Fifth part of an ongoing series of translations dedicated to the writings of Haneda Sumiko (4th here, 3rd here, first and second here and here)

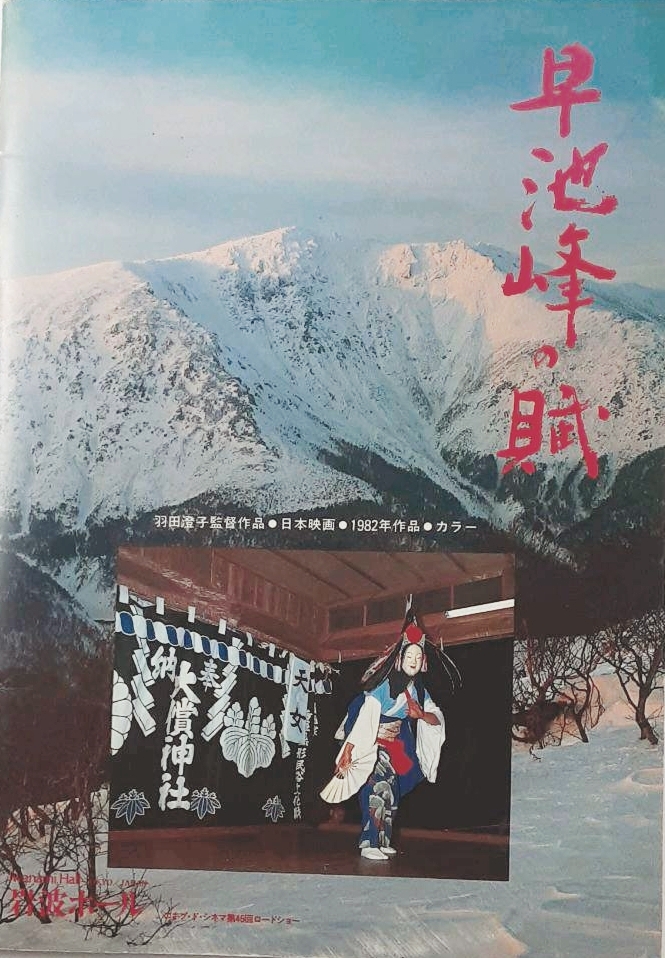

The short passages translated below—from 早池峰の賦 published in 1984—are very important and central to properly understand Ode to Mt. Hayachine, and more broadly, Haneda’s approach to documentary filmmaking. Just to provide a bit of background: Haneda discovered yamabushi kagura in 1964 in Tokyo, and the following year, the beauty of the performances and their connection with Tōhōku, when she visited Ōtsugunai, where she attended a kagura performed in an old magariya, an L-shaped farmhouse typical of the area. When she went back to the town in 1977, she noticed how the magariya and the culture associated with them were slowly disappearing from the scenery. She really wanted to start her documentary from a performance held in one of these old houses, an image that had stayed in her mind for decades, but instead she decided to go the opposite direction and started the movie by filming the demolition of one of these old farmhouses. It is interesting to note that, the first and shorter version of the documentary, 早池峰神楽の里 Hayachine kagura no sato, opens with kagura performed in the entrance of an old house, not a magariya, if I’m not wrong, and that the demolition scene is absent.

NOTE: This is by no means a professional translation, but I hope the readers can get the gist of it:

I first became aware of the Tōhoku region when I was in primary school, and read about a famine in the area in a children’s book. I think this was probably about the great famine of 1934. I had completely forgotten what it was about, but the tragic impression stayed with me for a long time. So when I think of the Tōhoku region, the first thing that comes to mind is a dark and impoverished image.

When I thought about making a movie about Hayachine kagura, I thought that Kagura is like a flower that blossoms and has its roots in the soil, that is, the harsh living conditions of the Tōhoku region. The true value of the flower cannot be understood unless it is depicted together with its soil. But how should this soil be expressed? In 1979, this was quite difficult.

When I first visited Ōtsugunai in 1965, the old farmhouses were still there, and the atmosphere of the old times was still strong. However, the rural landscape has now completely changed. Wide paved roads. Large concrete buildings. Houses just like in the city. Colourful tin roofs reflect the sunlight, and there is no longer any sense of history, poverty or darkness. I was at loss in front of this rural landscape.

The image of kagura I had in my mind was the one I saw during my first trip to Ōtsugunai [in 1965 when Haneda attended a kagura performed at the entrance of an old magariya, t/n]. I tried to find a place that somehow came close to that image, and in my mind I was constantly trying to recreate a scene like that. However, I soon began to feel that there was something wrong with obsessing over only old things. I realised that in order to depict the life of kagura, which has continued to live until today, even when the houses are new and the roofs are red, first of all it was important to accurately capture the present life of the farmers, and I also realised it would be a mistake to go too far in pursuing the perfect form, and thus to lose the vitality of the present. I was forced to change my methodology.

I thought that starting the shooting with the destruction of the magariya was quite symbolic. I filmed the demolition of the magariya as a symbol of the transfiguration of the rural areas in the Tōhoku region, but it also became the “demolition” of my own way of thinking. It doesn’t matter if the magariya are no more. It doesn’t matter if the roofs are blue or red. I wanted to make this work as an expression of the spirit of the farmers in Tōhoku, beyond what is visible to the eye, and as an expression of the ever-changing flow of history.

(pp 81-82)

You must be logged in to post a comment.