empire.

Today, the island officially recognizes sixteen Indigenous groups, each with its own language and distinct culture. In most cases, these communities—despite enduring countless challenges—continue to strive to keep their rituals, languages, and traditions alive and meaningful, upholding alternative ways of life in resistance to the cultural homogenization brought by modernity.

By the late 1990s, the advent of digital cinema and the spread of small, affordable video cameras—“a theology of liberation,” to borrow a striking expression from Filipino director Lav Diaz—offered Taiwan’s Indigenous groups the possibility, finally and for the first time, of becoming active agents in their own visual representation, adding their voices to the island’s rich mediascape.

Indigenous with a Capital ‘I’: Indigenous Documentaries from 1994 to 2000 brings together seventeen works—each between thirty and fifty minutes in length—made by Indigenous filmmakers, focusing on the lives, struggles, and resilience of their communities in contemporary Taiwan.

In New Paradise (1999) by Laway Talay, members of the Pangcah ethnic group leave their ancestral lands to seek work in other parts of the island, only to encounter exploitation and a profound sense of non-belonging—perhaps the most recurrent theme running through the works featured in this special program. This feeling of displacement is often subtle, but at times it emerges openly and even defiantly, as in C’roh Is Our Name (1997) by Mayaw Biho, a short documentary that follows a regatta annually organized by Taiwan’s Han population—the ethnic majority of Chinese origin that constitutes most of the island’s inhabitants. For the first time in the competition’s history, a group of Pangcah—who had traditionally lent their nautical skills to other teams—chose instead to form a team composed entirely of their own members.

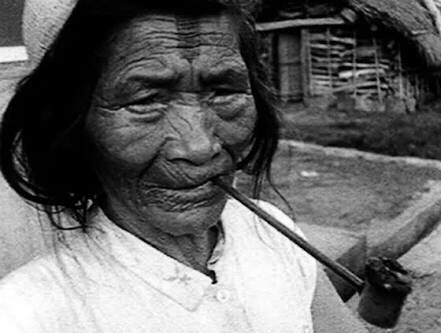

For members of these communities, holding a camera also means gaining the ability to recount and preserve ancestral traditions and forms of knowledge that might otherwise vanish with the passing of time. This is the case in several works devoted to capturing the memories of elders—such as former tribal chiefs or weavers—who embody the living memory of their people.

One of the most compelling works presented at the festival is Children in Heaven (1997), also by Mayaw Biho. Although it focuses on a specific ethnic group, the situation it portrays is, sadly, all too familiar in contexts marked by stark economic inequality. For a time, a small Pangcah community was forced to watch, year after year, as the government demolished the shacks they called home, deemed illegal structures. Surrounded by garbage and ruins, the children who grew up amid this Sisyphean cycle of demolition and rebuilding came to transform the recurring tragedy into a kind of game.

In this film, as in all the others in the program, the camera’s perspective is never detached or neutral. Aesthetically and narratively, it knows—and shows—from the very first scenes where it stands. The images are often low-resolution and deliberately anti-spectacular—what Hito Steyerl would call a “poor image.” It is a gaze that, precisely because it comes from within, does not judge—even when, as in Song of the Wanderer (1996) by Yang Ming-hui, it exposes the problems, contradictions, and even the violence that many of these communities face. Instead, it offers both a perspective and a means of expression to those who, until now, have had none.

You must be logged in to post a comment.