Awaited every year with trepidation by cinephiles and the community of Japanese film-lovers, and a perfect occasion for discussing the state of the art in the archipelago and agree or disagree with it, last month the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo announced its 2017 Best Ten Lists . Launched in 1924 with only non-Japanese films, and from 1926 including Japanese movies as well, the poll includes, in its present form, four categories: Japanese movies, non-Japanese movies, bunka eiga and a section awarding individual prizes such as best director, best actor, best actress, best screenplay, etc.

You can check the results for all the categories here. Given the nature of this space, I want to focus my attention (with the slowness that characterizes this blog, apologies) on the bunka eiga list, that is to say, the best 10 Japanese documentaries released in 2017 according to Kinema Junpo (as far as I know only three have been released outside of Japan and thus have international titles):

1 人生フルーツ Life is Fruity

2 標的の島 風(かじ)かたか The Targeted Island: A Shield Against Storms

3 やさしくなあに 奈緒ちゃんと家族の35年

4 ウォーナーの謎のリスト

5 谺雄二 ハンセン病とともに生きる

6 沈黙 立ち上がる慰安婦 The Silence

7 米軍が最も恐れた男 その名は、カメジロー

8 笑う101歳×2 笹本恒子 むのたけじ

9 まなぶ 通信制中学 60年の空白を越えて

10 廻り神楽

With the term bunka eiga (cultural film), for a comprehensive analysis of the word and its usage in relation with other definitions, read here, the magazine awards non-fiction movies that explore social, cultural and political themes, often focusing more on the subjects tackled than on the formal aspects of the films themselves.

It is almost a fact that we’re living in a new golden age for documentaries, an era when every year, in theaters or on streaming platforms alike, there’s at least one film that push the boundaries of non-fiction cinema towards new territories. Unfortunately Japan, with all the exceptions of the case, seems to have stayed or have left behind. This is not the right place to discuss and deep dive into the reasons for this impasse, suffice to say that it is a problem affecting Japanese cinema in general and not only nonfiction movies.

That being said, it is nice to see at the top of the list Life is Fruity, a movie directed by Fushihara Kenshi and produced by Tokai TV, a production company based in Nagoya that in the last twenty years or so has been releasing a bunch of interesting and insightful documentaries. Again, all of them have quasi-TV aesthetics, nonetheless the topics explored and, in the best cases, the touch used, make them worth watching. Of the 21 documentaries produced by Tokai TV I’ve had the chance to watch five, among these my favorite is 青空どろぼう (Sky’s Thieves, 2010), a movie on the Yokkaichi Asthma, one of Japan’s four major diseases caused by pollution.

Life is Fruity tells the story of 90-years-old architect Shuichi Tsubata and his wife Hideko living in Aichi prefecture in a house surrounded by vegetables and fruits. Almost half a century ago Tsubata was asked to plan a new town in the area, but his idea of building houses that could coexist with woods and blend with the natural environment was rejected, and a project more in tune with the fast growing Japanese economy of the time was chosen. Tsubata left his job, purchased a piece of land and built his dream-house in a manner of his master, Czech-American architect Antonin Raymond.

You can see an English subtitled trailer by clicking on the Vimeo button:

Number two in the list is A targeted Village, the second documentary directed by Mikami Chie about the ongoing protests and resistance of Okinawa people against the American military presence and expansion in the island.

In 1983 director Ise Shinichi started to record the daily life of his 8-year-old niece Nao, a girl with intellectual disability who also suffers epilepsy, and her interaction with her family and society. After 12 years of shooting he edited the material into Nao-chan, a movie released in theaters in 1995, followed by 「ぴぐれっと」in 2002 and ありがとう 『奈緒ちゃん』自立への25 in 2006. やさしくなあに 奈緒ちゃんと家族の35年, number 3 in the Kinema Junpo list, is the fourth installment in this ongoing series and documents the ups and downs in the daily life of Nao and his family. I haven’t seen the movie yet, but it seems to perfectly continue the tradition of Japanese documentaries dealing with disability, from Tsuchimoto Noriaki to Yanagisawa Hisao (a retrospective of his works is happening now in Tokyo) and, in more recent years, Soda Kazuhiro with Mental.

