Today, October 21st, the National Film Archive of Japan organized a special screening of four films by Yamazaki Hiroshi, and 山崎博の海 The Seas of Yamazaki Hiroshi (2018), a short movie about the filmmaker and photographer, made by his friend and colleague Hagiwara Sakumi.

The screening was part of the series of exhibitions and events connected to the T3 PHOTO FESTIVAL TOKYO 2023.

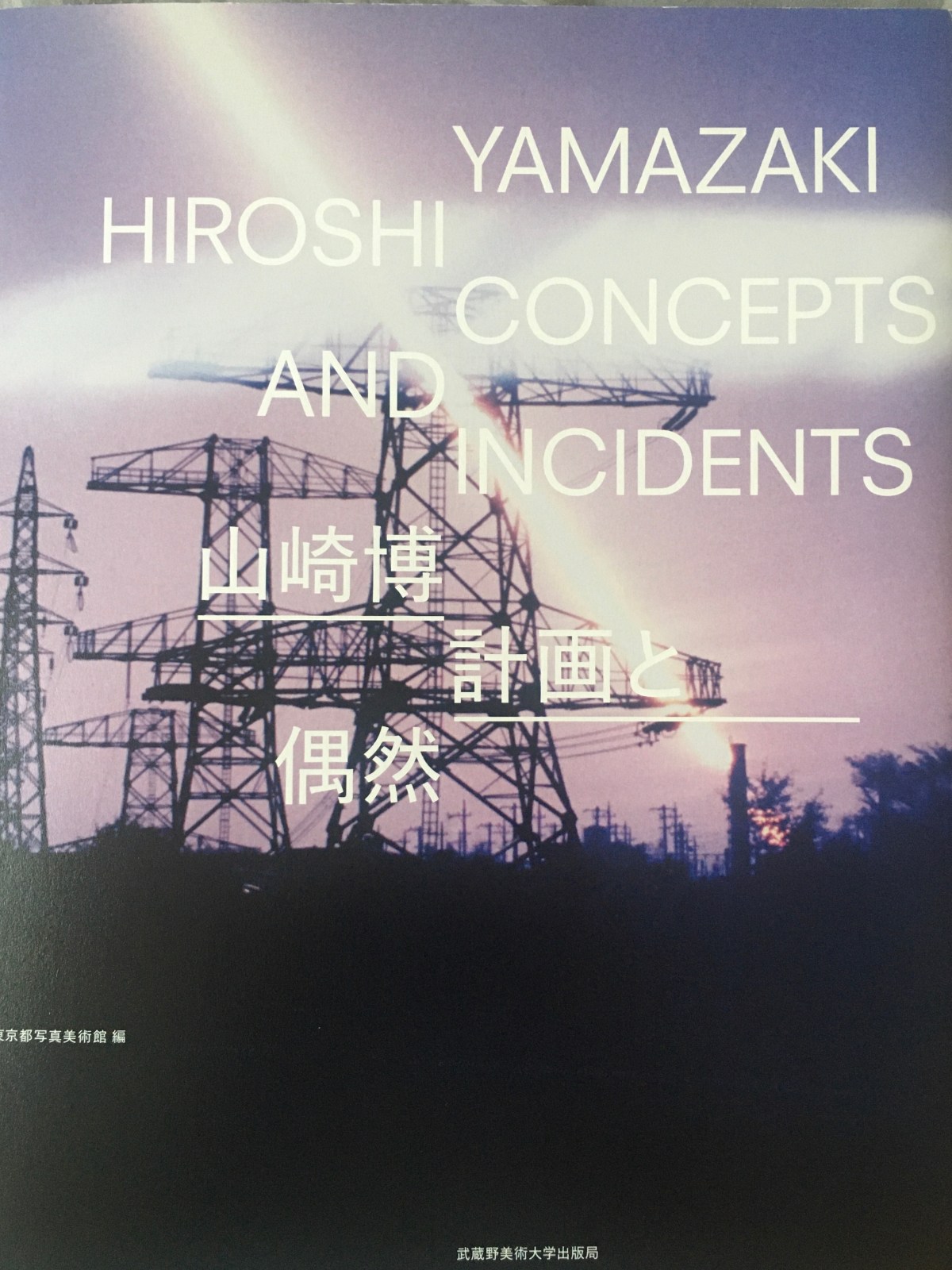

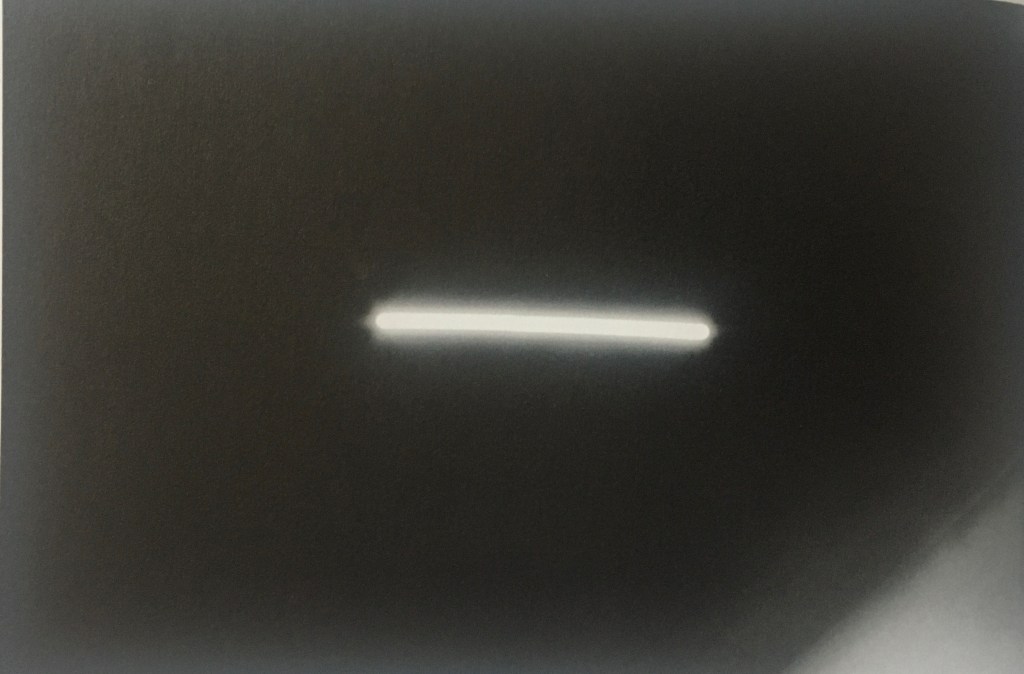

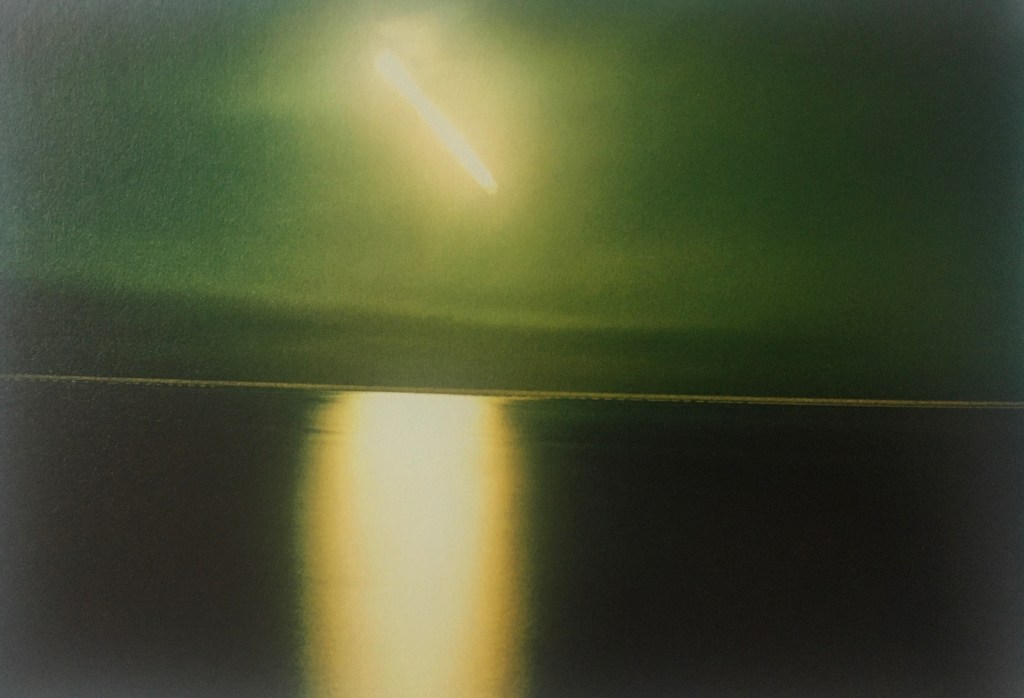

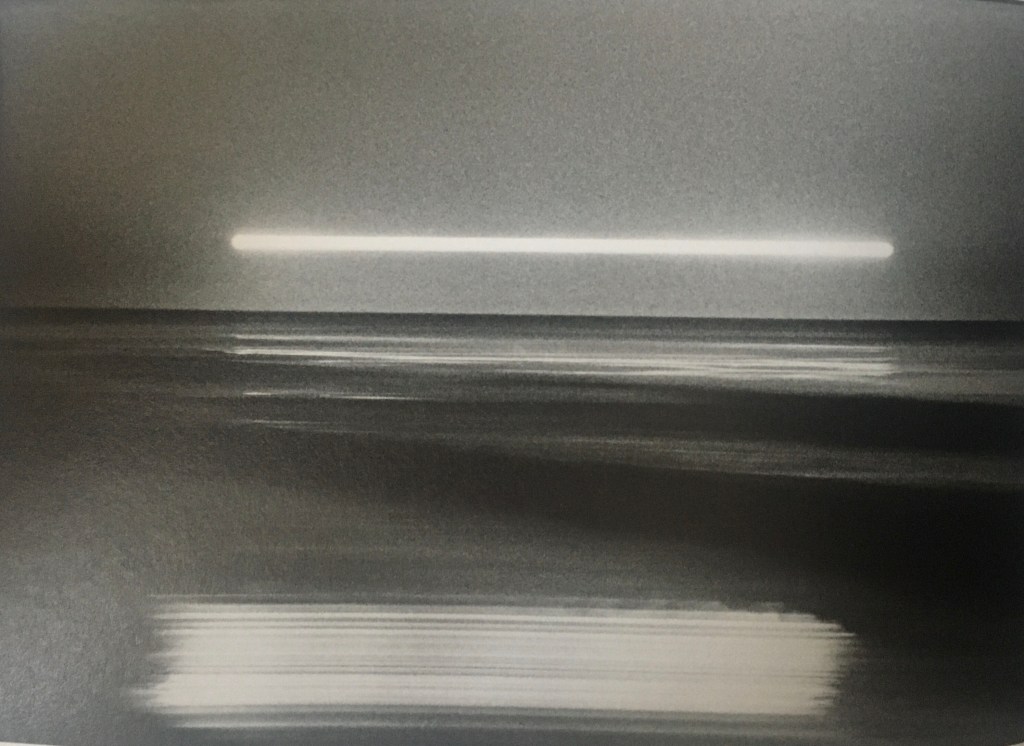

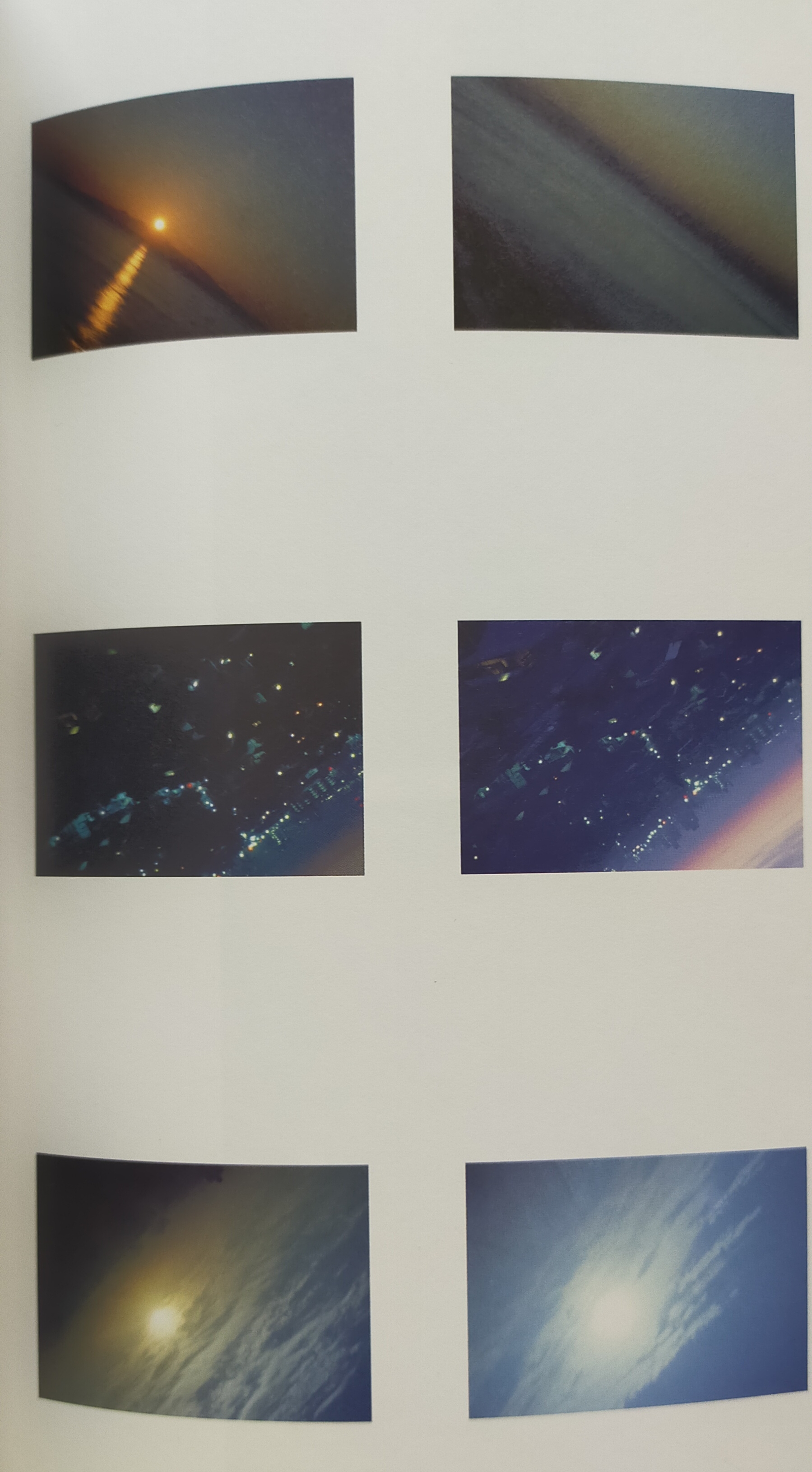

In addition to the screening, a series of panels, reproductions of Yamazaki’s photos discovered only after his death in 2017, were displayed in the Film Archive’s entrance hall.

I had already seen all of the films of the program years back, when the Image Forum Festival organized a bigger retrospective on the filmmaker. I also had the chance to write about Yamazaki’s masterpiece, Heliography (1979), and about his other experimental films he made during his career for this site. Moreover, a longer piece, where I draw connections between Heliography, Ogawa Pro’s Magino Village, and Matsumoto Toshio’s Ātman (1975), was recently published on Chute Film-Coop.

