After the special online edition of 2021 (the in-person event was canceled due to the pandemic), starting from today the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival is back in its regular format. For a week, October 5-12, the city in Northern Japan will be the capital of non-fiction cinema, with screenings, events, workshops, and meetings on and around the varied landscape of international documentary, with a special focus on Asia. If you want to have a look at the program, check the official page of the festival.

This will be my 5th edition (6th counting the online one), and the main focus for me will be following, as much as possible—but as usual everything changes during the festival—the huge retrospective on the works of Noda Shinkichi (1913-1993). A poet, filmmaker, film theorist, and an important figure to understand the different evolutions and developments of documentary filmmaking in the archipelago during the 20th century. Some of his works (industrial, science, and folklore films) are available on the NPO Science Film Museum‘s official homepage for free; or for rental, on the platform Ethnos Cinema.

この雪の下に Country Life Under Snow (1956), for instance, is a fascinating depiction of the harsh life in a rural area in Yamagata prefecture, while オリンピックを運ぶ Transporting the Olympics (1964), co-directed with Matsumoto Toshio, focuses on the logistics and the behind the scene of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. How things (boats, yachts, traffic cones, film reels, etc.) and animals (horses, pigeons) were transported from and to the capital.

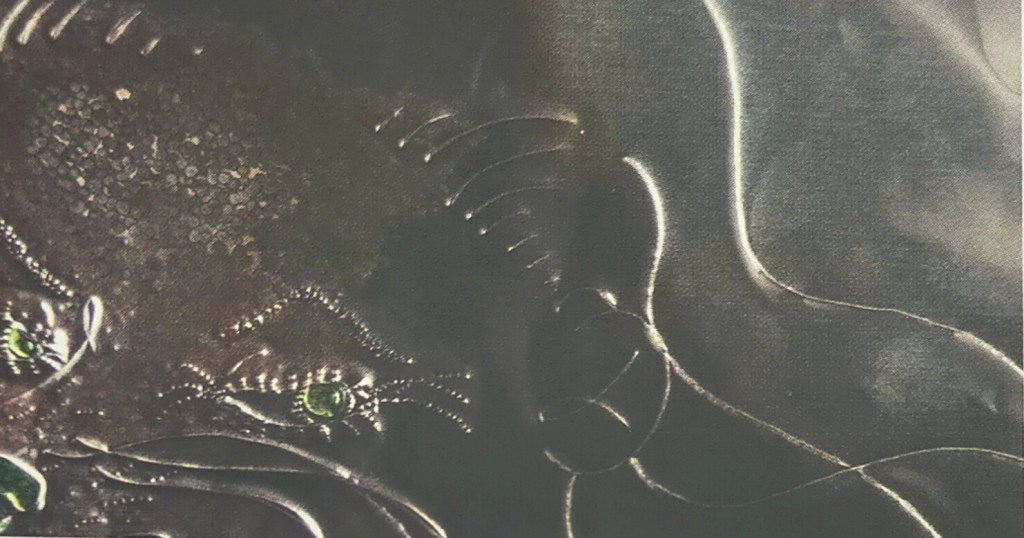

One of the most relatively known works by Noda is マリン・スノー-石油の起源-Marine Snow – The Origin of Oil, co-directed by Ōnuma Tetsurō, a celebrated science film produced by Tokyo Cinema, sponsored by Maruzen Oil Co., and filmed using Eastmancolor. The short film describes the vertiginous span of time (millennia) in which sea plankton, through decomposition, turns into natural gas and oil. Commissioned by an oil company, and thus partly celebrating the petroleum industry— directly only in its last 5 minutes though—Marine Snow remains a visually astounding piece of science film, flawed by its own design and origin, but astounding nonetheless.

You can watch here the version with an English narration (I prefer the Japanese one, for what it’s worth).

These films are just a fraction of what will be shown in Yamagata, in total the Noda’s retrospective includes 38 works, produced between 1941 and 1991. A Japanese/English flyer with summaries for each film is available here.

I really look forward to learn more about this towering figure in Japanese documentary, also because his contribution to the art of cinema does not stop with filmmaking, but it encompasses also books on the subject. One I’m particularly interested in is 日本ドキュメンタリー映画全史 Nihon dokyumentarii eigashi (1984), a history compiled by listing and analyzing the individuals involved in making documentary films in Japan, from the beginning of cinema to the mid-1980s. Having leafed through the volume, I could see names I had never heard before. I’m excited to discover more.

