You can find this page on the menu above (I’ll post it here just to get more visibility):

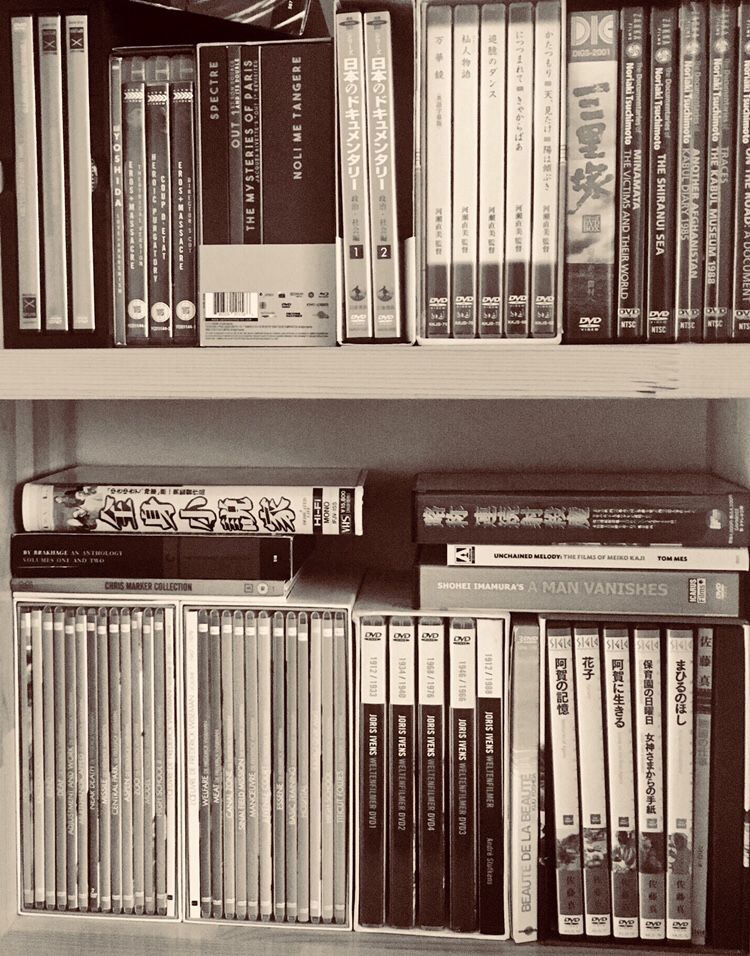

This is a page where I’ll try to list all the Southeast and East Asian documentaries that have been released on DVD or Blu-ray (no VHS o laser discs…yet), both those still available and those currently out of print. For now, since I’m writing in English, I’ve decided to include only the home releases subtitled in English, but there’s a lot out there with French subs (Yoshida Kijū or Wang Bing for instance)…

There are a couple of fundamental reasons why I’ve decided to embark in this task:

We can talk and write at length about a certain movie or a certain director, but if we don’t have the means to see the films in question, unless you have the money to attend all the festivals dedicated to documentary around the world, it’s like talking about ghosts, and sometimes absence creates myths…

Another reason, and maybe the more dear to me, is that in recent years I’ve become fascinated by the history and development of home video distribution and its circulation around the world.

Moreover, as always with lists, this catalogue might also work as a special way to discover new titles, authors and filmographies.

Since I’m based in Japan and the documentary scene here has been vibrant since the beginnings of cinema, most of the titles are Japanese. I’m sure there are many Chinese, Taiwanese or Filipino non-fiction movies subtitled and on DVD, if you know any of them, please let me know, you can leave a comment or contact me through Twitter (the column on the right).

The order is chronological, that is, old movies at the top and more recent ones at the bottom. I’ve used this format:

English title (if not available I’ve kept the original) – name of the director – year of production – format- DVD or BD company’s name – year of the home video release when available.

As usual, feel free to contribute, I’m also open to suggestions regarding the layout of the page (should I divide the list by country? by author, etc.)

You can navigate through the movies on the list I created on Letterboxd (although some titles are missing, but I’m slowly fixing it)

Yamamoto Senji kokubetsushiki / The Funeral of Yamamoto Senji (Proletarian Film League of Japan, 1929) DVD Rikka Press, in Prokino sakuhin-shū, 2013.

Yamasen Watamasa rōnōsō / Yamamoto Senji Watanabe Masanosuke Worker-Farmer Funeral (Proletarian Film League of Japan, 1929) DVD Rikka Press, in Prokino sakuhin-shū, 2013.

Tochi / The Land (Proletarian Film League of Japan, 1931) DVD Rikka Press, in Prokino sakuhin-shū, 2013.

Dai jyūsankai no Tōkyō Mē Dē / The Thirteen Tokyo May Day (Proletarian Film League of Japan, 1931) DVD Rikka Press, in Prokino sakuhin-shū, 2013.