All of this to say that I went to Tokyo to revisit and rewatch Yamazaki’s films on a bigger screen, and possibly to experience them in a better quality. I had read, before attending the event, that the works would be screened digitally (ProRes), but I was a bit disappointed and sad to learn about the story of their condition and preservation.

Of the four, a print exists only of Heliography, prints or negatives of the other three, Vision Take 1, Observation, and Motion are regrettably lost. To my surprise, the digital copies screened at the event were made from VHS tapes (!) Yamazaki used to show in the university where he worked.

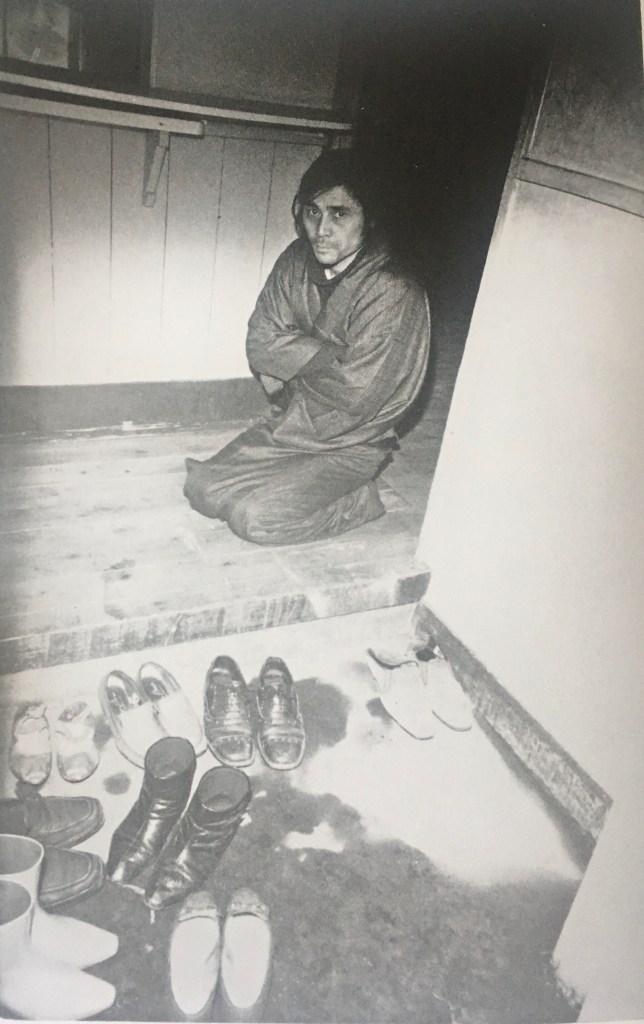

The after talk between Ishida Tetsurō, curator for the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, and organizer of Yamazaki’s last exhibition, and the aforementioned Hagiwara was casual, but interesting. Some anecdotes about Yamazaki’s life were shared, but most importantly for me, the two revealed some technical and conceptual aspects about Yamazaki’s filmmaking process.

Vision Take 1 (1973, 8mm, 4′) presents the viewer with the images of the sea, a constant in Yamazaki’s career, and a beach were a television stands. As soon as the landscape gets darker the TV set starts to light up with images of the same sea. This is probably the weakest of the bunch.

