The 30th edition of the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival has ended more than a week ago. I was fortunate enough to be there, it was my fourth time, and for almost the entirety of the festival. What follows is a short report about things I’ve seen and my general impressions of the event. Please bear in mind that every film festival is experienced differently by each people attending it, depending on age, expectations, interests and the path each of us carve in the forest of movies screened.

As usual I didn’t see many of the films in competition, most of them are by big names, and, hopefully, will be screened in theaters o streamed on platforms in the near future. That being said, I really wanted to see Wang Bing’s Dead Souls, but its length deterred me, not the actual length in itself, but the fact that it would have eaten up a whole day of movies. Anyway I ended up not seeing it and I’m not sure I made the right decision, Dead Souls won the main prize, the Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize, and surprisingly to me, the citizen price as well. The other major award, the Special Jury Prize, was given to Indiana, Monrovia by Frederick Wiseman, a solid work, but not the best documentary by the American director, in my opinion, the main problem I had with the movie was the “fast” editing of certain scenes, the landscape scenes to be precise.

AM/NESIA: Forgotten “Archipelagos” of Oceania is the program I was most excited about, and it turned out I was right. The first work I saw at the festival was Lifeline of the Sea, a propaganda documentary made in 1933 with the support of the Navy Ministry of Imperial Japan, a film depicting the colonization and militarization of several islands in Oceania. It’s an extremely important document, almost ethnographic in its first part, when it depicts the various traditions and beliefs of the people inhabiting the islands, and overtly propagandist in the second part. It does that in such a bluntly way, it does not sweeten the pill so to speak, that it doesn’t hide the the fact that colonization is first and foremost about using other territories resources and exploiting people. A chillingly matter-of-fact documentary that found its perfect counterpart in the work screened soon after, Senso Daughter. Directed by Sakiguchi Yuko in 1990, the movie focuses on the legacy of the Japanese occupation of Papua New Guinea during the Second World War. A sad legacy that arises from rape, starvation and terror. It is an unflinching gaze at the horrors perpetuated by Japanese military towards women, the so called “comfort women”, in Papua New Guinea, told through interviews with ex-soldiers. While admitting the violence of war, almost all these veterans deny any violence or forced prostitution of women, on the other hand the director researches and presents us a very different reality when she interviews women who survived that period and painfully recollect those times. It is interesting to note that the documentary was released just a couple of years after Hara Kazuo’s The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, a movie that covers a different but related topic in the same area. Imamura Shohei also explored the topic of comfort women, sent from Japan in his film, in Karayuki-san, the Making of a Prostitute, a made-for-TV documentary aired in 1975.

A big surprise for me was to find out that Sakiguchi Yuko is the same person who directed from 2012 to 2108 Everyday is Alzheimer, a series of three personal documentaries about her mother’s dementia. A trilogy of films that had a relative success in the indie scene and in the mini-theater circuit.

AM/NESIA was a real discovery for me, unfortunately I saw only one more film, Kumu Hima (Dean Hamer, Joe Wilson, 2014) about a transgender person in contemporary Hawaii and how colonialism has affected and continues to affect people’s bodies as well, not only lands and territories. I bought the catalog, a beautiful book with which, hopefully, I will try to continue the exploration of the films produced in the continent. A forgotten cinema.