Sports (Proletarian Film League of Japan, 1932) DVD Rikka Press, in Prokino sakuhin-shū, 2013.

Zensen / The Front Lines (Proletarian Film League of Japan, 1932) DVD Rikka Press, in Prokino sakuhin-shū, 2013.

Hokusai (Teshigahara Hiroshi, 1953) DVD Criterion Collection, in Three Films by Hiroshi Teshigahara, 2007.

Ikebana (Teshigahara Hiroshi, 1956) DVD Criterion Collection, in Three Films by Hiroshi Teshigahara, 2007.

Tokyo 1958 (Teshigahara Hiroshi, 1958) DVD Criterion Collection, in Three Films by Hiroshi Teshigahara, 2007.

The Weavers of Nishijin (Matsumoto Toshio, 1961) Blu-ray Cinelicious Pics, in Funeral Parade of Roses, 2017.

The Song of Stone (Matsumoto Toshio, 1963) Blu-ray Blu-ray Cinelicious Pics, in Funeral Parade of Roses, 2017.

Tokyo Olympiad (Ichikawa Kon, 1965)

a) DVD Criterion Collection, 2002.

b) DVD/Blu-ray in 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912–2012, Criterion Collection, 2017.

On The Road – A Document (Noriaki Tsuchimoto, 1964) DVD Zakka Films, 2011.

In Search of the Unreturned Soldiers in Malaysia (Imamura Shōhei, 1971) DVD Icarus Films, in A Man Vanishes, 2012.

In Search of the Unreturned Soldiers in Thailand (Imamura Shōhei, 1971) DVD Icarus Films, in A Man Vanishes, 2012.

Minamata: The Victims and Their World (Tsuchimoto Noriaki, 1971) DVD Zakka Films, 2011.

The Pirates of Bubuan (Imamura Shōhei, 1972) DVD Icarus Films, in A Man Vanishes, 2012.

Sapporo Winter Olympics (Shinoda Masahiro, 1972) DVD/Blu-ray in 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912–2012, Criterion Collection, 2017.

Goodbye CP (Hara Kazuo, 1972) DVD Facets, 2007.

Outlaw-Matsu Returns Home (Imamura Shōhei, 1973) DVD Icarus Films, in A Man Vanishes, 2012.

Extreme Private Eros – Live Song 1974 (Hara Kazuo, 1974) DVD Facets, 2007.

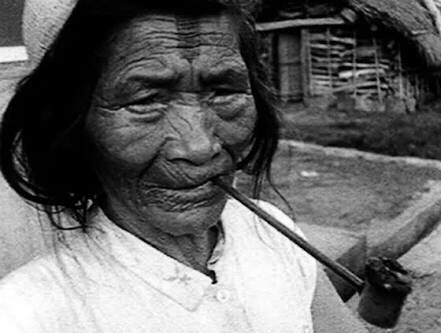

Karayuki-san, The Making of a Prostitute (Imamura Shōhei, 1975) DVD Icarus Films, in A Man Vanishes, 2012.

Kenji Mizoguchi: The Life Of A Film Director (Shindō Kaneto, 1975)

a) DVD Asmik Ace, 2001.

b) DVD/Blu-ray Criterion Collection, in Ugetsu, 2017.

The Shiranui Sea (Noriaki Tsuchimoto, 1975) DVD Zakka Films, 2011.

Turumba (Kidlat Tahimik, 1981) DVD Flower Films, 2005.

Antonio Gaudí (Teshigahara Hiroshi, 1984) DVD Criterion Collection, 2008.

The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches on (Hara Kazuo, 1987) DVD Facets, 2007.

Seoul 1988 (Lee Kwang-soo, 1989) DVD/Blu-ray in 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912–2012, Criterion Collection, 2017.

Hand in Hand (Im Kwon-taek, 1989) DVD/Blu-ray in 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912–2012, Criterion Collection, 2017.

Beyond All Barriers (Lee Ji-won, 1989) DVD/Blu-ray in 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912–2012, Criterion Collection, 2017.

Living on the River Agano (Satō Makoto, 1992) DVD Siglo, in Satō Makoto’s Complete Works box-set, 2008.

Embracing (Kawase Naomi, 1992) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, in Kawase Naomi Documentary DVD Box, 2008.

A Dedicated Life (Hara Kazuo, 1994) DVD Facets, 2007.

Katatsumori (Kawase Naomi, 1994) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, in Kawase Naomi Documentary DVD Box, 2008.

See Heaven (Kawase Naomi, 1995) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, in Kawase Naomi Documentary DVD Box, 2008.

Hi-Wa-Katabuki (Kawase Naomi, 1996) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, in Kawase Naomi Documentary DVD Box, 2008.