If I’m not mistaken, this retrospective in Yamagata originates from a special program organized in 2020 at the National Museum of Art in Osaka, an event that was unfortunately canceled because of the pandemic. One of the positive outcomes of this phantom retrospective was the publication online of a series of essays (in Japanese) exploring Noda’s filmmaking and his role in Japanese non-fiction cinema.

Naturally, many more works will be screened in Yamagata, the international competition, for instance, will present Self-Portrait: 47 KM 2020 (2023) by Zhang Mengqi, a friend of the festival who is bringing the newest entry of her ongoing film series shot in her hometown, and What About China? (2022) by theorist and filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha. One of my most anticipated works of the festival, the film was assembled using Hi8 video footage shot by the artist about 30 years ago.

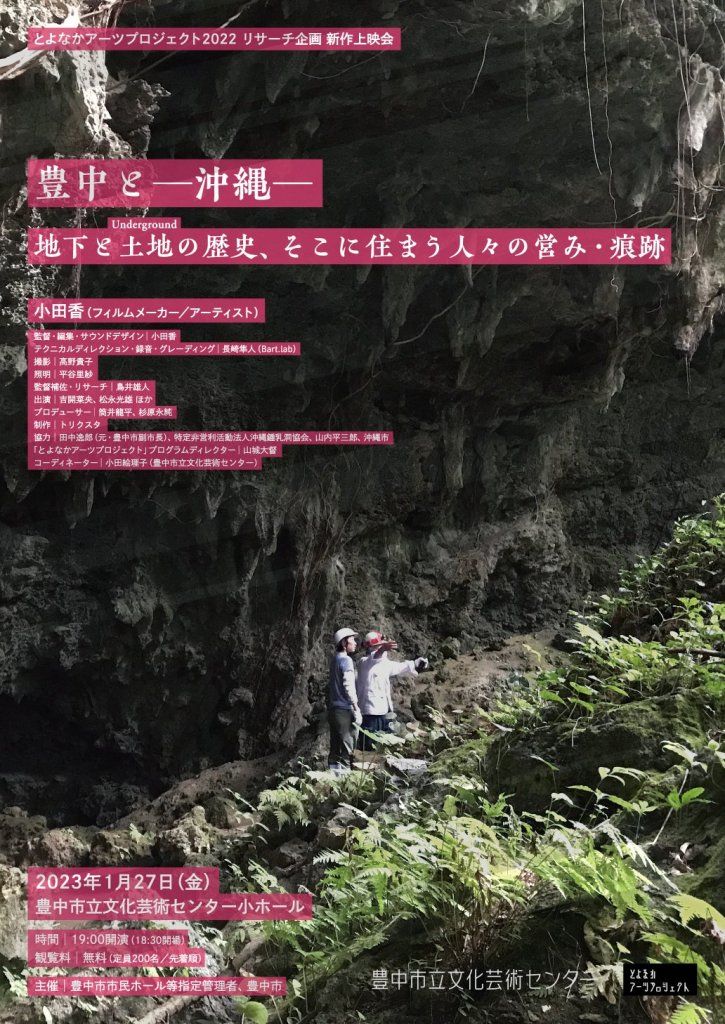

New Asian Currents is usually a section that does not disappoint, and in past editions, it was a chance for me to make some big discoveries. This year, one of the threads of the program seems to be a special attention towards Myanmar and the ongoing resistance to the current political situation in the country. Losing Ground (anonymous, 2023), Journey of a Bird (anonymous, 2021), and Above and Below the Ground (Emily Hong, 2023) are some of the titles dealing with the subject. Also in New Asian Currents, Gama by Oda Kaori (I’ve written about it here), and the always interesting Miko Revereza with Nowhere Near (2023).

Other programs of this year festival are Yamagata and Film, Cinema with Us 2023, Film Letter to the Future, Perspectives Japan, Double Shadows 3, and View People View Cities—The World of UNESCO Creative Cities.

Usually the most impactful viewings I had at the festival in the past—at any festival, to be honest—are those that came at me unexpected and that I discovered by chance or by word of mouth. Hopefully it will be the same this year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.