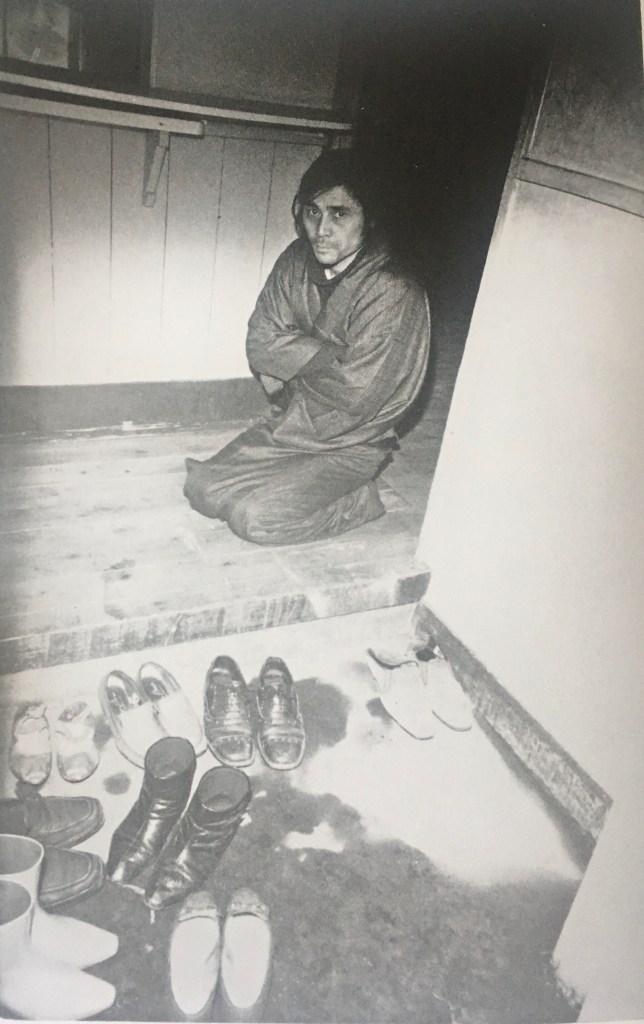

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The other program that I followed somehow closely was The Creative Treatment of Grierson in Wartime Japan. While some of the movies screened are “classics” of documentary cinema, Night Mail, Coal Face, or Housing Problems, the screenings were often packed, typhoon notwithstanding. When Night Mail was shown for instance, during the scenes when it is shown how the postal mail is delivered around the country without the train stopping, the audience was cheering and clapping enthusiastically like at a Marvel movie. I was really impressed, and this made me ponder about who these kind of festivals and screenings events are made for. They’re definitely not only for “experts” and professionals, and I was glad to notice that many people in the audience were young, well younger than me at least.

In the same section I saw Kobayashi Issa (1941), a film commissioned by the Nagano Prefectural Department of Tourism and directed by Kamei Fumio. I had high expectations for this, if you read this blog you know my love for Kamei, and this short movie completely blew me away. Told in a poetic and subtle way, using the haiku of poet Kobayashi Issa, the documentary goes against all the idyllic depiction of countryside and mountain life that one would expect from a work commissioned by such an institution. Instead Kamei sets his gaze on the poverty and on the conditions of the people living in the area, presenting also a witty deconstruction of a frame of thought that wants to consider countryside like an “other” or furusato, a ”home” where to go back, an origin. One scene in particular stayed with me because it summarizes the tone of the movie perfectly. An old man’s face in close-up (remember Fighting Soldiers?) is accompanied by a narration that solemnly says something like, I’m paraphrasing of course, “what is this man gazing at?”. When the camera zooms out and cut to the bigger picture though, we see him urinating against the mountain landscape. Definitely one of the best discoveries of the festival, still very fresh and relevant today, both for its thematic approach and its style.

I couldn’t see many of the documentaries screened in the New Asian Currents program, usually one of the most interesting of the festival, but I was able to catch a couple, among these, worth mentioning are Cenote (2019) by Oda Kaori and Temporary (2017) by Hsu Hui-ju. I had already seen Cenote in Nagoya a few month ago, but this was too good of a chance to re-watch it with better sound and on a bigger screen. The movie confirms Oda as one of the most original and interesting voices working in documentary today, if Aragane was a revelation (I wrote about it here, and interviewed her 4 or so years ago about the movie), her next project, Toward a Common Tenderness (2017), was conceptually different, but kept the aesthetic touch present in Aragane, adding to it a poetic and essayistic element. With this work Oda continues on the same path started with those two movies, the long take aesthetic is here translated underwater and intertwined with stories and legends told by the people of the area, Cenote(s) are natural sinkholes in Mexico, sources of water that in ancient Mayan civilization were said to connect the real world and the afterlife. If Aragane was a movie that revolved formally around darkness, slow movement and repetition, Cenote is a work about water and light. Images and soundscape are, as usual in Oda’s films, impressive and deeply interconnected, particularly in the scenes shot underwater inside the the sinkholes. Swimming in these Cenotes, the camera is enveloped in a reality that is perceived and created through water and light, going deep back the to womb of the earth, to the origin of life, as it were. When I saw the movie in Yamagata, I felt it worked less than the first time, maybe it was festival fatigue on my part, but I think the movie in its final part loses some of its power. Perhaps the words and faces of the Mexican people, shot in a beautiful and grainy 8mm, could have been used differently. That being said, the intensity I got from some of the scenes was almost overwhelming, Oda is aiming here higher than in her previous works, she’s trying to convey deeper and even religious meanings, and although not always successfully, there are moments when I felt that the underwater images (filmed with an iPhone!) combined with the sound/noise, reached almost a sort of spiritual materiality. I definitely need to re-watch it.