The Weald (Kawase Naomi, 1997) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, in Kawase Naomi Documentary DVD Box, 2008.

A (Mori Tatsuya, 1998)

a) DVD Maxam, 2003.

b) DVD Facets, 2006.

Artists in Wonderland (Satō Makoto, 1998)

a) DVD Siglo, in Satō Makoto’s Complete Works box-set, 2008.

b) DVD Zakka Films.

Mangekyo/Kaleidoscope (Kawase Naomi, 1999) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, in Kawase Naomi Documentary DVD Box, 2008.

Self and Others (Satō Makoto, 2000) DVD Siglo, in Satō Makoto’s Complete Works box-set, 2008.

Hanako (Satō Makoto, 2001) DVD Siglo, in Satō Makoto’s Complete Works box-set, 2008.

Sky, Wind, Fire, Water, Earth (Kawase Naomi, 2001) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, in Kawase Naomi Documentary DVD Box, 2008.

Letter from a Yellow Cherry Blossom (Kawase Naomi, 2002) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, in Kawase Naomi Documentary DVD Box, 2008.

A2 (Mori Tatsuya, 2002)

a)DVD Maxam, 2003.

b)DVD Facets, 2006.

Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (Wang Bing, 2003) DVD Tiger Releases.

S21 The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine (Rithy Panh, 2003) DVD First Run Features, 2005.

Another Afghanistan: Kabul Diary 1985 (Noriaki Tsuchimoto, 2003 ) DVD Zakka Films, 2011.

Traces: The Kabul Museum 1988 (Noriaki Tsuchimoto, 2003) DVD Zakka Films, 2011.

Mamories of Agano (Satō Makoto, 2004) DVD Siglo, in Satō Makoto’s Complete Works box-set, 2008.

Haruko (Nozawa Kazuyuki, 2004) DVD Fuji Television、2004.

Rokkasho Rhapsody (Kamanaka Hitomi, 2006) DVD Zakka Films.

Echoes from the Miike Mine (Kumagai Hiroko, 2006) DVD Zakka Films.

Bing’ai (Feng Yan, 2007) DVD Zakka Films.

Three Sisters (Wang Bing, 2007) DVD Icarus Films.

Campaign (Soda Kazuhiro, 2007) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, 2007.

Mapping the Future Nishinari (Tanaka Yukio, Yamada Tetsuo, 2007) DVD Zakka Films.

Mental (Soda Kazuhiro, 2008) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, 2010.

Flowers and Troops (Matsubayashi Yōju, 2009) DVD Zakka Films.

Breaking the Silence (Toshikuni Doi, 2009) DVD Zakka Films.

Holy Island (Hanabusa Aya, 2010) DVD Zakka Films.

The Everlasting Flame (dir. Gu Jun , 2010) DVD/Blu-ray in 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912–2012, Criterion Collection, 2017.

Ashes to Honey —Toward a Sustainable Future (Kamanaka Hitomi, 2010) DVD Zakka Films.

Peace (Soda Kazuhiro, 2010) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, 2012.

Barefoot Gen’s Hiroshima (Ishida Yuko, 2011) DVD Zakka Films.

Duch, Master of the Forges of Hell (Rithy Panh, 2011) DVD First Run Features, 2013.

Living the Silent Spring (Sakata Masako, 2011) DVD Zakka Films.

Fukushima: Memories of a Lost Landscape (Matsubayashi Yōju, 2012) DVD Zakka Films.

Theatre 1 & 2 (Soda Kazuhiro, 2012) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, 2013.

The Missing Picture (Rithy Panh, 2013)

a) Blu-ray New Wave Films, 2014.

b) DVD Strand Releasing, 2014.

c) DVD Edko Films, 2016.

Campaign 2 (Soda Kazuhiro, 2013) DVD Kinokuniya Shoten, 2015.

The Horses of Fukushima (Matsubayashi Yōju, 2013) DVD Zakka Films.

Flowers of Taipei – Taiwan New Cinema (Hsieh Chin Lin, 2014) DVD Edko Films, 2017.

The Last Geisha: Madame Minako (Yasuhara Makoto, 2014) DVD Zakka Films.

Ishibumi (Kore’eda Hirokazu, 2015) DVD/Blu-ray Vap, 2017.

Little Voices from Fukushima (Kamanaka Hitomi, 2015) DVD Zakka Films.

A Room of Her Own: Rei Naito and Light (Nakamura Yūko, 2015) DVD DIG, 2017.

We Shall Overcome (Mikami Chie, 2015) DVD Zakka Films.

Le Moulin (Huang Ya Li, 2016) Blu-ray/DVD Fisfisa Media, 2017.

Fake (Mori Tatsuya, 2016) DVD Happinet, 2016.

You must be logged in to post a comment.