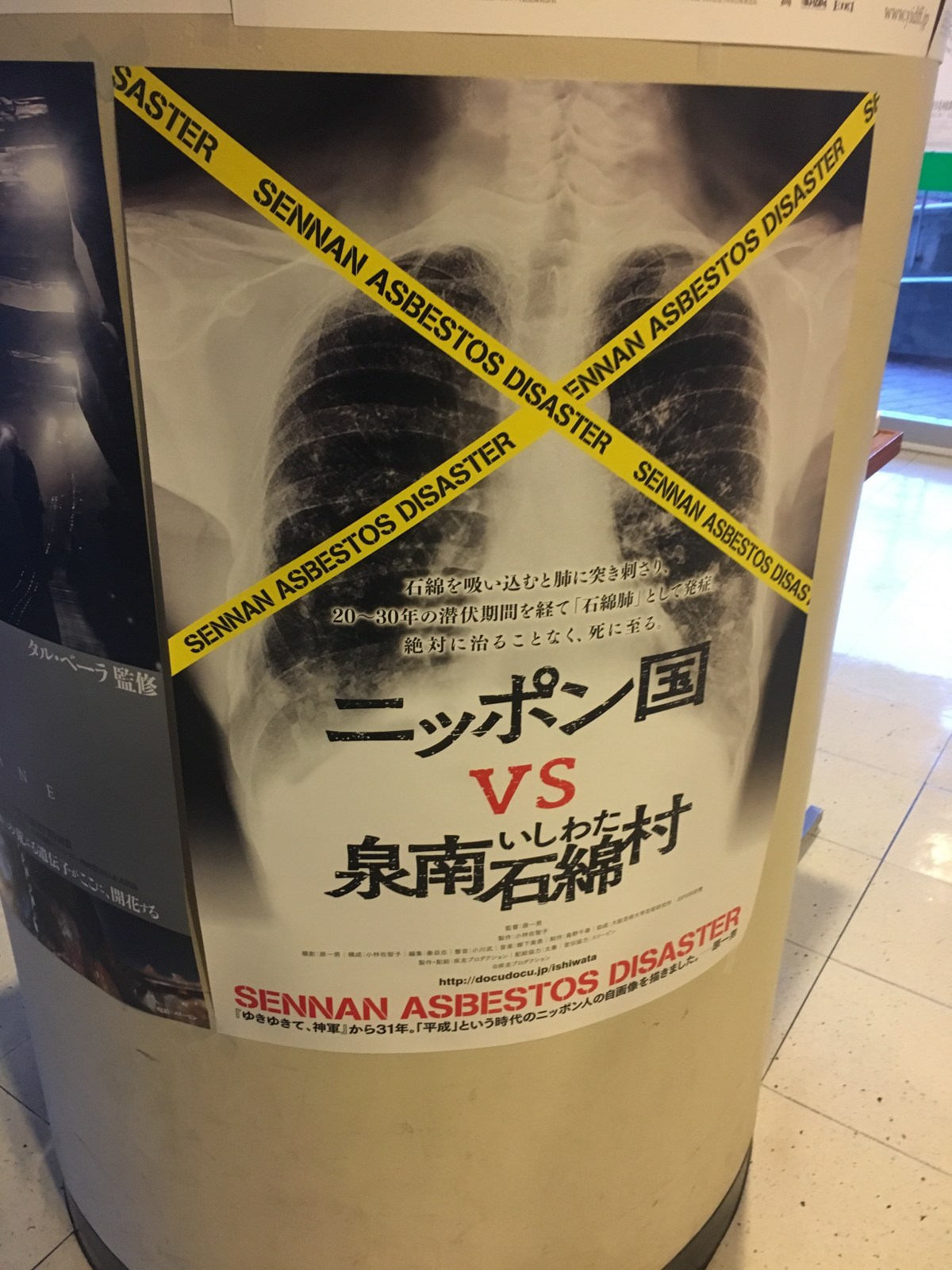

ウォーナーの謎のリスト is a documentary about American archeologist Langdon Warner and his list of culturally valuable Japanese sites that, allegedly, saved the most important temples and monuments from destruction during the American bombing of Japan in World War II. 谺雄二 ハンセン病とともに生きる tells the story of poet, activist and writer Kodama Yōji, who suffered from leprosy and fought against isolation and discrimination during his entire life, while with The Silence, second generation Japanese-Korean Park Soonam, records the struggle carried on by the victims of sexual slavery during the invasion of Korea by imperial Japan. In 米軍が最も恐れた男 その名は、カメジロー, his debut behind the camera, newscaster Sako Tadahiko explores the life of Senaga Kamejirō, an outspoken politician and communist who fought the American occupation of Okinawa until his death in 2001.

The list does not represent Japanese documentary landscape in its variety and complexity of course, by design the more experimental works are ruled out, nonetheless besides few titles, the films here selected don’t seem to hold any particular appeal to an international audience, again at the risk of becoming trite, it’s not because of the themes explored, but more because of what to me appears to be the lack of a distinctive style and vision.

You must be logged in to post a comment.