Last autumn (10 months ago!) I was lucky enough to attend a special screening event dedicated to the Japanese collective Nihon Documentary Union (NDU), at the Kobe Planet Film Archive. I’ve written elsewhere about NDU and the movies of Nunokawa Tetsurō, specifically about Asia is One (1973), and if you’d like to take a deeper and more academic dive into the subject, there’s this excellent essay by Alexander Zahlten on the Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema.

Titled From NDU to NDS, the program was organised by the archive’s director Yasui Yoshio and included the screening of To the Japs: South Korean A-Bomb Survivors Speak Out (NDU, 1971) followed by a short documentary/visual report by Kim Imman shot in 2008 (but I’m not really sure about the date), when Nunokawa Tetsurō and Kim himself went to Korea to meet the women portrayed more than 30 years before in the NDU’s movie. The last movie screened was Kim Imman’s Give Back Kama’s Rights! (2011), produced by NDS (Nakazaki-cho Documentary Space) and shot with the help of Nunokawa himself in Kamagasaki, Osaka’s largest dosshouse, a powerful example of video-activism/documentary of the new century. It is interesting to note that one of the members of NDS was Satō Leo, director of the surprisingly good Kamagasaki Cauldron War, one of the best movies of 2019 in my opinion.

The day ended with a short talk between Inoue Osamu, the only surviving member of NDU, Imman and a young Japanese scholar who specializes on NDU and 1960s/1970s Japanese cinema. The small theater was, with my surprise, packed, and extra chairs had to be added to fit everybody in.

One of the reasons for this relatively wide audience was that ー and I got a confirmation in the after talk, but more on this later ー the interest in the post war relations between Korea and Japan is still an open wound (at the moment I’m posting this report, July 2019, the tensions seem to have reached new hights).

This is the synopsis of the movie (from YIDFF) :