Temporary is an interesting documentary, albeit not completely successful, that experiments with reenactment “in the ruins of an abandoned factory, three temporary workers—a young man, an older man and an older woman—behave like a choreographed family, as they clean up, construct a table, and eat together.” It felt more like a draft for a future feature film than a proper work, and indeed director Hsu Hui-ju after the screening said that she’s now filming and making a new work about one of the men who appeared in the short movie. More interesting for me was to see another documentary by the same director (she had 3 movies in Yamagata!), Out of Place (2012), shown in the Cinema with Us program, this year dedicated to the depiction of disasters in Japanese and Taiwanese documentary. Out of Place It’s a personal documentary in which Hsu films the town of Xiaoling, after Typhoon Morakot completely swept it away in 2009. The grieving process of the people is intertwined with a quest for an identity by the director herself, her family and the people who lived in the village, most of them said to belong to the Pingpu ethnic minority. Besides the value of the documentary itself as a visual piece, there’s nothing really exceptional about it, the work excels at conveying a complex multi-layered picture of a group of people whose origins are very shifting and hazy. Instead of giving us simple solutions in easy and stereotypical sentences like “going back to our ancestral roots” or “find who we really are” and so on, Hsu expresses in images all her doubts about the importance of belonging to a certain group, and, this is my personal reading of it, in the end, the uselessness of finding a solid origin or a fixed identity. It was a very moving screening experience for me because, by pure chance, I sat next to the director and her young daughter, whose birth was filmed and shown on screen, and it was very sweet seeing them exchanging glances and smiles.

Not to insist too much on the subject, but this, after all, small movie, consolidated my opinion that contemporary documentary in Taiwan, or at least a certain portion of it, is in a really good and healthy stage, not only from a purely artistic point of view (read more here), but also as an example of an effervescent culture not afraid of exploring, and even moving away from, its multi-layered and complex origins.

In competition, besides the above-mentioned Monrovia, Indiana, I saw Memento Stella (2018) by Makino Takashi, an experimental movie in line with Makino’s previous works, a visual feast and experience like no others, and a film that I haven’t completely digested or absorbed yet. Interesting was also taking a glance at two other special programs, Rustle of Spring, Whiff of Gunpowder: Documentaries from Northeast India and Reality and Realism: Iran 60s–80s, where I had the chance to see for the first time A Simple Event (1973) by Sohrab Shahid Saless, passionately introduced by Amir Naderi, a beautiful discovery.

Among the festival’s satellite events that were organized in the city, I was lucky and brave enough, on the day the big typhoon hit Japan, to venture to the Yamagata University and attend a very special event. The use of Gentou (magic lanterns) in the social and grass-roots movements of the 1950s, with a special focus on the revolts and strikes in the Miike mine. The topic is so deep and rich of implications to understand the development of documentary in Japan, that I should write a separate article. The 1950s is a period often forgotten or neglected when discussing representation of social protests in postwar Japan, the priority is usually given, and in certain cases deservedly so, to the more cool or stylish production of the 1960s. For now, if you want to know more about Gentou, there are these two excellent pieces: On the Relationship between Documentary Films and Magic Lanterns in 1950s Japan by Toba Koji, and The Revival of “Gentou” (magic lantern, filmstrips, slides) in Showa Period Japan: Focusing on Its Developments in the Media of Post-war Social Movements by Washitani Hana

The festival was, as usual, an extremely exhausting but exciting experience, I would say it is a unique event, but I don’t really go to many other festival around the world. What I can certainly say is that it is a celebration of film culture, where everybody meets everybody else, directors, film professionals, cinema lovers, students or professors alike. As someone has rightly pointed out on-line, the YIDFF is more akin to a rock festival than a film festival. I couldn’t agree more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.