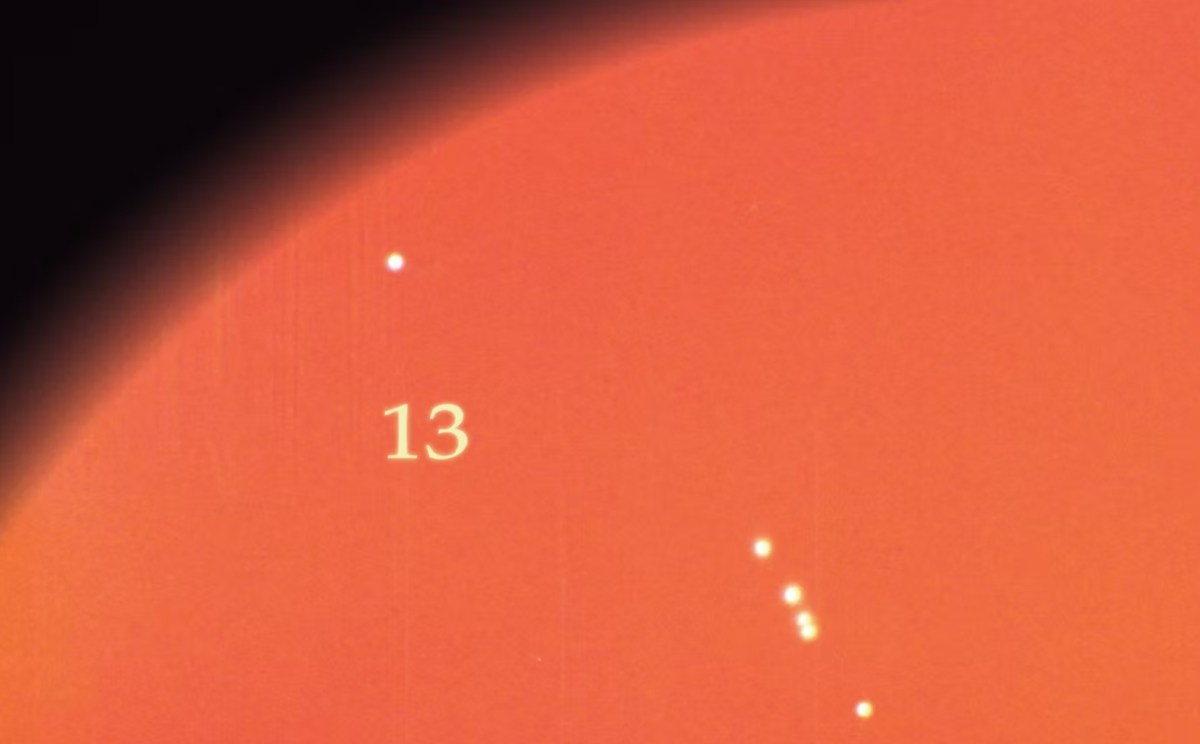

観測概念 Observation (1975, 16mm, 10′) is a film that starts with a fixed and very dark image of the filmmaker’s neighborhood. Slowly and gradually the scene, a couple of roofs, antennae and the sky, with students and a small truck passing on the street at the bottom of the frame, turns whiter and whiter. The screen turns dark again, and from the upper left side of the screen, accompanied by a pulsating sound, one after another, many small bright “suns” appear drawing an arc of sorts in the dark sky above a house. However, as emerged from the discussion, probably this is not the arc drawn by the Sun in the sky captured in time-lapse, like in Isobe Shinya’s 13 for instance, but something different that Yamazaki created to make it look like the real thing. “It’s fiction” as said by one of the two people on stage.

Yamazaki himself was interested in photography and filmmaking in that “the world created through media is different from what humans see with their eyes”. For instance, the two half of Heliography, first the Sun filmed in time-lapse setting over the sea, and then, after a couple of seconds of darkness, the star resurfacing from a city seen upside down, were shot from two very different locations. If we think about it from a technical point of view, it is quite obvious. However, in the film it feels like the point of view is conceptually the same.

The after talk revealed also how Motion (1980, 16mm, 10′) was made, or better, how the two speakers think it was made, because Yamazaki was quite secretive about his methodology. According to Hagiwara, the film was made by shooting in a shower with a strobe lens. Motion is a fascinating film, without sound, composed of a series of tiny specks of liquid reflecting light, superimposed with layers and layers of more lights, sometimes edited slowly, sometimes faster. Besides Heliography, this was the film that impressed me the most. For the way it is constructed, but also for its trance-inducing quality, it felt like an experiment by Makino Takashi.

The event was interesting, but I wish there were more films screened, because to understand what Yamazaki was trying to do with images and light, one needs to be immersed longer and deeper in his world, photographic or filmic (also, I’d really like to see Sakura, his film about “dark” cherry blossoms again).

You must be logged in to post a comment.