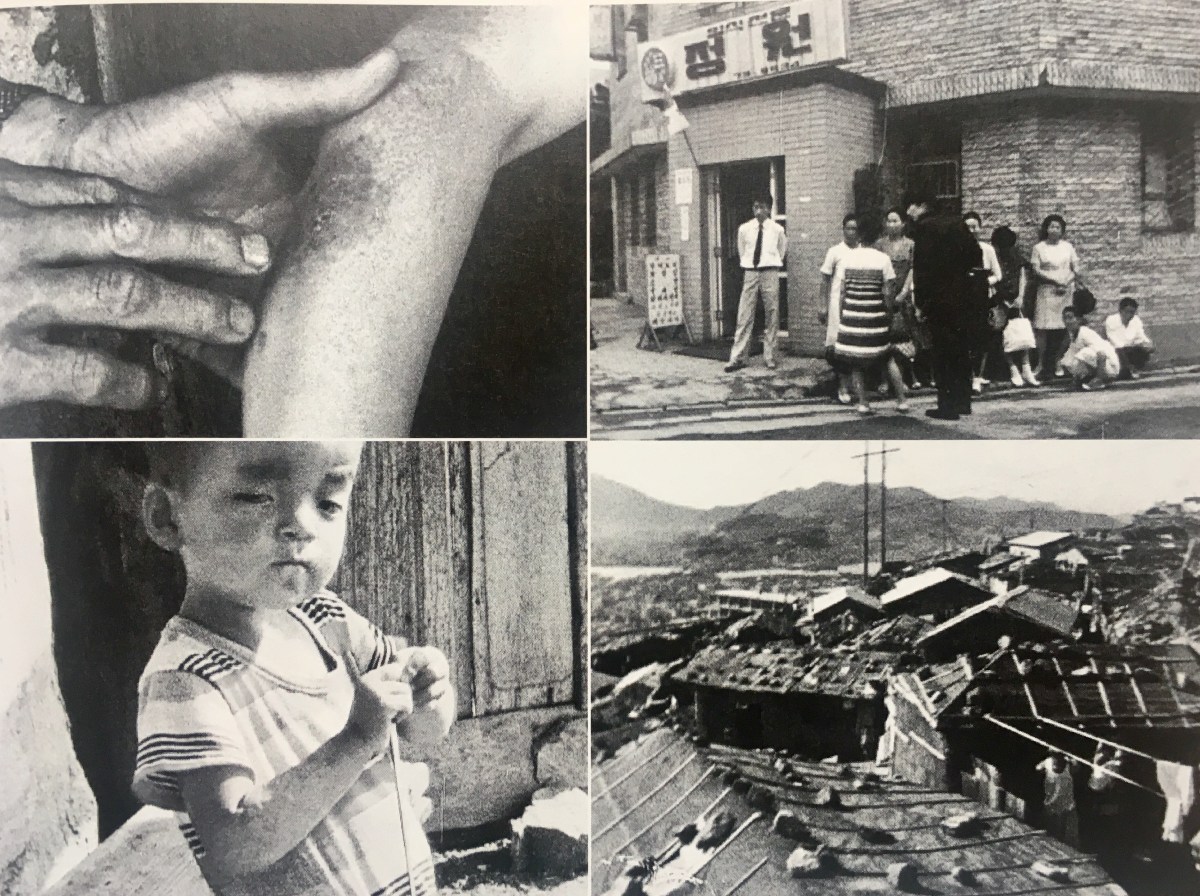

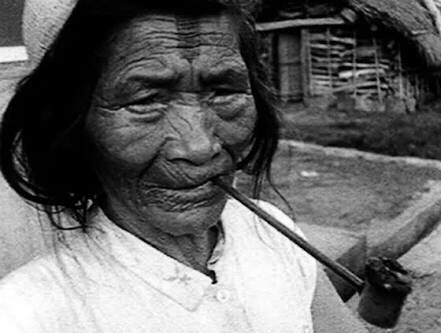

In 1971, while the Japanese prime minister Sato Eisaku was visiting South Korea to attend a party for President Park Chung-hee, a group of eight South Korean hibakusha(atomic bomb survivors) took a direct petition to the Japanese embassy. The South Korean hibakusha were detained by South Korean authorities for the duration of the prime minister’s visit. This film follows the lives of these eight people. That same year, Son Chin-tu, a hibakusha who had entered Japan illegally and was being held at the Omura Detention Center, filed his so-called “Hibakusha Certificate Lawsuit” demanding Japanese residency and medical treatment.

To the Jap was made in 1971, just after Motoshinkakarannu and before Asia is One (1973). The film opens with what looks to me like a parody of a TV commercial, but could just as easily be a real one, advertising the city of Busan and its tourist attractions, one of the main locations where the film was shot. From the first scenes, it’s clear that although the film is a documentary, it continues the arc started by Motoshinkakarannu, but differs from it in its style, reminding me more of the anarchic and pop finale of Onikko: A Record of the Struggle of Youth Laborers (1970), the first documentary made by the collective, when the film goes from black and white to colour and Nunokawa himself writes big red letters on a wall.

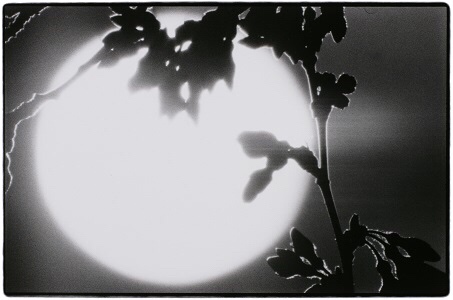

The vibrant colours of the early scenes are contrasted with the stark, almost blue quality of the black and white used to depict the women on the train as they travel to Seoul, and the more ‘traditional’ black and white used in some other parts of the film. This sense of formal non-linearity is accentuated and amplified by the off-sync audio – as in many of the collective’s other works, more a necessity than an aesthetic choice, I think – but also by the background noise of the city and the various and composite soundscapes through which the film is constructed. Once again, and this is a common trait that formally unites all the NDU’s films, especially Motoshinkakarannu and Asia is One, I would say, To the Japs proves that the documentaries made by the collective were first and foremost what I’d like to call a “cinema of chaos”, a complex and mosaic representation of reality, without seeking a resolution of conflicts and without searching for a clarity that isn’t there.

The after talk was too short and mainly focused on the absence of Japanese subtitles in some scenes in Imman’s short work, and on other language related problems in To the Japs, mainly why the women were called by their Japanese name and not by their Korean one. There are no doubts that these are very significant political topics worth discussing, however nothing was said on the formal elements of the film, and I think it was a missed opportunity.

In conclusion, To the Japs cemented my opinion of the importance of NDU and its place in the history of Asian cinema. Its insistence on liminal spaces and geographical thresholds continues to function today as a kind of cinematic alchemical ‘solution’, placing Japanese national identity in flux and pointing to a possible and desirable Caribbeanisation of the archipelago yet to come.

You must be logged in to post a comment.